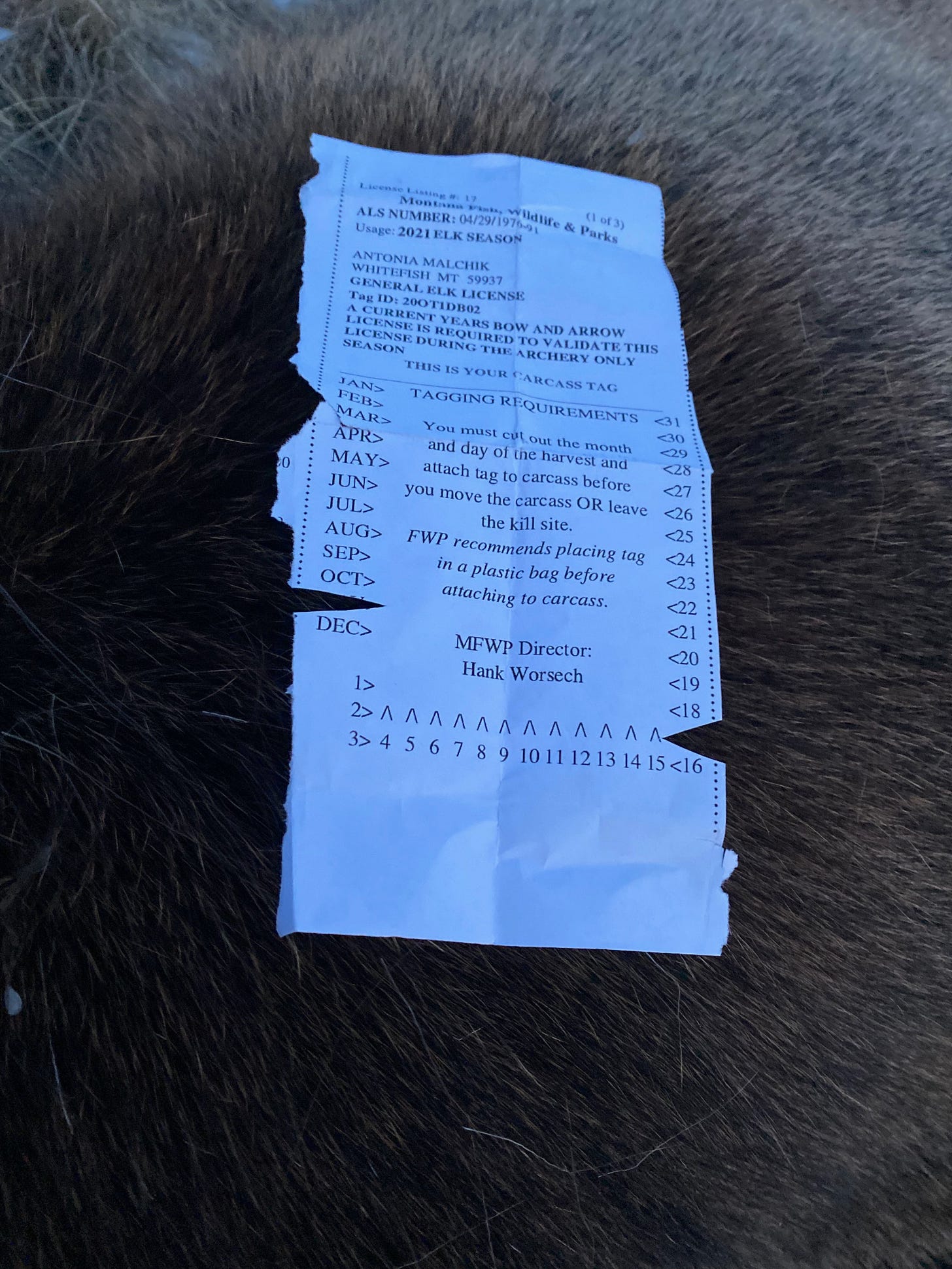

Last week, thanks to a birthday gift of time and a guide, I went elk hunting for the first time and clipped my tag at the end of a long, frigid day with biting winds. After nearly nine hours of following a herd across steep terrain, my legs felt stiff and incapable of one more step, my toes had long since lost all feeling, and my fingers only functioned thanks to the ample supply of hand warmers I’ve learned to pack when hunting.

It was gorgeous.

I fell in love with hunting the very first time I went out four years ago (my parents hunted throughout my childhood—venison was almost the only meat we had—but I was never taught so am what’s called an adult-onset hunter). The silence of the woods, the way that snow slides off the trees, the squirrels scolding and the ravens calling overhead. I once stood for at least twenty minutes watching a flock of chickadees twittering about between three trees. It was one of the most delightful things I’d ever seen.

I did things like that for three years, spending 30-40 hours alone in the woods each season in between work and mothering and the rest of life, before I ever successfully got an animal (and even that was essentially in a friend’s yard out of town), and never felt like a moment was wasted.

Hunting almost ruined hiking for me forever—I still love hiking but cannot escape the question, every time I step on a trail, “Why am I trying to go somewhere, and why so fast?” There is so much more to get to know off the trails, without a schedule or destination.

There’s also room to contemplate: your life, your day, your sorrows and joys, the meaning of it all, if there’s purpose to humanity, or a human. To sink into the realization that there is a tremendous amount going on in the world when humans aren’t looking. Even the little pockets of state-owned land near my home grant that feeling; within earshot of a highway I can step into a different world where things grow and communicate and interact to an unknown yet deeply familiar rhythm, a longer timeframe that I think we still recognize and crave somewhere in our DNA.

Gratitude comes easy at these moments. I certainly felt it elk hunting: to my family for making it possible, my sister for thinking of it in the first place, and our mutual friend for helping arrange it through a hunting outfitter she knew well. To the guides for bearing with me patiently all day and the one who brought me tequila at the end of the day “to see if you were still alive;” and my friend who taught me to both shoot and hunt and is always ready for a conversation about ethics. To that friend and my brother-in-law for spending a day later in the week helping me prepare the elk for the freezer.

Deepest of all to the animal herself, the land that supported her and her community; to the Blackfeet for whom that land was home and storied long before white ranchers claimed it as theirs. More complicated gratitude to the rancher himself for allowing hunting on that land.

That last gratitude is a struggle, not for the gratitude itself, but for the shape of it; the thanks I’m able to give the landowner is a totally different thing from what I feel for the elk whose life I took and the land that supported her and the people who truly belong to that land. They’re not the same feeling but the word wraps around both. I wonder what kind of belonging the rancher feels with and for the land that our legal system says is his? I hope it’s something like a partnership, that he finds connection in it.

It’s all these things that brought me to a strong position of public land advocacy several years ago. It’s why I spent this last year doing advocacy training through Artemis Sportswomen, and why I’ve written about the freedom gifted by public lands—how they’re the holdout legacy against the enclosure of the commons that began some 800 years ago, a taking, a theft, that has never ended. How all of our more abstract freedoms were formed and shaped in forest courts that determined people’s ability to sustain themselves from the land they lived with. How we have to grapple with the fact that these North American public lands, which give us freedom, were stolen in the first place and how we face that fact going forward.

Advocates of all stripes, as Chris La Tray wrote about in his newsletter last week, like to say that private property is bedrock. But private property is simply a story that we tell ourselves, a story that’s been around so long that many people seem to think it’s a law of nature, like gravity. It has taken many different forms over the centuries and will continue to do so—we could have a Right to Roam, like Scotland, or we could double down on No Trespassing signs and armed enforcement of boundaries. Either is a story we could choose. What’s bedrock is the land itself. What we think of as higher freedoms, even what we think of as citizenship, are in fact deeply grounded.

It’s also why I try to work in my own community to find ways to make it livable and affordable for all, why I give my time to committees and city council meetings and our truly wretched state legislature. I want where I live to be a place that remains a delight to reside in and a place where normal people can afford to do so.

That last is a struggle that right now we’re on the badly losing end of, but it’s one that I believe everyone who has the ability and time should devote themselves to working on, wherever they live, and even if they’d rather, like me, just spend their time out in the woods away from these more intractable problems. Tracking elk was incredibly challenging, but it’s nothing compared to persuading people not to widen a highway, or figuring out how to actually make in-town housing affordable in ways that don’t just depend on crumbs from developers. If we can’t make our own communities good places to live, then we’ll lose everything else that matters to us, including the public lands that provide us with clean air and water, solace and mental rest, and the basic ability to offset a little of our hard-earned income with food gathered in other ways, not to mention what they provide the rest of non-human life.

The elk I brought home was on private land, a place of nearly indescribable beauty where the Sweetgrass Hills rise steep and lopsidedly timbered and you can look north to Canada just three miles away, or west to the Rocky Mountain Front, a view that never ceases to be magical. My feet strained to stay stable on the steep, slippery, snow-covered hillsides as I thought about private land and public access and “please don’t let me drop my rifle.” The next day, driving home, it came to me that the stories that particular land holds, its own stories, are far larger and deeper even than the first glimmers of human ownership some seven or eight thousand years ago.

A story I might never get to know, but if I interacted with it in any way on that day I hope it felt my gratitude.

Sunset over the Rocky Mountain Front.

The hunting part is foreign to me -- something that I'd never think about nor truly understand, but you've spun gold here, and I appreciate it.

This is beautiful, Nia. I received a hunting rifle years ago determined that, if I am going to eat meat, I need to kill it myself. I've never aimed it at a living thing. Now as I get older, and my friends who do hunt tell crazy stories every year of growing crowds at the places they hunt, I begin to think I never will. It is just another of the deep sadnesses thrown onto the heap of ones I carry around.

Also, thank you for not posting the obligatory, "Here is me with my dead animal" photo. I hate those.