“All things

are peaceful

and kind

on the other planet

beyond this Earth.

But still I hesitate

to go alone.”

—from “Another Planet,” by Dunya Mikhail

Last weekend, I went for a walk in the woods with some friends on a trail none of us had been on before. Nothing spectacular. I couldn’t even seem to take a photo that demonstrated more than that the area looked to have been logged or thinned long enough ago that you couldn’t see much evidence of it. While we walked I thought about how the clearings around us would be populated by little larch trees in about twenty years. And though I won’t see them for decades, the thought made me smile because there is nothing like watching sunlight flicker across a wide, quiet grove of toddler larches turning yellow, while a raven calls overhead.

1-minute audio from a different walk along the local river. Red-winged blackbirds, and I could have sworn I heard a Swainson’s thrush in there? Maybe you knowledgable-about-birds people will know.

I didn’t have time for a walk. Really didn’t have time. I had a bunch of work things due and a volunteer commitment that was looming over me like a small, burning galaxy that wants me to feel the immensity of its mass. I’d been trying to keep panic attacks at bay for three days straight. Unsuccessfully. Which meant that, while I didn’t have time for a long walk, I also didn’t have time to not go on a long walk when it was offered.

In the midst of it all was Substack’s hard piling into some kind of social media engagement, which you’ve probably read about elsewhere so I won’t go into it, but it’s aggravating to keep digging through my settings to figure out how to turn off notifications that simply refuse to be turned off. It’s like one of my most regular recurring dreams, where I’m waiting tables and getting people’s orders wrong or trying to handle too many water glasses; or the one where there’s a huge house full of clutter that I have to somehow figure out how to clean up. (One of my many household chores growing up was dusting, which is probably reflected in my low tolerance for clutter wherever I live.)

There are all sorts of things to be annoyed at with this, but as with so many other things it comes down to lack of control over our choices. I hate that, for anyone. Notifications online aren’t on par with breathing polluted air because you couldn’t shut down a medical waste facility or someone decided to put a 16-lane freeway in front of your school; or finding yourself without a home because an absentee landlord bought your apartment building and jacked up your rent; but it probably comes from a similar rootstock, which is that someone with more power decided that they get to make your decisions for you.

There are a lot of things I’m thinking about with Substack and what kinds of choices people do or don’t have control over because some tech-bro dude decided they know what’s best for all of us. Even as I type that I realize that I’m repeating things I’ve said many times before, like in this post about why I originally left Twitter years ago and lack of choice (content warning for anti-Semitism). If you want to pay for this newsletter and would rather bypass giving Substack itself money, or if you just want to write a letter for other reasons, a mailing address is always on my website. It won’t help with the notifications, and I’m not sure leaving the platform to print and mail out essays is a viable option, nor would that disentangle anyone from the wider systems of injustices we’re forced to participate in. I don’t have any answers and don’t really trust anyone who says they do. But if you want to talk about it, I’ll willingly listen. There’s something insidious about others’ priorities being intentionally crashed into our time and attention from every angle possible, though the world is full of choices being imposed on those who have little say.

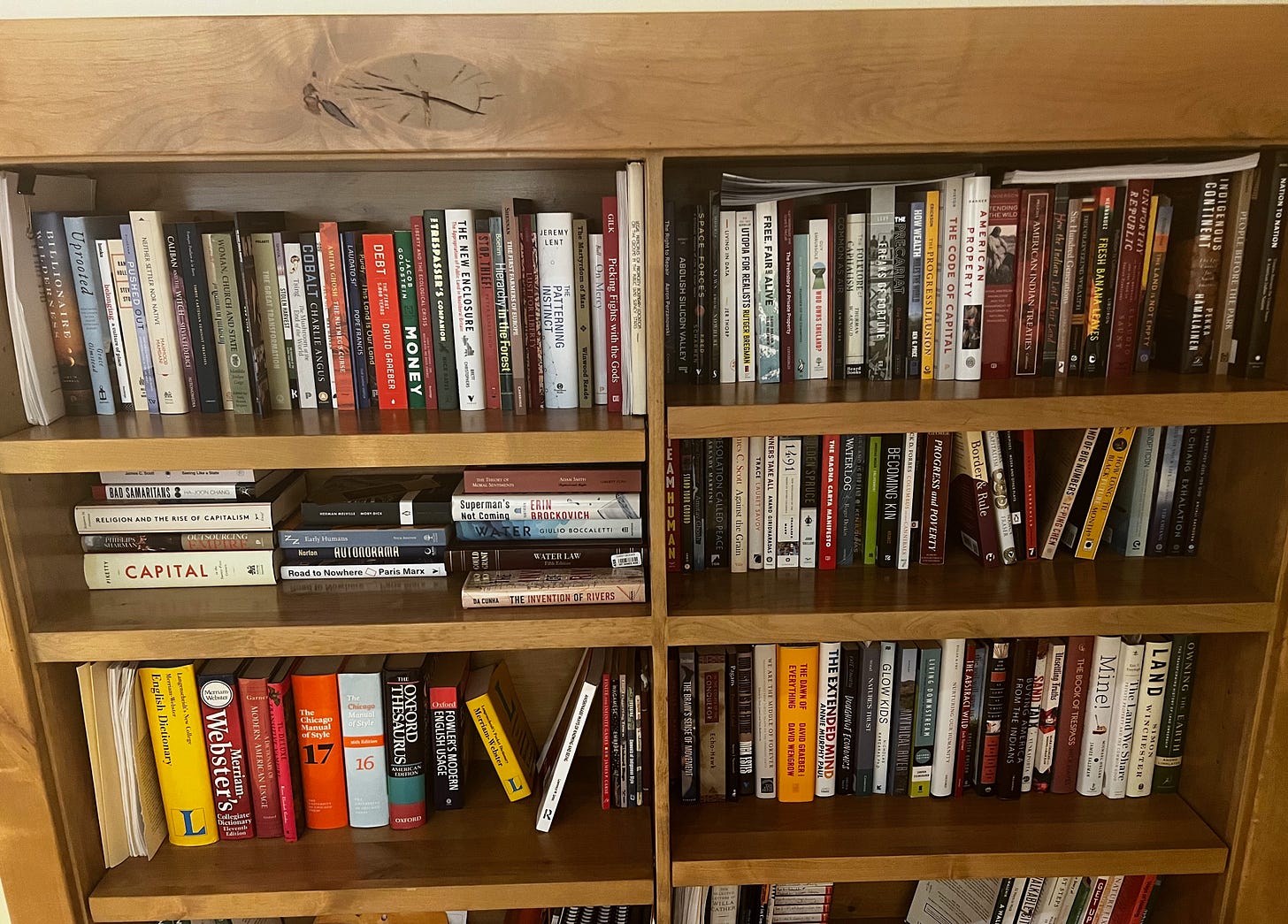

Of the eighty ownership-related books remaining in my to-read pile, there are only sixteen by women. Something that became apparent early on in this project is that almost all books on property are written by men, almost all of them white men, and almost all of them increasingly irritating. Stuart Banner’s American Property in particular is one I’ve started three times and returned to the shelf within an hour.

Unless the writing is explicitly anti-capitalist, it’s also particularly noticeable that the tone of the book carries a kind of March of Progress whiff about it. Even Andro Linklater’s Owning the Earth, which I really like, has this flavor. As in: The atrocities and losses that can be laid at the feet of this worldview and its enforcement are regrettable, but such is the way of progress and look at what we get in return.

To which my response is always, “Who is the ‘we’ you’re referring to here?”

When it comes to “progress,” the question that sits with me is: who is making sacrifices for others’ comfort or ease or security, and did they have a choice in the matter? Every time I turn on my car, I think of it as participating in a war on Bangladesh, which might seem extreme, but that land isn’t choosing to sink under sea level rise on its own. And my dependence on an internal combustion engine isn’t something I have much of a choice about in North American society. I don’t drive it every day, but even that choice is a luxury born of living in a walkable community whose affordability has rapidly become nonexistent.

There are very few mainstream books on property and ownership that spend any time facing these kinds of realities; those that do ask readers to imagine a completely different paradigm than the one we’re generally told is fixed and inevitable.

I’m slowly making my way through Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons. Ostrom was an economist who won the Nobel Prize in 2009 for her research on commons-based shared resource management systems, fisheries being a prime example. Her book is meticulously researched and referenced and so tedious that I can barely get through a page at a time. I’ve read a lot of painfully dull books that grew out of Ph.D. theses, but it’s been a long time since I’ve read one that felt exactly like a Ph.D. thesis. It’s important work, though, and she’s probably not to be blamed for trying to make it as scrupulously academic as possible. Considering how badly the dominant culture wants to believe that private, individual ownership (or, as Ostrom also addressed, complete state control) is the only safe way to structure a society, anyone countering that view probably feels that their case has to be almost unassailable. Even I feel that pressure, which is probably why I’m reading too many books on the subject.

A lot of those books end up referring to one another. In the current case, it’s Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse, which I finally removed from the shelf and sat down with yesterday and read in a few hours because it’s not boring, and it also has a long section talking about Ostrom’s work. It’s not exactly the book I expected. It seems to have grown out of The Great Derangement, which in the end I like more. Both of them are about narrative, which is—I think—an overlooked element in why the solutions to so many of the massive problems our world faces have trouble gaining traction. The narratives that get promoted and believed are those that undergird the dominant culture that benefits from them.

Ghosh’s contention is not only that writers and artists of all kinds need to show some responsibility to narrative, and to writing ones that counter the dominant culture beliefs—that was in essence also what The Great Derangement was about—but that part of what the dominant narrative has buried is Earth’s and all its entities’ abilities to tell their own narratives. Use their own voices.

The question is, who among us has the time and attention, much less uses the time and attention, to listen? I don’t know that I’ll ever truly understand these voices, so it feel more important to listen to people who can. Which is probably why I keep putting Stuart Banner back on the shelf. His voice is everywhere, even if it’s not his. That story is dinned into us all the time. I want to hear other ones.

One of the minor volunteer things I do is run a school board candidate forum every year. This was my fifth year doing it, and the regular moderator who also helps me with a bit of organizing had too much going on to participate. I’ve been overwhelmed with other commitments and got a late start on the organizing and frankly just felt a mess about the whole thing. Organizing events of any kind isn’t something I’m good at and I also don’t enjoy it. I can barely manage to make my kids’ birthdays feel special. But there was nobody else to do it. And by “nobody else” I don’t mean “Nobody can do this but me because I’m unique;” I mean that I’d spent the previous three weeks asking literally anyone I could think of if they could take it over and nobody had said yes and it was too late to cancel it.

I explained this all to my three friends on our long walk, and in return one of them offered to make the flyers, which is always one of my sticking points (I also am not good at designing things). My friends then pointed out ways in which I made the forum harder than it needed to be by trying to accommodate everyone’s time restrictions.

My one friend’s offer, and talking through it all, helped unwind the anxiety and proved to me once again that a walk is never a wrong answer. It made the forum feel manageable. I went home, scheduled the Zoom webinar because I couldn’t find a night that everyone could participate in person, sent the old flyer to my friend to update, emailed the candidates, did all the fiddly things I usually have to do to get this thing ready, and felt somewhat more prepared to handle what was going to be a very busy week.

The next day, I came down with food poisoning and was in bed for two days straight. Having, for some reason, repetitive dreams about waiting tables and cleaning cluttered houses.

The night of the forum saw me feebly crawl into clothes and apologize to candidates and attendees for my brain losing the plot as the forum meandered on. At one point I forgot everyone’s names and forgot that Zoom had their names displayed right in front of me. These are people I’ve known for years, mind you. It wasn’t like we’d just met.

Having that long walk in the woods—in what I hope is a baby larch nursery—behind me and a few good friends at my back made me mind all that less. (Kind of. Food poisoning sucks. Never recommended.)

It hasn’t given me a good answer to the tangledness of online life. I’m not sure it ever will except that the more the digital world is pressed upon me, the more offline and outside I go. All I know is that I want all of us to have choices about these things. I also want us to be aware that our choices affect others, especially others we might never see or know about, and also to remember that many of the choices we hold ourselves responsible for are not necessarily ones we have a lot of control over. But the digital world is still new, and the more we insist on having real choices now, the more will be available to people in the future. (How to achieve this I have no idea but I think we have a responsibility to try.)

I chose to open a window today while I worked, now that it’s finally not snowing and freezing, and listen to the robins and chickadees instead of music, and to space out gazing at the near-bursting buds on the caragana bush, and to wonder if I should get my seed potatoes going or if we’ll have another blast of winter. And if I’m doing the right things, and what parts of my life I’ve wasted, and if I have time for a walk before making dinner, and how much choice I, or you, have in any of it, and what our responsibilities are to ourselves, our communities, and the world.

The choices, the responsibilities, the lack of both and awareness of both—they lace in and out of one another in a world whose narratives and self-perceptions have been knotted up and obscured for a very long time. Maybe one of the best things we can do, or if not the best at least a first thing, is to go for a walk, try to find some clarity, and listen for stories that might be trying to reach us through other mediums. Like larches, or birdsong, or friends, or a sky that wants us to know all of its moods.

Speaking of the book-in-progress, No Trespassing, I am currently revising the Introduction and will be sending it to beta readers in May, hoping to share it here with all of you in June. The first chapter, on land ownership, will be my main project while at the Dear Butte residency June 5-15. The overview of that book project is here.

Some stuff to read (r) or listen (l) to:

(r) Vivek V. Venkataraman writing in Aeon with one of the more thoughtful essays on work, leisure, and being a hunter-gatherer that I’ve read in a long time: “Today, many of us are doing the wrong kind of work, one that rejects sociality, craft and meaning, turning people into machines. In contrast, the physical, mental and social are inextricably linked in hunter-gatherer work.”

(l) A fun if daunting interview on Building Local Power about managing rats in cities that’s probably best described by its title: “Rats Aren’t the Problem in Cities. We Are.”

(l) From Future Natures, a conversation with agronomist Almendra Cremaschi on open-source seeds in Argentina and the implications of enclosing the seed commons: “The development of the terminator trait is a metaphor for what patents do to knowledge.” (The sound quality of this one is a bit in and out. I had to use headphones to catch it all.)

(l) On Frontiers of Commoning, a conversation with the authors of Co-Cities about building on Elinor Ostrom’s work to apply commons thinking to cities, with their mixed public and private ownerships and conflicting jurisdictions.

(l) Thanks to Jake for sending me this episode of How to Fix the Internet (from EFF, the Electronic Frontier Foundation) with science fiction writer Annalee Newitz, who really got to the heart of what I think science fiction can do for our understanding of the present: “Story gives us the access to seeing how a struggle that might last generations plays out over time.”

(r) Black farmers in Tennessee are fighting to be fairly compensated for land taken via eminent domain for a Ford plant: “For the sake of his four children and grandchildren, he welcomes development to the area. But, like the other Black families who spoke to the Tennessee Lookout about eminent domain lawsuits filed against them, Sanderlin drew a direct line from the state’s current efforts to take his land to the struggles in every preceding generation of his family to hold onto what they owned. ‘It’s not the first time we’ve had to fight,’ Sanderlin said.” (It can never be said enough that even private ownership of land will not provide security of it.)

(l) Otters and beaver, plastic waste, wool, and re-envisioning urban community land on the Scotland Outdoors podcast. (The portion about turning an old railway line into a bike and pedestrian path starts at about 12 minutes in.)

(r) “The Difference Between Love and Time,” a science fiction short story by Catherynne M. Valente, was just pure fun: “I took the continuum to that little Eritrean restaurant down on Oak. It ordered tsebhi derho with extra injera and ate like food had only just been invented, which, given the nature of this story, I feel I should stress it had not. I just had the yellow lentil soup. The space/time continuum cried in my arms. It thought it had lost track of me. I didn’t answer its text messages. If it was a commercial cereal brand it would be Cap’n Crunch Oops All Genders.”

I am too tired this evening to leave a very thoughtful comment (a long telephone conversation with one of my daughters that lasted into the wee hours of the morning and was worth every moment); but if I may, here are a few items:

The kind of progress that Linklater seems to celebrate (or at least apologize for), is, among other things: a progress that presupposes human superiority, human happiness as the greatest good in the cosmos, human ownership (dominion) of nature, a planet of infinite abundance, and a planet of infinite resilience. If there were such a fiendish beast as Satan (There isn’t. Satan is a mere metaphor for the evil that dwells like a wolf on a leash within every human soul), he could contrive no more effective way to wreak his havoc than to plant these cancerous lies into the minds of humans.

Not sure I’m tracking on the issue of Substack notifications.

I do a lot of self-talk, and just about every time I go for a walk I tell myself at some point during the trek: “This was an excellent decision, Kenneth!"

On the subject of dusting I am reminded of the poem ‘Dust if you must' by Rose Milligan:

“Dust if you must, but wouldn't it be better

To paint a picture, or write a letter,

Bake a cake, or plant a seed;

Ponder the difference between want and need?

Dust if you must, but there's not much time,

With rivers to swim, and mountains to climb;

Music to hear, and books to read;

Friends to cherish, and life to lead.

Dust if you must, but the world's out there

With the sun in your eyes, and the wind in your hair;

A flutter of snow, a shower of rain,

This day will not come around again.

Dust if you must, but bear in mind,

Old age will come and it’s not kind.

And when you go (and go you must)

You, yourself, will make more dust.”

I just got your walking book from my local library and can’t wait to get started. Love this essay and all the thoughtful questions you ask. I just finished reading a book called “open-air life” and one of the most interesting things to learn was about swedens property laws and how most land (even private owned) is open to the public!