The first night I slept a few feet from this tumbling river, the sky was clear. I’d left the rain fly off my tent and went to bed early enough to watch the darkness ease in. Every time I woke up, Cassiopeia had moved only slightly. I lay there and watched her in that clear, dark sky brightened only by the Milky Way. Moon was, I think, low in the east and hidden by the Rockies surrounding us on all sides. She was two days past new and I was looking forward to seeing Her out there, but there was only one truly clear night and I didn’t spot moonglow once.

I like Moon: She’s generous. She makes space for all Her star companions to shine in their turn.

There was a light amongst the Cassiopeia constellation that I’d never noticed before. Bright and broad, leaving grainy streaks behind it, like a comet. Maybe it was a comet. Maybe not; Cassiopeia has many more stars and star clusters than I could see from my sleeping bag under the light mesh of my tent.

I woke up many times that night, Cassiopeia always up there, the river’s rushing movement over rocks a soothing constant. At one point a large, superbright shooting star streaked past and I smiled myself back to sleep.

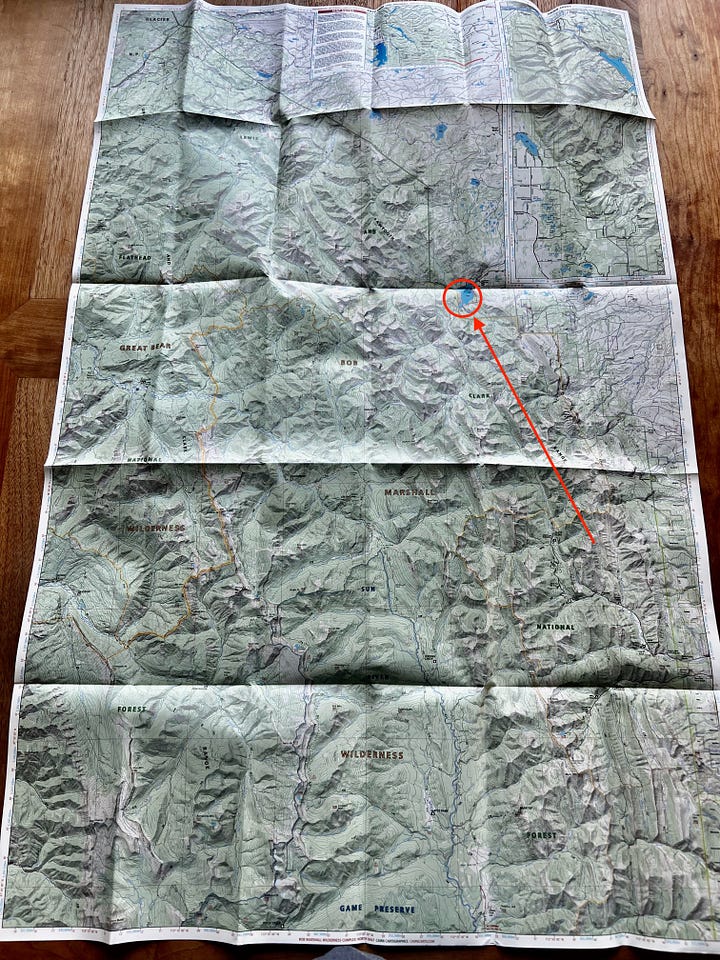

This was my second year on a volunteer wilderness trail crew with the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation. It’s beautiful out there, though I’m not sure I’m all that suited for the work itself. My left knee objects to almost everything these days, and the rest of my 47-year-old self likes to remind me how much we enjoy sitting around reading books, maybe picking chokecherries. The nine-mile trek into our campsite—on a day topping 100 degrees Fahrenheit (around 38C) and soaked in wildfire smoke just harsh enough to grate in my lungs—with 30-pound packs made me heartily wish someone else would set up my tent and help dig the latrine, much less get going with the saws, clippers, and Pulaskis the next day. (Someone else did dig the latrine—a woman who’d never been camping in her life and chose to start by spending six days laboring in a wilderness area with a bunch of strangers and who had the best attitude about discomfort I’ve ever met. She might be one of my new favorite people. My left knee and I could take some lessons.)

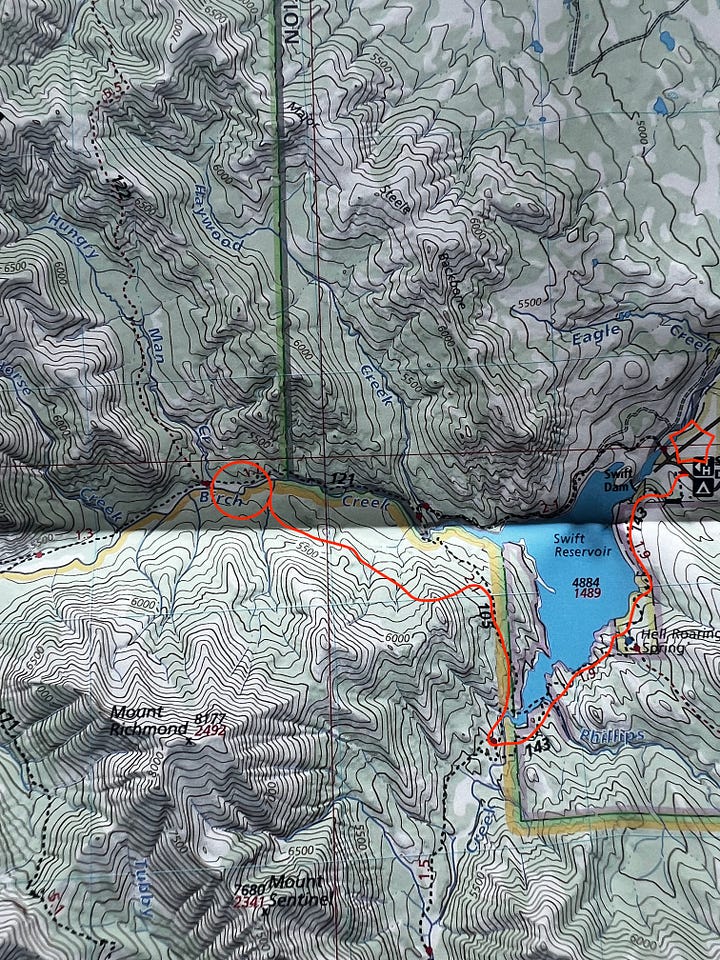

Complaining knee aside, there is nothing I love so much as being out there, in the mountains, a mid-sized river—they call it a creek, North Birch Creek, but unless someone can give me a good reason for calling an entity that large a creek, I’m going to think of it as a river—rushing constantly a yard or two away. This wouldn’t be everyone’s idea of an ideal place to spend a week, but it is mine. I’d like to sink right into it, become part of the calf-high lodgepoles and aspens regenerating a thriving forest after the 2015 Spotted Eagle Fire burned well over 50,000 acres.

It was something else to spend that kind of time in a forest doing what it evolved and was cultivated to do, growing green again after a thorough burn. To look at the grey-white snags standing tall in the high winds that first day and think about what all this greenery would look like again in twenty years, or ten.

Common nighthawks soared and dipped high overhead each evening as we ate dinner and cleaned up, and a bluebird crossed my path once, which always surprises and delights me because they’re so pretty and I don’t see them often, but there was no sign of larger animals—not much food for them, though there were plenty of tracks on the unburned areas a few miles from the trailhead.

There will be plenty of food eventually, though. That’s the magic of these cycles, and part of why the increasing intensity of wildfires is worrying—huckleberry rhizomes, among other crucial foods, can be damaged by too-hot fires—and why intact, connected ecosystems for wildlife is so important. It’s also one of the less-acknowledged damages wrought by absolute private property laws: the disruption of lifeways for animals, forests, rivers, and everyone else out out here.

Being on a volunteer trail crew is nothing like being on the non-volunteer crews with their ten-day stretches of eight-hour-plus days. The BMWF calls trips like mine “volunteer adventures,” which makes me cringe but I can’t disagree with. You’re in the wilderness, often deep in it, by choice; pack mule leaders, also usually volunteer, help with bringing in food and cooking supplies; and the BMWF crew leader does all the (surprisingly good) cooking. I still wouldn’t call it a vacation, even for people like me who thrive on being out there. We’re there to work. It starts at eight, which means having breakfast, packing lunch, doing dishes, and making camp bear-safe by then; and ends at four, by which time my aforesaid 47-year-old self usually has had more than enough of whacking out backslope with a Pulaski or moving rocks or taking down small trailside trees with a handsaw.

The three breaks we get make me feel lazy—I’m not sure that paid trail crews get breaks—but I live for those quarter- to half-hours. To sit on a charred log eating trail mix and hearing nothing but air in the foliage-less trees and a persistent woodpecker somewhere out of sight. To watch the light shift along those mountainsides. To spot snowberries and poke at the masses of Oregon grape, and to watch a river that slips through the valley like time itself.

Or it might be that time is slipping through us like the river. That’s what being out there does for me: it turns time into water.

Those who’ve read the introduction to my book-in-progress No Trespassing know a smidge of the attachment I have to this particular land, the edges of what’s known as the Badger-Two Medicine. It’s why I signed up for this particular trail crew, to serve that land in some way. We were meant to work on a different trail, accessed from the north instead of the east, and located more in the heart of the Badger-Two Med; fortunately, Forest Service managed to figure out another project when the first location was nixed due to nearby fire.

I can’t tell you why I love this land so much, but I do. I’ve been attached to it since following news of the oil lease cases from back in New York, years before I returned to Montana. As far as I remember, I’d never physically been in it until last year, though my mother tells me we spent some time there in my teen or pre-teen years. I don’t know. My only strong memory is of the paleontology summer camp I attended in that area when I was eleven, at Egg Mountain outside of Choteau, and we spent plenty of time driving around that part of the state over the years to visit my grandmother.

That landscape, especially the Rocky Mountain Front, has been showing up in my writing for nearly 30 years, since my second semester of college. I can’t explain that, either.

At the annual Gathering of the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance (an organization formed in 1982 to stop oil and gas leases in the Badger-Two Med) last year, Blackfeet artist and Piikani language instructor Jesse DesRosier talked about the connection that the mostly white settler audience expressed feeling with that land, a love for it. Imagine then, he said, how much deeper the relationship is when it goes back sixteen thousand years.

I’ve been thinking about what he said and how he said it ever since then, and I thought about it more when we hiked in that first day through smoke-filled, oppressively hot air past juniper bushes and bear tracks; and later in soaking, chilling rain among low-growing chokecherry and kinnickinnik, water suddenly everywhere.

It’s what I think about most when I’m writing about or researching land ownership in particular, and what probably makes me most sad about it: that relationship. What it means, how little of it I can possibly understand, and what it has meant—what it continues to mean—to have settlers like my own ancestors and attendant value systems of domination and separation paradigms walk in and say, “This is mine now.” And what it takes to keep justifying and glossing over that theft, the stories that have been crafted and taught and enforced to make sure it stays that way.

I don’t think our societies will ever be able to begin solving our many problems until we both sit down and walk with that reality for a really long time—a historical reality but also an ongoing one. It’s an unimaginable destruction, layered on top of the fundamental injustice of the kind of private land ownership that was itself imposed and fought against for centuries among the European societies that then forced themselves upon people and lands across the world.

There’s a constant tension, too, among the private lands abutting the public, of what uses and damage the laws allow in one versus the other and what that says about societal values.

Rarely is whose land we’re all on, and how that land became others’ “public” or “private,” truly part of that conversation. Some in conservation speak of a “continuing story of stewardship,” but the reality is a rupture that very few settlers are willing to face, including those of us who claim to care about conservation.

Then there’s the question looming over all of that, of what it means to have a culture so bent on domination that the only way it can keep itself from destroying life is to severely limit interaction by making some of it off-limits. What would it take to interact with our world, including the human-built world, in ways that make conservation efforts not obsolete exactly, but increasingly unnecessary? A world where you don’t have to run away to mountains or wildlife refuges to breathe clean air and listen to birds instead of traffic? Where the animals don’t need refuges to survive? Where your caution is around not attracting bears to your camp instead of avoiding the infinite ways humans harm one another?

I’ll probably keep doing these trips. It’s not about giving back to the not-for-profits doing the work of conservation. It’s about serving the land herself in whatever way I’m capable of doing, despite the objections coming from my aging knees. Maybe it’s about continuing to strengthen a connection to land I don’t even understand, a sense both of responsibility and joy as well as care—a feeling that, frankly, I don’t have many people in my daily life to talk about with.

I spend a lot of time walking the forests and mountains in my own part of Montana, west across the continental divide from the Badger-Two Medicine, and mostly I talk with the land herself, asking what she needs. She misses her people, is what I’m often thinking.

Maybe that’s something real, or maybe it’s just what I want to be able to think because I’m out there waiting for snowberries to blossom, and watching the particular way that ponderosa pines hold frost on their needles, and listening for the liquid raven call I only hear when alone in the woods, sitting among the trees wondering what on earth everything is all about. Always waiting for time and relationships to feel fluid again.

Most of our trail crew went in the river after work every day, including me, and it was still frigid, almost as cold as snowmelt, ankles achingly numb within seconds. We each found our own shiver-holes to dip in, gasping for breath as the cold, rushing water snatched at our lungs. Or at least I gasped for breath, trying to stand it long enough to get water in my hair and rub off the worst of the charcoal on my arms and face. My favorite spot was closer to camp than the others’; I saw a small patch of white sage growing on the gravely bank, hidden by bushes, and wanted to be near it.

The last full work day, it started raining around four in the morning and didn’t fully stop for over twenty-four hours, after we’d packed up and left camp. It rained so much the trail became a succession of elongated ponds, with one section a full-blown stream fed by a mass of trickles sliding down a mountain through snowberry and young aspen. Two days left in the sun at home and my hiking boots were still wet and mud-caked from that day; I’d spent the hike back to camp wringing water out of my leather work gloves. That day, walking through rain-drenched meadows where purple fireweed grew taller than my head, our crew leader said what I’d been thinking, that it looked like something from Lord of the Rings. The edges of Lothlorian, I thought, after the Fellowship landed above the Falls of Rauros and just as Boromir was battling with his own desire for the Ring.

Even looking at this photo from that day, downstream from a triple-tiered waterfall, I can feel it. The deep chill of being soaked through, every layer I’d put on wet or damp, the rush of the river, the way it clouded into milkiness later in the day as the weather stirred up silt and mud far upstream. The rain coming in waves of gentle to pouring, soaked up by soil that my Pulaski showed was fire-dry less than an inch down. And the green of it all. It reminded me of the ending chapters of The Overstory: Ask yourself, what does green want us to do?

I could have stood in the rain and watched those trickles for ages, slipping among moss and shale to eventually join the stream and then the river below, each state of water its own mark in a time-cycle, the movement and seasonality more real than anything I would see when I got back to places with WiFi and cell phone service and a bed without rocks under my back.

(This is not entirely true. Before transferring the first messy draft of this from my notebook to the computer, I was in the garden absentmindedly munching on late peas, checking on the sweetgrass—which is doing well—being happily surprised that the tobacco seedlings I’ve been trying to coax into growth finally seem to be getting somewhere, tying up some massive raspberry canes, and digging up a pile of fingerling potatoes for dinner while two spotted fawns munched grass on the other side of the fence and some ridiculous baby turkeys chortled around the house. That’s all pretty real.)

North Birch Creek from my spot among the white sage.

The next morning, as we packed up camp, the sun covered the clouds with orange-pink light and a rainbow kept us company all morning. A dense fog suddenly came in and just as suddenly left. I’m not sure any of us cared much about our sodden shoes and wet tents, but if we had, the land and sky that morning, and the rainbow that wouldn’t quit, would have burned it right out of us.

I’ve used river and water metaphors for everything human more times than I can count. I’m pretty sure I used it in my last book, writing about topographical maps, and I know I’m using it in the current one—not just to talk about water itself, but to talk about people and how we approach life, problems, relationships, and time. There are so many good metaphors for these subjects, even though I’ve been wary of metaphors for a while now because too many of them feel empty, but I never land on a better one than water.

Water free-flowing and fluid, drenching fire-baked land, widening and constricting, never really ending but caught in an endless cycle full of grace. Like time embodied, dancing.

what does green want from us. Thank you for sharing your experience in such vivid beautiful detail—i feel like i just got to spend time along the creek-river and in those regenerating spaces too. And this: “What would it take to interact with our world, including the human-built world, in ways that make conservation efforts not obsolete exactly, but increasingly unnecessary? A world where you don’t have to run away to mountains or wildlife refuges to breathe clean air and listen to birds instead of traffic? Where the animals don’t need refuges to survive? Where your caution is around not attracting bears to your camp instead of avoiding the infinite ways humans harm one another?” yes. To imagine is at least a way to move forward on some level—but i constantly think about land management and conservation and what it would be like to know something intrinsic and old about the lands we live on so that we wouldn’t have to cede the care of them to population studies and regulations. It feels like an enormous failure really. But that doesn’t take away from what a beautiful reverie all of this was to read. 💜

Loved this, and love the calm, contemplative vibe of it.

I wonder about the people who say "this is mine now," about how much time they actually spend in the lands they claim to own - as in, out in the wildness of it, instead of within the human-build structures they've placed within it, or even worse, in a skyscraper hundreds or thousands of miles away. Doesn't immersion teach a lesson about owning? Like those bear tracks, saying, "you think you can ever truly control all this? Look at these paws."

Sometimes I feel like abstraction is the great enemy of the natural world, where we cook up these Sweepingly Grand Ideas and generalise away all the details. A true dumbing-down of the world in the service of unchecked capitalism, where the idea goes to the point of production and someone makes the decision to slam the door on all those inconveniently messy details because they're "impractical".

I worry about this, because I love those Big Ideas! (And write about them.) Who doesn't get excited at such things? But - you also have to leave the door wide open, and let everyone stroll through and present their complications and treat them respectfully (if they're presented respectfully) because that will make your ideas smarter and wiser and more useful. I get how that's hard, but...

But I really feel like a lot of problems can be solved by letting some business-powerful people be truly *in* some parts of the world before they make sweeping ownership decisions about them. Let the land speak to them in all its voices, adding to the argument in ways that often bypass simple language. Close the distance completely and open all the doors wide. I bet it'd help.