I’ve been fully immersed in a Master Naturalist course (through Swan Valley Connections—thanks to the inimitable Chris La Tray for talking about how awesome they are; I’m sure he’s written about them at some point), and was planning a post about grizzly tracks, the grapefruit scent of grand firs, caddisflies (among my favorite creatures), and the colonization of science, but on the morning of the third day of the course, I got a message from my father that his cousin Zhenya had died.

It’s been months since I wrote anything here about Russia. I’ve been pretty immersed in Montana both physically and mentally; I also have trouble knowing what to say. Because I have close family there, there are too many things I have to write around. Here in Montana, I can say whatever I want about Putin. They can’t. Many of the things I think and say are illegal there. This is a reality that those of us who’ve only ever known freedom can have trouble grasping, a reality that for various reasons was always part of my upbringing. You learn to live dually, split your mind, develop careful boundaries of trust, and often learn that trust just isn’t possible.

Although much of the English-speaking world has stopped talking about the invasion of Ukraine, anyone who pays the slightest attention to Russia’s current reality and the centuries of history in Eastern Europe* is worried. I’m worried.

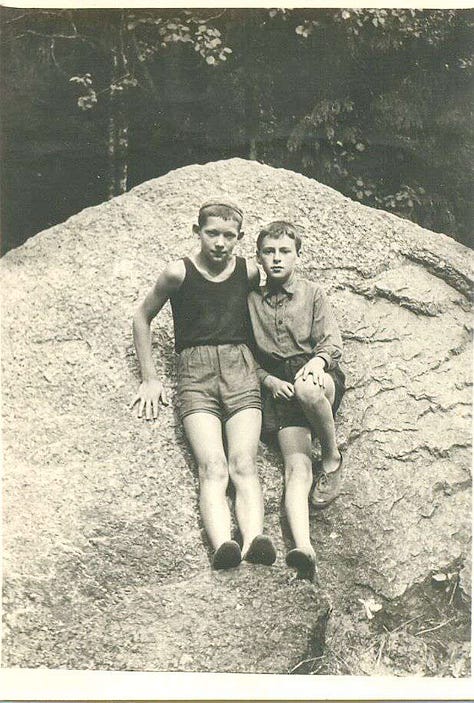

But we all, also, live in the ebbs and flows of personal and public concerns, and today I’m setting aside geopolitical worry to honor a personal loss. Zhenya and my father grew up more brothers than cousins. In Russian, the words for “cousin,” dvoyurodnyy brat’ or dvoyurodnyy syestra, contain the words for brother and sister. Partly because of how close my family there is, and partly because of the culture, his daughter Irina and I have always considered each other sisters rather than distant cousins.

Zhenya—Yevgeny Yassin—was a public figure in Russia, an economist with respect and influence. When the Soviet Union collapsed, he was involved in forming a new government and eventually became Minister of Economics. For many years he was the academic supervisor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow (not pictured above; that’s Moscow State University). He had strong opinions about the promises of the free market and the failures of communism, opinions that took the rise and power of Russian oligarchs to shake. And he was a stalwart advocate of human rights, something his daughter, my sister-cousin, continued: she ran a humanitarian organization in Russia until Putin outlawed it several years ago.

Zhenya was also someone who made me feel more loved and welcomed than almost anyone else in the world. Even though I didn’t meet him or any of the rest of my Russian family until I was fourteen, he made me feel like we’d known each other forever, an integral part of a close-knit family despite the fact that I could barely communicate in the language. He often called me maya malen’kaya mat’, “my little mother,” because he said I looked like his mother. One of my middle names, Evgenia, was given to me in his honor. It’s one of my lasting personal sadnesses that I haven’t been to Russia in over a decade, and lost the chance to see him once more.

When my grandfather in Leningrad died in the late 1980s, my father was still living in exile, unable to return to the Soviet Union after leaving in 1974. I doubt I’ll ever forget that day, the call from my aunt on our party line phone in Polson, starting to understand for maybe the first time what it means to be separated from your family, forever as far as you know. The kinds of fractures it creates. The kinds of bonds it tries to cut. I don’t know if there’s a greater evil humans inflict on one another than forcing families apart. It is something that Russia, like all other places with imperial ambitions, has excelled at throughout its history, particularly when it came to Jewish people, which my family were. My parents’ story has a little more choice in it, but in the end the Soviet authorities still told my father he could leave with my American mother and my older sister, or stay, but if he left it would be forever.

That Zhenya always managed to make me feel like we’d never been separated, never seen our family fractured, is a quality that today stuns me with its loss. To make people feel that welcome in the world as part of your nature is something I wish I could live up to.

My stepmother’s great-aunt, the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, lived for many years in exile and lost her daughters to starvation and the gulag. Like millions, her life in Russia was defined by suffering. And yet what she created in return was poetry, of love and life and a piercing view of the world:

“I am happy living simply:

like a clock, or a calendar.

Worldly pilgrim, thin,

wise—as any creature. To knowthe spirit is my beloved. To come to things—swift

as a ray of light, or a look.

To live as I write: spare—the way

God asks me—and friends do not.”

Zhenya didn’t have a simple life, but he, too, cultivated a sharp mind while spreading love and liveliness all around him amidst the realities of the Soviet Union. He is one of the many people who taught me, unintentionally, that what is worthwhile in life is always simple. Maybe a few shots of vodka and debates over politics and economics and literature long into the night. But most of all, that where our true human potential lies is in laughter, hugs, a meal, stories, some good friends, a much-loved family, and mourning the loss of the same. In our connections to one another.

I heard once that who a person is, their fundamental human self, is defined in part by who claims them. Who their people are. Zhenya gifted me that, a profound sense of belonging to people. He will be mourned by many, his public service and accomplishments lauded in newspapers across Europe. But me, I’ll light a candle tonight, and feel the loss of his ready smile, his keen conversation, and how easily he made me feel like I belonged.

The morning that my father’s message about Zhenya came, I drove again the too-long route to the Master Naturalist course, watching sunlight strengthen above a mountain range, rising through cloud cover just thick enough to hide its full brightness but thin enough to spread gold across the sky. A flock of Canada geese winged overhead in the direction of the sun, and as I watched, a few of them somersaulted in the air, wings folded, their flips in that golden light the kind of pure earthly joy that arrives, also, in the smile of someone you love.

*Two good books on that region I read recently were Neal Acherson’s Black Sea and Orlando Figes’s The Story of Russia. I also still recommend Konstantin Kustanovich’s Russian and American Cultures: Two Worlds a World Apart for a closer understanding of Russian worldviews.

I'm sorry but only for the loss of Zhenya, but the loss of the time you didn't get to spend with him over the years.

I'm sorry for your loss, Nia. Thank you for introducing him to us. Thank you also for reminding as that suffering is universal. May our compassion rise to meet it.