There are a lot of new subscribers here at On the Commons, thanks, I think, to Mike Sowden’s overly generous interview with me on Everything Is Amazing. (I’m looking forward to the second half where we geek out over science fiction because I am always ready to geek out over science fiction, which is far more interesting than any words I put out in the world. Let’s talk about Murderbot or A Memory Called Empire and who gets to define personhood, or how climate collapse and societal decay intertwine in The Parable of the Sower, or the power of enforced and self-policed speech, and even perception, in The City & the City, or resource governance and self-determination in The Expanse . . . )

However you got here, welcome. Feel free to ask anything (within reason), either in the comments here or by emailing me directly. As always, if it’s not your thing, no hard feelings. And if you want to go for the paid version but can’t pay, just email me the code word “tribble” and I’ll set you up, no questions asked.

There are three basic formats to posts from On the Commons (four with the Threadable reading circle, which you can read about here; just scroll past the part about the bear that got into a neighbor’s outdoor chest freezer):

1) intermittent longer essays on a variety of subjects, from highways to authoritarianism;

2) upcoming chapters from my book-in-progress No Trespassing on private property and the commons (these will come slowly over at least two years); and

3) what I call “walking compositions,” weekly-ish, which are a kind of triptych three-section mini-essay combined with a curated list of reading, podcast, and sometimes video suggestions.

I haven’t explained the walking composition concept in a long time (have I ever?), but there’s a story behind that title.

A few years back, when I first started writing my book A Walking Life, I was lucky enough to be accepted at an interdisciplinary artist’s residency at the Banff Centre for Arts & Creativity in Banff, Alberta, Canada. The Banff Centre is a gift to any artist—space, time, beauty, long walks into the mountains or along the river, and really good food. I’ve attended residencies there twice and always dream of going back. Except for the part where the institution is largely funded by tar sands oil money. Which makes it . . . difficult.

I applied for this one because Pico Iyer was heading the writing portion, and the entire residency was structured around the ideas he’d expressed recently in his TED talk and accompanying book The Art of Stillness. It was an Art of Stillness-focused residency that brought together musicians, writers, dancers, choreographers, composers, and visual artists. (Richard Reed Parry of Arcade Fire led the music section of the residency, and, in addition to being an authentically interesting and down to earth person, managed to completely change my mind about cover songs, which I had never liked—“You mean folk music?” he said.)

The second residency I attended there was one of the writers-only ones and, much as I enjoyed it, I’d take an interdisciplinary group any day. I learned so much from the other artists in that first residency, from the dancer who would spontaneously perform for me outside my studio window, to Christopher House, the choreographer who guided a movement meditation for an hour every morning and who reminded us throughout each session that we were “exploring the deep ethics of optimism,” which I’m still attempting to achieve.

One of the composers in my group, Alex Mah, created works like nothing I’d ever experienced before. In one performance, he had a pile of words on pieces of paper, and sang a kind of dialogue with another singer as they pulled words out one by one. It sounds simple but the way he did it was not. I wish I could fully describe what he does because not much of his work is online. There are some videos, like this one, but they don’t really capture the sensory experience of watching his work, much of which incorporates pauses in a way that gives them texture, a world of their own.

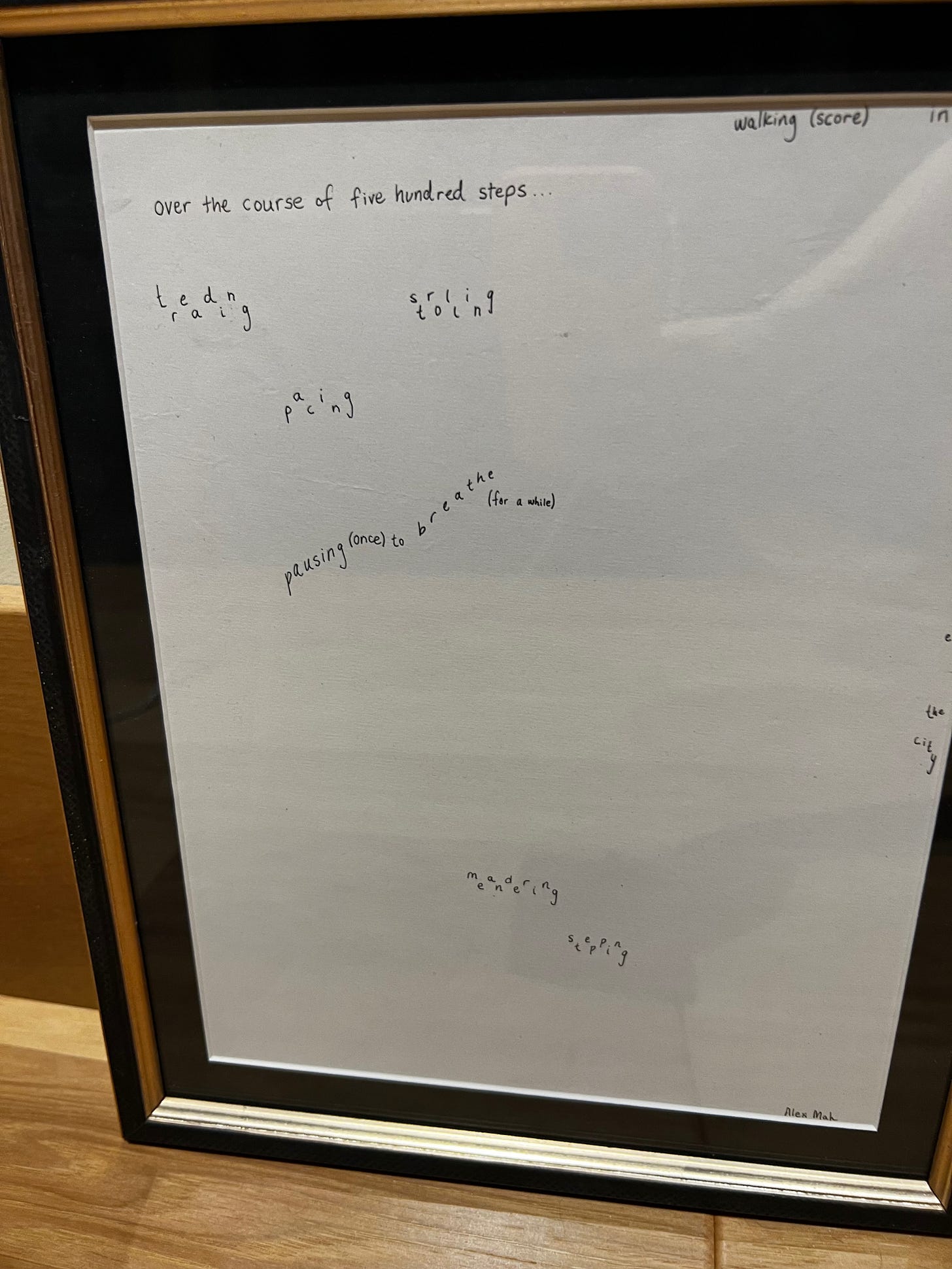

As we were preparing to leave the residency at the end of two weeks, Alex handed me a sheet of paper with what he said was a walking composition for me, like a musical score.

I’d learned by then that when Alex structured words and spaces in particular ways it was for good reason—he wasn’t just decorating the paper. The composition isn’t only the instructions written down, the strolling and treading and so on; it’s the way it’s shaped on the page, how he wrote it. Which, six years later, I still struggle to understand. The only way I’ll ever be able to gain some insight is by continuing to do the practice.

I started performing the walking compositions literally: 500 steps each day, strolling, meandering, pausing once to breathe for a while, all of it. I used Instagram as a small way to share that experiment with the world and ended up pairing a quote from something I was reading or listening to with a photo I took while performing the walking composition.

When I left Instagram and started this newsletter, I pulled that practice over with me. It’s changed, mostly because my words aren’t limited to a brief social media post. But the picture, quote, and thoughts all still entangle themselves in what I experience as a walking composition.

The topics of these triptych mini-essays range freely, from gardening experiments—why won’t the beets grow? (it was the soil; thank you for the advice, elm) how do we have zero cucumbers one year and a zillion the next? and always, always, the battle with knapweed and thistles—to skiing to hunting season to Russia to books I’m reading, whether science fiction or research on private property and the commons. Pretty much anything I end up walking with.

Which often might feel tangential, aside from the gardening with its obvious seeds and soil and commodified food aspect. What does this have to do with the commons?

Part of the reason I think the commons is so important to reinvigorate is because enclosure isn’t just of land and resources but of ideas and experience. A sense of scarcity and competition infiltrates every aspect of our lives. Even the idea of opening up a country’s history to narratives and realities that had previously been oppressed, if not outright killed, is seen as a threat to survival. Of what? Of identities, of a story we’re told, and tell ourselves, about what a society is and what it can be. And so that story becomes enclosed—impervious, its defenders hope, to outside influences.

These stories are commons, too.

Every thought we explore, every cucumber seed we plant, every forest we breathe in and path we walk, every essay that goes viral, every individual experience denied for the sake of another hot take, every child struggling over a poorly-worded math problem or a grief they’re not allowed to articulate, every fence posted with a “No Trespassing” sign, every community destroyed in extraction of a commodity it lives near, every life we injure or enrich, is the commons. Simply by existing, we are in the commons and of the commons.

I touched on this idea briefly toward the end of the original essay I wrote on the commons for Aeon,

“Troubling implications of our fetish for private property abound, well beyond the question of land ownership: the rights of companies to patent and therefore privatise seeds, taking access to food out of the public realm. Battles over open-source computer programming and whether libraries should be privatised bring into question who gets access to the powers of information and creation. . . . our very genes and tissues can be collected, traded, tested, and sold as private property, a prospect many people find appalling. It’s a long road from owning a mobile phone or a quarter-acre lot of surveyed subdivision to owning your genetic information, but all of these examples fall into the question of who owns what. Arguments in favour of preserving the public commons against private interest could be made for every one of them.”

and will explore them more fully in No Trespassing (an overview of that project is here).

When I told Alex Mah after a couple of years that I was still using the composition he wrote for me, he gave me another that instructed me to walk backward for a hundred steps. Which I did, on an ocean-pounded beach in Norfolk, on my way to view a village where 800,000-year-old fossilized hominin footprints had been found before they dissolved into the sea. What did I learn from walking backwards? I don’t know. But it’s something that I remember, the press of my boots on the sand, the roar of the relentless ocean, the feel of the mud cliff walls crumbling as I pulled out a tiny piece of flint rock.

I’ve walked enough by now to know that it’s those memories full of sensory detail—traffic on a city bridge in Pittsburgh, chickadees calling outside my home in early spring, the broken cobblestones of a Boston sidewalk, the particular scent of imminent snow, a child’s scream of frustration, a lover’s glance in the sunlight—those are the memories that stick around, that make a life.

I retained the title “walking composition” because I’m still walking, still thinking, still reading, still wondering, still taking a photo and pairing it with a quote. So is everyone, even without the photos and quotes. I’d love to have us all head out right now, every day in fact, and each find our own walking composition. Isn’t that, in a way, what resistance is—finding and fighting for our own ways to be in the world? Isn’t that what living is?

Walking is always a composition. We compose our lives by walking through them, however that looks and whatever that entails. Every part of that experience is our commons.

I’ve put over 5,000 miles on these boots. We’ve meandered and wandered, trudged and trespassed. We’ve walked so many stories together, and I hope will walk many more.

That’s so cool about walking composition. And that zucchini!

"Enclosure isn’t just of land and resources but of ideas and experience."

"Isn’t that, in a way, what resistance is—finding and fighting for our own ways to be in the world? Isn’t that what living is?"

"Walking is always a composition. We compose our lives by walking through them, however that looks and whatever that entails. Every part of that experience is our commons."

Hmm. Wow. Lots to chew on there. It's almost like a little Meaning of Life 101 gift package. But more like Meaning of Life 301; not immediately obvious until you stop (walk?) to think about it and then it's like, of course. This idea of extending the "commons" concept beyond resources to the lived realm of experience, ideas, testimony and difference - openness, respect, curiosity, attending - is intriguing. It's true, we live in a world in which everything that ever happened and was experienced.....legitimately exists. Yet this experiential realm isn't shared equally, or even seen. I'm just starting to think through a possible project or paper about trust and related themes, so this feels connected. Which I suppose, is the point of the commons: that everything is connected.

That's a fascinating story about the Walking Compositions, thanks for sharing that.