Reading "Commentaries on the Laws of England in Four Books," by William Blackstone

Threadable-adjacent reading discussion on land ownership

The most recent Threadable reading* for Land Ownership was a selection from William Blackstone’s 1753 book Commentaries on the Laws of England in Four Books, Book II: Of the Rights of Things, Chapter I: Of Property, in General.

*(https://threadablenative.page.link/Rxp8yegeZ1vXy4u19 if you want to try the Threadable app and need the link! Only works on iOS/Apple devices for now.

For anyone new to On the Commons an overview of this project is here. Please feel free to comment or email me with any questions.)

Blackstone’s Commentaries is in the public domain, and there are many different places online where you can read the text. Several of the sources retain the original text style, though, so you get those “s” letters that are shaped like “f” and it can make the reading a little difficult. The Google Books version is a 1979 publication, which is kind of fun to read. But given the factors of style and font, I found this one most accessible to my modern and tired eyes.

Note: There is one untranslated Latin line in the link above: erant omnia communia et indivisa omnibus, veluti unum cunctis patrimonium esset. Ballentine’s Law Dictionary gives the translation as, “All things were common and undivided, as if there were a single patrimony for all.”

There’s been a fair amount of dense reading in this project, and I want to make clear again that my interest in these texts is not academic. I really want to get to the roots and damaging effects (both historical and ongoing) of the current-day private property regime. Not just what it is but how a culture thinks about it, how people are trained and taught to think about it. What most of us assume is true about land ownership.

I doubt much about private property law will change in my lifetime, if ever, but I also think there’s more hope for change if we know the justifications and rationales that underlie beliefs about private property—beliefs that are intertwined with how the dominant culture views a relationship with nature, with the rest of life.

I’m not sure if it’s possible to overstate the influence of Blackstone and his Commentaries on legal thinking in general, as well as private property specifically. At the time he was writing, English common law was, from my understanding, a mess that even experts, much less lay people, had little hope of understanding. Blackstone took the mess and organized it, with lengthy explanation and legal philosophy. He is particularly known for his examinations of liberty, justice, and the role of government, and his Commentaries were very influential in the nascent United States, including with regards to property law.

Blackstone’s legal theories, and those of John Locke (which will be the next reading), seem to be baked into the foundation of how the dominant culture we live in thinks about private property in general and land ownership in particular. (Even though their theories disagreed, their utility for private property has been complementary.) It’s important, maybe even essential, to unearth the ideas and writings that exist in the law’s DNA.

Maybe more important than the law is the psychological DNA: the conscious and unconscious ways that most people—even many who question the dominant culture or don’t like it—think about land, ownership, and private property. The reason that so many can proclaim “private property is bedrock” without question.

Which makes it all the more interesting that Blackstone himself admits straight out that there is no actual basis for private land ownership.

“There is no foundation in nature or in natural law, why a set of words upon parchment should convey the dominion of land.” So why, then, do we have it? And why do we continue to defend it? It’s obvious that human societies of any size need a way of managing and sharing land, water, wildlife, etc.—but it’s not obvious why private, individual ownership needs to be the answer.

Blackstone engages in a long discussion of the right of occupancy—how occupying land originally gave a kind of temporary ownership over it in the form of exclusive use during a person’s lifetime, but it wasn’t something that could be passed on as an inheritance. Nor did occupancy necessarily grant adjacent rights that in places like the U.S. today are considered part of the “bundle of sticks” of land ownership, like the right to exclude others from the land. Trespassing laws are relatively recent inventions.

In one of a series of frustrating logical leaps, Blackstone then argues that occupancy did in fact give one permanent ownership of land, if you take into account the advent of agriculture and how a landowner/user had no incentive to cultivate their land, treat it well, and make it productive if their ownership of it were not absolute. The blithe phrase here, “it is agreed upon all hands that occupancy gave also the original right to the permanent property in the substance of the earth itself,” neglects not only his own failure to make any such case, but ignores England’s battles over enclosures of the commons, which had been ongoing for centuries by the time of his writing. There would have been no Kett’s Rebellion or other uprisings if “all hands” agreed that occupying the land by extension granted title to it.

The simple need of every human to eat, I suppose, didn’t qualify as an incentive to cultivate or care for land—an echo of the points in the last reading on Henry George about how “skin in the game” in the form of ownership somehow counts as “having a stake,” but skin itself, in the form of survival, doesn’t.

There are also a number of instances where Blackstone insists that chaos would ensue and civilization crumble without the security provided by private land ownership. A security that, as one reader pointed out, is a mirage.

Even if we pass over (and we shouldn’t) the incredible violence needed to make most of today’s private land ownership possible, it has not granted protection from tumults; it has not guaranteed “the good order of the world.” Blackstone, however, doubles down on this many times, arguing that private property is necessary for civilization to thrive.

His arguments neglect, again, England’s long and ancient history of commons systems of land use, not to mention Ireland’s Brehon laws that governed common land use, which would have been fairly recent history—Brehon laws were only fully dismantled in the face of English colonization crackdowns in the 1600s. It’s hard to imagine such an eminent jurist, someone who taught at Oxford and was for a time a Member of Parliament, would have been ignorant of these realities. He even, within the text, specifically pointed out the necessity of the commons themselves remaining in the commons—forests, “waste” grounds, wildlife, etc.—for civil society to exist.

This seems to be a central theme for Blackstone. Reading and rereading a long section explaining how inheritance of property came about, I was confused about a passage that seemed to reiterate that land ownership is made up, and therefore inheritance law is also made up, which led to a brief explanation in Threadable from a reader of private property’s codependency with the state.

The argument that property ownership is a “civilizational necessity,” goes back to a central problem I see with these legal philosophies, at least as related to property law: they often seem to be written and argued—not always well—in order to lay down justifications for a regime that already benefited only a few. Blackstone has been one of the most respected legal scholars in Western history, and his writing here still reads as grasping for straws. Are all these arguments in defense of private property simply about bolstering the integrity of the state and the privileges of its nobility and other elite landowning citizens?

Not to put too fine a point on it, part of the whole issue of colonization is that plenty of societies manage land and resources just fine before someone else comes in and imposes private land ownership and commodification on them. Who’s really causing all the tumult and disorder here?

In the end, Blackstone’s case for private property reads as pretty flimsy. He has only one answer to the genesis of human ownership of land, which is, of course, in Genesis, Chapter 1 Verse 26, of the Christian Bible, which reads (King James Version):

“And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

Blackstone follows quotation of this passage with:

“This is the only true and solid foundation of man’s dominion over external things, whatever airy metaphysical notions may have been started by fanciful writers upon this subject. The earth, therefore, and all things herein, are the general property of all mankind, exclusive of other beings, from the immediate gift of the creator.”

This is hardly a basis for what a dominant culture might deem “civilized society.” Or maybe it is. Maybe it’s all there can be. Some amorphous fog of instruction from a few thousand years ago, a line that continues to play a defining role into how this culture treats environmental concerns—life concerns—like, say, clean water. Whether it was intended to be instruction to care for life on Earth or not, or to steward it, that isn’t for the most part how it’s been employed, at least not in modern times.

Except for perhaps the most devoted Christian dominionists, Blackstone’s explanation is simply not a persuasive justification for the kind of theft and dominion-based land grabbing that has defined colonizing societies for a thousand years if not longer. And far from a private property regime leading to civil society avoiding tumult, it in fact has led to land theft and hoarding, deep inequality and violent rebellions, and probably extensive environmental devastation even long before his own time. All of which continues in exacerbated forms to this day.

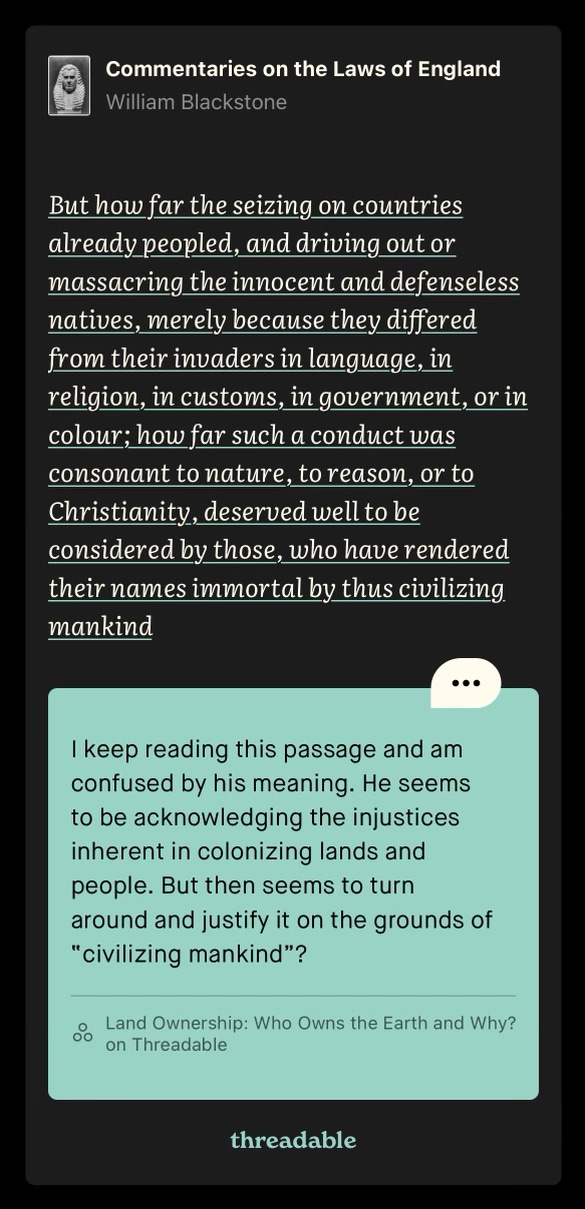

Blackstone contradicts himself on the subject of colonialism more than once, claiming that land ownership can only be of “unoccupied land”—that is, you can’t claim as your own land that other people are living on—but then finds a way to justify it (or at the very least fails to fully condemn it) on the basis of the “civilizing” impulse. Is he being sarcastic or serious? I can’t tell, but he doesn’t seem to have the courage to call out colonialism for the theft that it is.

He then, maddeningly, contradicts himself yet again—twice!—in the footnotes, first in trying to answer again where ownership originates:

“But how or when, does property commence? I conceive no better answer can be given than by occupancy, or when any thing is separated for private use from the common stores of nature.”

(Or, as I’ve come to put it and you’re probably tired of hearing from me, the first law of ownership: “I took it. Now it’s mine.”)

Followed in the next footnote with an acknowledgment that the land of North America did in fact belong to the people who were already living here, and also that similar types of shared property models used to be the norm throughout the European continent:

“Among the aboriginal inhabitants of North America there was no private property in land; but the territory or hunting-grounds belonged to the tribe, who alone had the power to dispose of them. . . . Something like this is discoverable in the earliest accounts we have of the laws of the savage inhabitants of ancient Europe. Property in land was first in the nation or tribe, and the right of the individual occupant was merely usufructuary and temporary.”

So Blackstone acknowledges that land all over the world he knew of was managed in various forms of collective ownership and use. And that the only right of ownership he sees is the right of occupancy. On what basis, then, is private, individual ownership of said land justified? He says it was “agreed on all hands” that agriculture and civil society made it a necessity, but makes no real effort to back it up, or to address the disagreement between this reasoning and his other statements regarding occupancy.

I call the contradiction “maddening” because, again, this thinking is baked into both the philosophy and the reality of our private property laws. It’s tangled up with the Doctrine of Discovery, which is still legal precedent in the U.S. and many other countries of the world, and with a narrow slice of Judeo-Christian ideas about humans’ relationship with the rest of nature and one another. (For further deep-diving into the entanglement of land beliefs, Christianity, colonialism, and white supremacist thinking, I recommend Kelly Brown Douglas’s 2015 book Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God, which I wrote about last year.)

In other words, despite this document being kind of a mess and riddled with honest to goodness logical fallacies, its intent—to defend private property as something societies need so that they don’t crumble into chaos—has been successful.

The other side of that success is due in part, I think, to John Locke’s notion that ownership in land is validated by one’s labor on said land. Which Blackstone disagrees with, arguing, with surprising clarity that,

“for mixing labour with a thing can signify only to make an alteration in its shape or form; and if I had a right to the substance before any labour was bestowed upon it, that right still adheres to all that remains of the substance.”

But we’ll save that until we get to Locke himself. After that it’s just two more readings, Nick Hayes’s The Book of Trespass, which is a fun read; and law professor Mary Christina Wood’s Nature’s Trust, part of which lays out the legal basis for dismantling private property rights over nature.

At some point someone is going to ask me exactly what I expect societies to do to overturn or reform private property law if I think it’s so awful, and the answer is that I don’t know, but a combination of Land Back movements, Rights of Nature, recognizing the commons and our dependence on them, and Wood’s ideas regarding the public trust and limiting private property rights over nature (especially for corporations) seem like a good start.

If you made it this far, you definitely deserve this sunrise from my daughter’s and my walk to school the other day.

I can't stop thinking about coverture laws and Blackstone's definitions of marriage, how a husband and wife become one person in the law and the person is the husband. The wife is basically erased. And that Alito referenced Blackstone repeatedly in overturning Roe. The roots of property and ownership lead back to disenfranchisement of non-white men, women, and children, as well as the land. Property as the root of oppression. This details in all of this reading are really fascinating to learn.

Once again I find myself dragged back to classics I ignored. Thanks.

Being charitable, it is not easy to wade through all the issues and all the situations for which one must account in a discussion of propery, without contradicting oneself. But it is absolutely amazing that one of the cornerstones of our law hangs together so poorly. Or maybe not. The Founding Fathers relied on both Blackstone and Locke, who were not in agreement on what one would think is a fundamental point, but they all managed to stumble to the same conclusion. "Without private property there is chaos."

Except that wasn't true and they must have known it wasn't. The enclosures (it would be interesting to know how much Blackstone knew about them or if he wrote anything about them) created chaos in their time, although I guess much of that was localized and spread out over many years, maybe not big news to England's educated elite. The colonists must have known about the enclosures, but they weren't relevant over here.

So, I guess we boil it down to the privileged getting to write the definitions that suit them, even when .they know better