I am currently at the Dear Butte writing residency, in Butte, Montana. In a vast state with varying skies I am stupidly in love with in every region, I’d put Butte up as a contender for having the prettiest and most dynamic of them. And the proudest crows. I thought the crows around my house were pretty happy in the fir and spruce trees, but nothing like the crows hanging out on the mining headframes around Butte.

Dear Butte provides a gift of time and space that I’m having trouble wrapping my head around. No workshops, no flurry of writing residency social obligations. You get to be by yourself! On top of that, it gives you up to ten days in the most welcoming, creativity-friendly house I think I’ve ever been in. I’m not exaggerating, I’d like to move in. There are photos of it in the Dear Butte link above.

On Monday, June 12th, as part of the community engagement aspect of this residency, I’ll be meeting with people locally for a walk and conversation about walking’s role in building community, and how communities tell their own stories. Details are here if you’re in the area and want to join!

I have an old box of embroidery thread that belonged to my great-grandmother. I don’t know if she used it much. I’ve never seen anything she might have made, and my own maternal grandmother had other interests, like flying planes and taking care of her small dogs and whole lifetime of service. Maybe there’s a reason I ended up with this box of thread skeins, some of which looked like they’d never been untied. Maybe nobody ever used them.

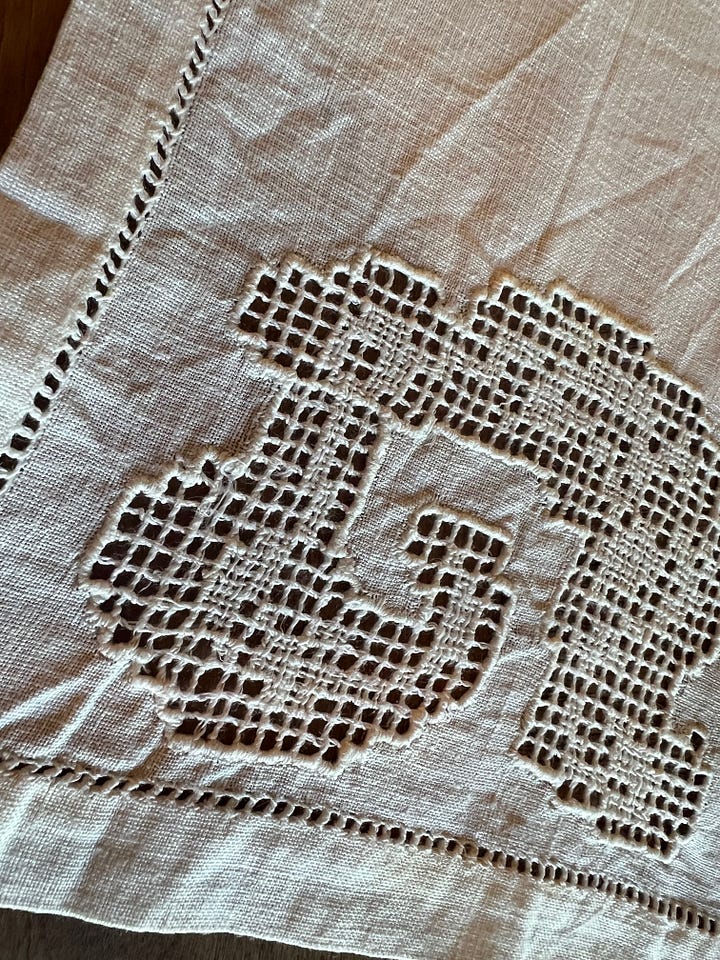

My other grandmother, the one who’d spent most of her life in Leningrad after leaving the Pale of Settlement that Jewish people had been confined to until the 1917 Russian Revolution, was another story. She embroidered colorful, elaborate pillowcases of flowers and birds. She cross-stitched table runners and made tablecloths out of a kind of picked-thread style that people in that part of the world still make: picking out and pulling threads in linen cloth to create patterns similar to lace. She was a metallurgical engineer and had, as I’ve written before, a life that was rarely anything but hard, but my father has told me that even when she got deeply depressed, she would sit down in the evenings and work on a tablecloth or pillowcase. She was always making something.

I shouldn’t say “even when she got deeply depressed.” There are rich histories to decorative arts all over the world, histories that I mostly don’t want to get into because they’re not mine to talk about. There are repeated themes, though, of stories told, of information shared, of enlivened connections to a living world. It makes me read differently the Danish folktale of the sister who knitted stinging nettles into shirts to turn her swan-brothers back into humans. What was my grandmother creating in those evenings? What pulled itself out of her mind and a lifetime of hardship and put itself into the fabric that now sits in my house? What is in the needle and thread that I’ve taken for granted most of my life?

While in Butte, I’m working on a couple of essays—one revision for an anthology that will be out next year, and another an overdue deep-dive about copy editing that I’m having fun with—and No Trespassing. With regards to that last, I finally picked up Hungarian socialist Karl Polanyi’s classic book The Great Transformation, which several scholars have suggested as a keystone book for the work I’m doing. I started it, and put it down again a few pages into the forward (by Joseph Stiglitz), after reading the summation that “market liberalism makes demands of ordinary people that are simply not sustainable,” and that in attempting to force an absolute free market and its consequences on a society, its proponents nearly guarantee eventual descent into fascism. The Great Transformation was published in 1944.

I had to go for a walk after that.

In Polanyi’s own text, he begins his dismantling of free market mythologies by writing that “man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships.” A market economy, by contrast, requires a society subservient to the market. It doesn’t have room for a society with other priorities—which all of them have—and by trying to force people to serve the economy above all other values and needs, free market ideologues push societies to a breaking point.

I went for another walk after reading to the end of that section because the sky was calling for admirers and there is a dizzying array of birds all over the hills along with white sage, which I haven’t seen wild in years; I went out to immerse myself in it all, and to think about those words, which articulated what many know to be true: It’s a deceptively obvious inversion of what hierarchical capitalist proponents try to claim as some kind of objective truth, that people are driven by selfish economic interests. When we know—don’t we?—that what pulls us through and along life is so much more than that. The messy, the loving, the growth and form of relationships, the birdsong and smell of lilacs, the loneliness and desire to be known, the care and mutual aid, the inefficient and creative.

Embroidery was the only useful skill I learned by the time I left Girl Scouts, aside from making a fire and baking snickerdoodles. I won’t deny that baking is a useful skill, and I have done a lot of it over the years because my kids love it, but it’s not one I enjoy. It’s too fussy and fiddly, with all the precise measuring and wondering why just a tiny bit too much vanilla throws everything off, and remembering to keep unsalted butter around. Anyway, if there’s a batch of warm chocolate chip cookies on the counter, I will eat them, with a glass of milk even though I’m allergic to milk and stuffing myself with cookies never feels good afterward. No judgment for enjoying cookies; I just can’t stop myself and end up feeling ill.

I don’t like sewing, either. I failed home economics twice purely due to sewing ineptitude. In fact, anything that requires precision is something I’ve learned to back away from. I like labor. You need a hole dug or wood sanded or rocks moved or food hunted or foraged, I’ll dig in happily. But ask me to do anything that requires a spirit level or angled measurements and I can’t take responsibility for the outcome. Every time I have ever attempted to hang a shelf or make an item of clothing from scratch, I’ve made a mess of it. I’m bad at it and, as with baking, there’s nothing about the process I enjoy.

Embroidery is another matter. Once I learned all the basic stitches and made a few potholders for grandparents and quit Girl Scouts, I stopped using patterns and started embroidering random, freeform designs of my own. Later, when I was really poor I’d get packets of cheap polyester handkerchiefs from JCPenney’s and embroider the corners to give as gifts. I did that for years until I got into making bead-and-wire jewelry, which replaced embroidery as a hobby for well over a decade, until I had kids and most hobbies went the way of a full night’s sleep and being able to linger with a hot cup of coffee in the morning.

Last year I sorted through all my handmade earrings and jewelry-making supplies and handed them over to one of my nieces. I don’t know why, but one day I realized that I’d probably never get into that hobby again. It was time to let it go. Clearing the beads and wire away somehow made me notice my sewing box with its embroidery supplies, and I had an urge to pick them up again. I hadn’t touched that box in years except to attach wayward buttons for people and some attempts to patch jeans because I’m fed up with clothes falling apart in less than a year.

When I’m in a darker mood, going for a walk is always my best answer, but since needle and embroidery thread have found their way back to my hands, I’ve been reminded of their soothing consistency. Needle in, needle out. Backstitch, backstitch, backstitch, until I run out of thread. Tease out a tangle that appeared out of nowhere. Rethread. Backstitch again. Try out a French knot. Fill something in with satin stitching.

Having some of my grandmother’s and even great-grandmother’s decorative sewing tells me little to nothing about why they did it, or why particular designs or colors. It’s knowledge and tradition that stopped abruptly, except for the action itself. They certainly never did it for economic reasons. I don’t know if they ever would have, but in the times and places they lived, it wasn’t an option.

I like part of the description that Sarah Swett gives to her newsletter The Gussett, about yarn and textiles and cordage and of course a whole lot more, like “things that want to be made.”

“Usually, the thing worth pursuing is not a thing at all, but life made manifest in color, texture, image.”

Creating things out of pleasure—things of beauty or delight, and of care, especially when made for someone else, has its own kind of lyricism, its own kind of submersion into something more than what most of us are told to care about. I like the backstitches and following whatever coiled, curled designs the needle has me do, unplanned meanderings across a piece of fabric that feel like they’re trying to say something. It’s how I write, really, and sometimes it feels like the world is too full of words for me to add any more. Sometimes it’s easier to write without them, to enliven stories through hands and fingers.

Or if not stories, then something. Something I can’t fully explain partly because I have no ancestral or cultural connection to lean on. I have no idea what I was shutting out all those years I didn’t let myself embroider, or even what I was letting in all the years I did let myself embroider for pure pleasure, nor why my paternal grandmothers made the things they did, nor what I’m drawing together or from when I use my maternal great-grandmother’s thread to make a gift for someone, and probably never will know.

Some have had these traditions and their meanings passed on to them, and some haven’t, at least not through language. Through other means, though? Through hands and embodied memory that threads its way into one’s life unarticulated? I’d like to think that could be true.

It could be life made manifest, stories and lifeways that people have been telling through decoration and craft for thousands of years. Stories that some of us pick up again even if we don’t understand why, and even when we thought the thread had snapped.

This was an embroidery gift from one of my oldest friends. It is truly one of the most beautiful things I own. It hangs above what I think of as the “creative/spiritual” side of my desk, where I look at rocks and a candle and notebook and the computer never intrudes.

What a gorgeous essay! The thoughts on embroidery are so evocative to me-- my grandmother embroidered, too, and I did when I was younger (now I knit). Her embroidery always reminded me of the song Bread and Roses-- of kindling beauty amid the grinding labor outside and inside the home.

Thanks for all of this, and especially for the beautiful shot of the sky, which comes as rare and refreshing fruit given the smoky haze here right now.

Nicely done. Glad you have the retreat time. Butte is one of those places in the world that's just a little different.

Surpised you had not run onto Karl Polanyi before. But yes, we have been warned about where we seem to be heading for a very long time. For some reason, reading that line you quote triggered a childhood memory, a time when dad got hurt on the job. I guess, feeling that moment roll through me again, that young as I was, I knew we had no safety net. It turned out better than feared. But I do not understand why we not only accept, but idolize such a harsh world.