The following is, as promised, a review of Simon Winchester’s most recent book Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World. I haven’t published a review on this newsletter before and don’t intend to make it a regular thing because I prefer to talk about books within the context of ownership, the commons, and humanity. Not that I don’t enjoy writing reviews—I do—but I avoid them for the same reason I avoid writing about feminism and misogyny: they make me full of either rage or a kind of fierce, burn-it-all-down joy, and other writers channel those feelings better than I’m able to.

I used to write book reviews for a travel website but haven’t in many years, and a long time ago decided not to write any more reviews of books I didn’t like. Land is an exception.

I’ve long admired and enjoyed Winchester’s work, from The Professor and the Madman to Calcutta to a recent essay in The American Scholar on the generosity of travel writer Jan Morris. Unfortunately, Land exposes Winchester’s persistent colonial worldview in a way that even this author of twenty- or thirty-some books can’t narrate his way out of.

While Land explores the many ways in which ownership is made possible, from surveying to cartography to imperialism, it leaves unasked the question of why humans crave land ownership in the first place. Why do societies insist on perpetuating a legal fiction that plays such a deep structural role in solidifying and widening inequality and injustice? Winchester has no answers and doesn’t seem very curious about the question.

Leaving out the initial why? creates a fundamental problem for the rest of the book. Without examining that impetus, it’s easy to gloss over the consequences of this millennia-old myth for the majority of humanity, much less for the rest of life on the planet. Winchester includes a number of stories referencing dispossession of Indigenous lands in North America and New Zealand, but the stories feel perfunctory when they should be central. He tells the facts—and very often only those—but frames them in a way that presents these histories as inevitable and, worse, Indigenous people as passive bystanders.

It is impossible to talk about private ownership of land without spending a significant amount of time on the inherent violence necessary to convert a landscape into real estate, yet somehow Winchester manages it, not only grossly simplifying complex stories of land dispossession in North America but ignoring almost the entirety of English and European land hoarding by the nobility through enforced serfdom and private enclosure of common lands.

Every review I’ve found of Land has lauded Winchester for his centering of Indigenous people worldwide. And it’s true, I think, that these stories are highlighted in a way that they seldom have been by a well-known white writer. In a way, that makes his approach all the more egregious. It makes it seem like telling the stories is enough, that no examination of the ongoing injustices needs to happen.

In Andro Linklater’s Owning the Earth—a book Winchester acknowledges as foundational for his own thinking and research—the author wrote that, “The idea of individual, exclusive ownership, not just of what can be carried or occupied, but of the immovable, near-eternal earth, has proved to be the most destructive and creative cultural force in written history.” It’s this kind of perspective that is missing from Land.

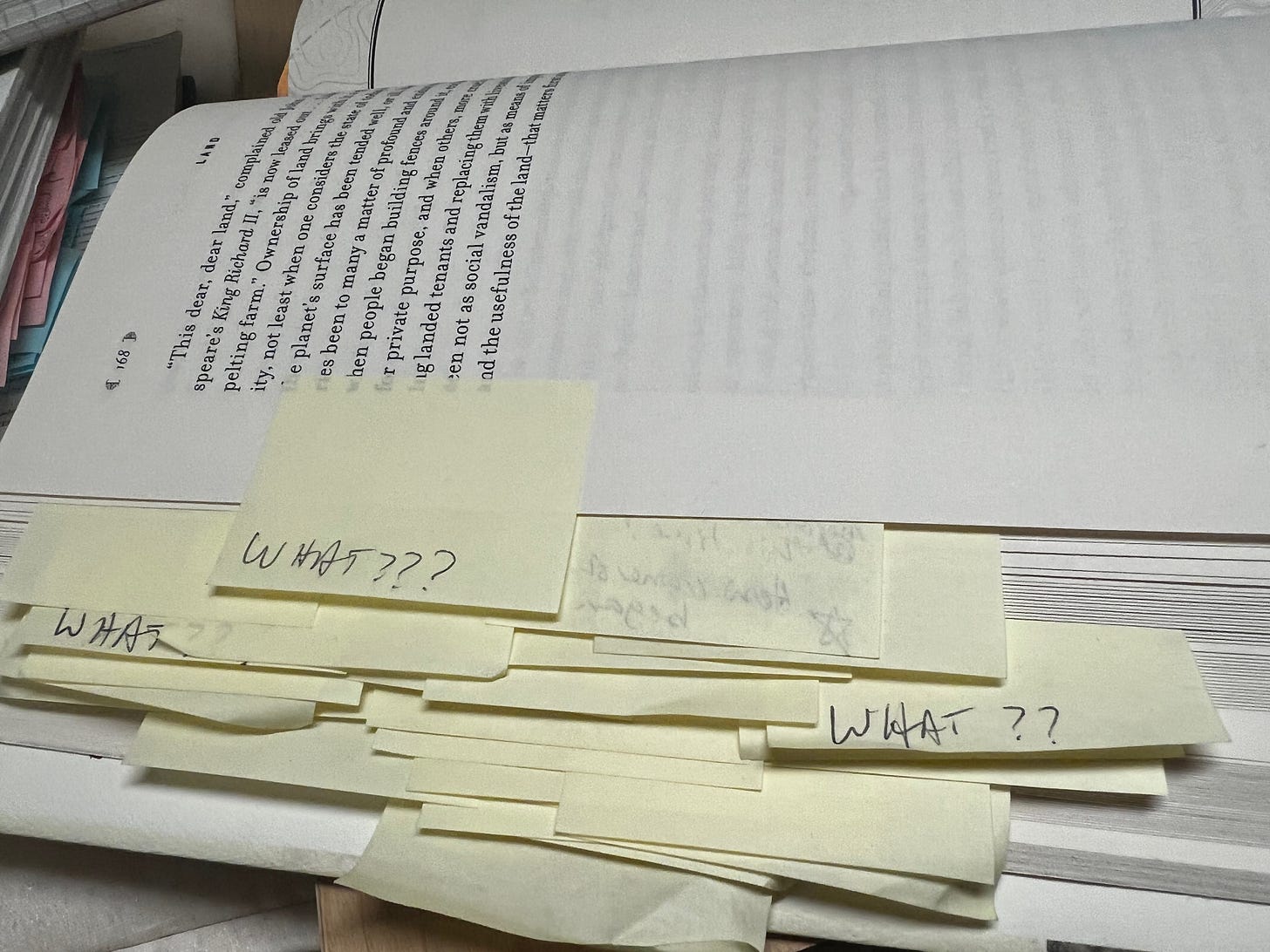

Overlooking the destructive effects of private land ownership allows Winchester to ignore his own biases, which become obvious shortly into the narrative. The book is full of phrases and words that led me to plaster it with Post-It Notes on which I wrote, simply, “WHAT???” rather than a useful note-to-self to refer to later.

The language he uses to describe people, cultures, and the process of dispossession and theft are both colonial and generalized. That’s at best. I’m trying to be generous here. Winchester’s finest and most detailed writing is saved for measuring, dredging, and building, the engineering- and thing-centered subjects that he has excelled at in previous books. Dispossession, theft, and colonization are treated with a few broad strokes and more than a few stereotypes. Again, that’s at best. By page 18, I was already sending snippets to a few writer friends to see if my outrage at Winchester’s perspective was over the top:

“The relict Schaghticoke did not merely leave, however, but clung on in the naïve hope that one day, treaties would be honored and promises kept. But they never were; and today the rump of the tribe, with a few hundred others scattered wide and bickering among themselves, are reduced to living in a cluster of shacks on the flood-prone banks of the Housatonic, constantly in and out of court, pressing in vain their claims for land long ago given to a local school and the state power company.”

Relict. Naïve. Rump of the tribe. Reduced to living. Almost every bump of every sentence in this passage—and it continues for another two-thirds of a paragraph—is nailed with language that dehumanizes and demeans, and more than that, it and other passages get hammered down in absolute ignorance of history. Is it naïve to trust that a government will honor its treaty obligations? One could argue that perspective in the case of the United States (why not write, then, about how egregiously treacherous and shitty that is, about a government so dishonorable and thieving that it’s naïve to trust it? Why skip right over that part?), but even if it is, that isn’t what happened. There is plenty of scholarship out there detailing the ways in which Native American nations fought for land and people—legally, politically, diplomatically, and physically—but Winchester fails to make the slightest effort to question his own assumptions. Nor does he seem to have any knowledge of the Landback movement, which was hardly new when he would have been writing this book. Why can’t the local school and the state power company return the land? It doesn’t occur to him to ask.

Recent books such as Nick Estes’s Our History Is the Future have skillfully laid out the betrayals of the U.S. government in particular and white European colonizers in general whose “success” in “settling” North America consisted of killing off as many Indigenous people as possible whether through disease or massacre; repeatedly refusing to honor treaties that the government itself had insisted that Native nations agree to; and, when nations refused to give up land that was meant to be solely theirs by treaty right, took their children away and sent them to boarding schools until they complied. There is nothing naïve in any of this.

No matter how sympathetic his perspective, Winchester never manages to write about Indigenous people as anything more than passive observers of history. Repeated use of the world “bewildered” leaves the impression that Native people have been confused, innocent, placid, and, again, naïve. The Sioux leaders were “bewildered” during 1858 treaty negotiations, and the reservation today “forlornly advertises itself as ‘the Land of the Friendly People of the Seven Council Fires of 1858.’” Forlornly advertises. A colonial viewpoint if there ever was one.

Colonial remains Winchester’s worldview. There’s a bare smidgeon of consolation in the fact that he uses similar characterizations for tenant farmers forced off of lands in Scotland during the Highland Clearances. The Clearances were born from the enclosure movement that started centuries ago and stole the commons from the people of England; they were their own iteration of colonialism:

“Lord Stafford, as he was then still known, forcibly and cruelly removed thousands of crofters from their pitiful smallholdings and settled them, mulish and unwilling, scores of miles away from home.”

Pitiful. Mulish and unwilling.

I’ve worked with words almost my whole life—certainly all of my professional life. Being a copy editor is in some unexpected ways akin to being a poet, only in that the precision of language matters a great deal. In my own writing, I’ll sometimes stare out a window or go for a walk in search of the right word; when I’m copy editing, I do this even more frequently. I feel for the textures of words. Their nuances and the underlying metaphors. What they mean to say. What world does this word hold? is a question my copy editor self carries with her constantly.

Winchester has been a professional writer for decades at this point. He knows how to tell a story and his books are generally fun to read. He doesn’t, as far as I’ve seen, narrate in a haphazard fashion. He’s most famous for The Professor and the Madman, which is in itself a book about how much meaning any given word can hold. I don’t think he intends to be demeaning, but everything about his approach in Land is a choice that reflects how he sees the world, and that includes how he writes about people.

These choices are made worse by the fact that Winchester doesn’t seem to have interviewed a single Indigenous person for this book, and with perhaps one exception (quoting Harvard professor Philip Deloria on land-stealing treaties) failed to write any of these stories from a non-colonial perspective. I have a hard time believing, for example, that this passage would find widespread agreement even among bog-standard university historians:

“The Native Americans whose lands these once were have not forgotten, nor probably ever will. But such anger as they might justly feel has long ago ebbed, and it just simmers in the far background. The notion that the United States could ever have had the effrontery to call these acres ‘unassigned,’ when in truth the republic never possessed the moral authority either to assign or unassign them, here or anywhere else, is mostly forgotten today. The world has moved on.”

[Me on a Post-It for the umpteenth time: WHAT???]

Winchester published these lines despite the fact that the 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma U.S. Supreme Court decision essentially restored 1866 treaty boundaries and reaffirmed the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s sovereignty over tribal members on that land. (This decision was appealed yet again and has found a court more friendly to continued settler-colonialism.) While the decision likely would have come after Land was already in the editing process, the case was originally heard in the Tenth Circuit in 2017 and the Supreme Court agreed to an appeal petition in December 2019. Since he had a whole chapter on the colonization of Oklahoma, he’d almost have had to work at not knowing about the case while writing this book.

To say that land dispossession had been “largely forgotten” is simply untrue. While many people might have been unaware of these cases or the issues at stake, Native nations certainly haven’t been. And they are central to anyone purporting to write authoritatively about land ownership in North America. To overlook them is simply sloppy research.

Should I give Winchester more credit for at least trying? Maybe. But every time he writes about these histories, his tone is patronizing and he seems uncomfortable. In the passage on Francis Drake landing in (probably) what is now northern California, Winchester clearly wants to frame Drake’s claiming of the “whole land unto her Majesties keeping” as an injustice inflicted on the Miwok nation. Yet that history is briefly covered in a few lines. He spends a great deal more time and detail on the queen’s knighting of Drake in 1580. It’s in describing Drake’s ship and voyage and knighting where his language flows. When he writes about the actual consequences of these actions and choices, he reminds me of me when I was writing the robotics sections of my book on walking: pained.

I write a lot about being compassionate and kind—yet another reason why I don’t like to write book reviews anymore—but I write about those because I struggle so much with them. Truthfully, I am tired to the core of giving people with enormous privilege credit for simply trying. Try harder.

The effect of reading Land is at best one of psychological whiplash. His research, while extensive in the realm of cartography, overlooks, for example, the significance of the 1823 U.S. Supreme Court decision Johnson v. M’Intosh, which stated among other things that:

“Not only has the practice of all civilized nations been in conformity with this doctrine,* but the whole theory of their titles to lands in America, rests upon the hypothesis, that the Indians had no right of soil as sovereign, independent states. Discovery is the foundation of title.”

* The Doctrine of Discovery comes from the 1454 and 1493 papal declarations that gave right of ownership over land, resources, and people to European Christians who “discovered” them

Not only did Johnson v. M’Intosh state that Europeans have title by automatic right to all North American land due to discovery; it also stated that, since Native nations supposedly had no concept of private ownership, they could never have been qualified to hold property title in the first place. This second declaration is a circular and self-referential decision that made white settler ownership of land a fait accompli no matter which way you looked at it.

More recent cases, too, such as City of Sherill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, which was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005, used the Doctrine of Discovery to decide that the Oneida Nation could no longer claim sovereignty over land it had legally purchased on the open market:

“Under the ‘doctrine of discovery,’ . . . ‘fee title to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign—first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States.’”

In other words, the Oneida Nation could buy the land, but not claim sovereignty over it. That decision was written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, which is why, as much as I respect her work and legacy, I’m not a total fan. (The Indigenous Values Initiative has a good explainer of this case.) These cases and their lasting consequences matter tremendously in the question of land ownership. They show its foundations to be full of rot and racism, but Winchester doesn’t go anywhere near them.

All of this is before we even get to his failure to address what is purportedly the topic of the book: land ownership itself.

Winchester barely touches land ownership’s genesis. He claims at one point that ownership in England began “with the lines of furrows left behind by the ploughs of neighbors, probably fourteen hundred years before the birth of Christ.” Which is, not to put too fine a point on it, ludicrous. Maybe this was how a form of ownership was practiced, but it’s just as likely that a form of commons land-sharing was in play, as it has been all over the world and for which there is plenty of research that Winchester doesn’t seem to care to glance at. Even though, again, he credits Linklater’s Owning the Earth, which is entirely about how land has been shared and how private land ownership destroyed various systems of commoning worldwide.

Land is a mess of a book. Which is a pity. It covers a lot of important and widely neglected histories, like the forced collectivization of farms in Ukraine under Stalin’s Soviet Union, which led to the starvation of millions in what is known as the Holodomor. It delves into how Americans of Japanese descent left the U.S.’s concentration camps after World War II to find that white people had stolen their land and businesses. It unfolds the destruction of vast areas like the Marshall Islands in the 1950s, sacrificed to the U.S.’s nuclear weapons program.

These stories are important, and I’m glad Winchester wrote about them. That doesn’t erase the fact that too much of this book is written by a man stuck in time, in a mindset and worldview that his words can’t hide. Maybe I should be more generous. But what I take from this book is instead a reminder to myself: Try harder.

In Our History Is the Future, Nick Estes makes the firm and repeated point that massacres, thefts, and betrayals of treaty obligations had one aim: to turn land into private property. The heart of ownership is that something is mine—not yours and most certainly not ours. This process isn’t accomplished, as Winchester seems to wish, by interesting endeavors to measure the planet or map geographical contours. It’s accomplished with violence. To gloss over that in a book on ownership, in this day and age, is unacceptable.

Two more gripes:

I am utterly confused by Winchester’s lines in a paragraph promoting pre-Colombian American culture and civilization: “Native Americans are all, it should be remembered, genetically related to those who twenty thousand years ago crossed by way of Beringia, the land bridge across the north Pacific between eastern Russia and western Alaska. Native Americans are, genetically, a Pacific people. They are, in essence, an Asian people.” First off, did he talk to a single Native American person about this? And secondly, try as I might, I can’t find a way to read this entire passage as anything other than Winchester saying, “These people must be civilized because they’re Asian.”

I would also like to take issue with his statement that, “No American, so far as I am aware, ever professed a deep and unsullied affection for the USGS topographical sheets that it is possible to order from the government agencies.” I’ve written about my own childhood obsession with my mother’s collection of topo maps in several places, I think even in my book about walking somewhere. I’m sure I’m not the only American who has a deep affection for those maps. Maybe, as with so many things in this book, he didn’t bother to ask.

Fuck this guy. I can assure him my rage has not "long ago ebbed" and it absolutely does not just simmer "in the far background."

I'm done with white historians. Absolutely done. Done with white dudes writing anything. Done, done, done.

I'm so glad you took the time to review this book. As much as I, too, hate to bash books, sometimes you just have to speak up. I'm glad you did. I'll try better, too.