Audio version:

Imagine yourself in a cabin, curled up on a beaten couch in the corner of the small room shared by a couple of bunk beds, a table, a counter and stove, and you. It’s night out, and an almost-full Moon was rising in the south when you went out earlier, a boreal owl barely audible from the woods.

The propane-fueled fireplace is warm but doesn’t give off quite enough light to read by. But you sink into the pages anyway, take them slowly because you’re in that kind of mood. You watched a whole flock of bluebirds for an hour earlier, and as you drove up to the cabin, a bald eagle flew overhead. There are no people nearby. You are fed and tired and ready for bed; to slip into it via firelit poetry feels perfect.

As you turn the pages, something happens, a quiet internal earthquake. It’s not one particular poem or line or turn of phrase, but the accumulated effect of their weight: quiet and light, like snowflakes, carrying that same balance of power and delicate beauty. The poems each strip away a layer of something, you’re not even sure what, and by the end of it you look up at the flames slightly irritating in their gas-powered sameness and think, That’s where I’ve been hiding.

A few hours earlier, I’d been standing by the side of the road watching bluebirds. I have never seen so many bluebirds in one place. At most I see one or two of them a year, their impossible bright colors a flash of delight. There were at least ten, maybe fifteen, flying among last year’s grasses, barely pausing on the dry branches waving in the wind. I truly could not believe my eyes. At the far end of the field, a couple of elk romped together among their herd, and snow-clung mountain peaks stopped up the horizon like a postcard for Montana.

My feet ached to wander into that field, wiggle toes into the soil that could draw so many bluebirds.

My friend

and I were talking recently about the ease I feel when letting my feet rest in running water, the concept another friend had proposed of feeling “grounded in flow.” Maybe, Amanda wondered to me, you pray through your feet. That idea tasted like a fresh wild huckleberry on a hot hike when I’ve run out of water, reminding me of something from Eddie Benton-Banai, that “to live an Anishinaabe life is to live one where every footstep is a prayer” and the fact I sometimes forget, that I’ve spent years now devoting my professional and personal life to walking this world and relating to it as deeply as possible. The more I do it, the more I want to do it.Which is how I ended up writing about ownership, private property, and the commons in the first place. Because too many places I yearn to walk, like that field of bluebirds and elk, are inaccessible not due to terrain or danger, but to the simple fiction of ownership.

It’s a friendly No Trespassing sign, the orange almost cheerful, the font relatively friendly, and no hint of being shot at—far too common in Montana—for crossing the barrier, but it’s a barrier nevertheless.

In his book Enlivenment, the German philosopher Andreas Weber writes of the enclosures of the commons throughout Europe as not just a denial of physical sustenance and survival, but of a spiritual severing. Enclosures and the rise of the market economy

“not only governed the allocation of land, but also redistributed the spaces of our consciousness. In reality, the forced separation between that which gave life (the biosphere) and those who were gifted by life (the commoners) was an act of violence on the part of the landlord, who excluded members of the ecosystem from their rightful positions and thereby damaged these participants, the ecosystem itself, and the unifying experience of self-organizing coherence.”

Commons, Weber had written earlier, is a system in which there are no users or resources, “but only diverse participants in a fertile system, which they treat in accordance with a higher goal: that it continue to give life.”

When the land was no longer commoned, when it was stolen for the purposes of private ownership, it could also no longer be related to. People were denied access to that most fundamental yearning, to relate to the land we live with. Their minds were bent, by force—the number of bloody rebellions against enclosures of the commons might be surprising to those who assume private property came about naturally—to see themselves as separate from nature, disconnected from land and a living world, and able to survive only by working for someone else—the genesis, commons scholar Peter Linebaugh has said, “of the j-o-b.”

We know how well all of that has turned out.

Dismantling the story behind private land ownership, and exposing the lack of foundation for laws defending it, is necessary to finding a way out of it. But so is restoring a shared relationship with all of life. I wanted to walk that field because I am alive and the field is alive and the bluebirds were so beautiful I wanted to cry and it means something to know that, and to know it’s true and right to feel that way, even if the No Trespassing signs stop me acting on it.

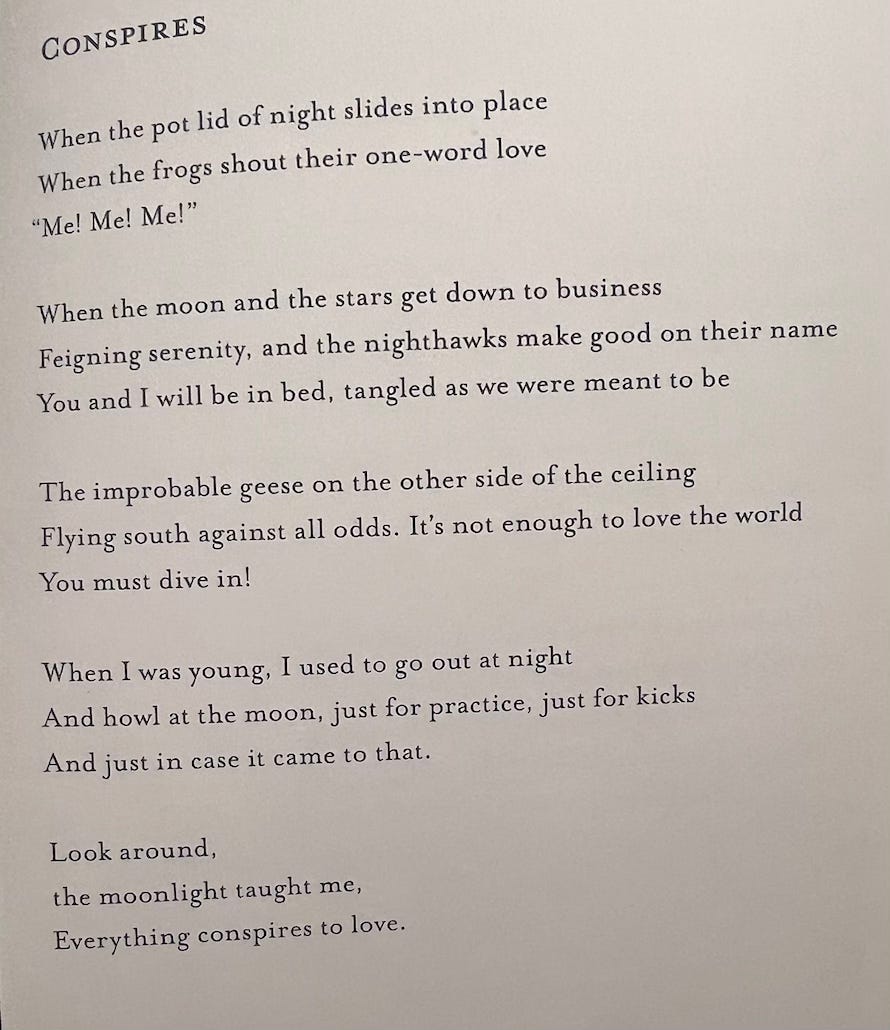

The book I read that first night at the cabin was by someone I was fortunate to meet recently, poet, essayist, and woodworker Charles Finn. He’d generously given me a copy of each of his books: Wild Delicate Seconds, a book of short essays, and On a Benediction of Wind, a collaboration between Finn’s poetry and the black and white photography of Barbara Michelman.

It’s tempting to spend the rest of this space quoting numerous lines that I keep going back to, like

“Above the geese the soft colors of the afternoon deepen into a tremendous wound and a gibbous moon is birthed, shadows crawling over the snow to dissolve into the river”

from Wild Delicate Seconds, but like most reading for pleasure and insight, how anyone receives those passages will be personal to them. There’s a quiet reverence for the world that invites rather than demands the reader’s attention, both to the writing and to the lives it honors. I read On a Benediction of Wind all in one sitting that first night, which I don’t think I’ve ever done with a book of poetry, and at the end I closed it and stared at the fire and went out to visit with Moon and felt, for the first time in a long time, a steadied feeling of being at home—in the world, and in myself.

The next day I chose a trailhead at random and walked barefoot for two miles on dry pine needles along a waterlogged trail, the nearby river free to stretch herself over the ground. I spent hours by the lake after gasping into its snowmelt cold, watching the waterfall far across the valley, crashing snow from its mountains’ embrace through a ravine and brushing into my dripping hair snowmelt and sunshine, a wolf’s nose nudging a track, a wolverine’s strand of fur, the promise of berries still sleeping, and the call of the loon diving under spring’s early waves.

“Conspires,” from On a Benediction of Wind

I really loved this Antonia. After leaving an abusive church over a decade ago, I started walk in the mountains here in Northern Ireland. At the time I had no words for my heartache, so I let my feet on the earth speak for me. Footstep after footstep, hike after hike bringing healing and a relationship with the land and the divine. It has been the greatest teacher and joy of my life and had brought me back to my wild self. Thank you for this wonderful piece that spoke to my heart, I especially loved reading about you brushing snowmelt and sunshine into your hair... so beautiful.

I wrote about the myth of land ownership not too long ago. I found the connection between enclosures and the witch hunts very compelling. Many outspoken elderly women were displaced at that time and ended up being tried as witches as a means of getting rid of them.