Audio: I’ve had a few conversations recently with friends who are having trouble reading. Even I’ve found myself reading far fewer books this year. Maybe it’s burnout, maybe it’s the internet, maybe it’s Covid. I have no idea. But I’m trying something I’ve been wanting to include for a while here, which is reading these essays aloud for anyone who’d rather listen than read. I can’t promise to do it every time, but I’m going to try.

Thank you for being here! It makes a difference. Paid support has recently helped make possible a research trip that covered hundreds of miles and many hours in the genealogy and local history sections of a small-town library, and disconcerting time with a haunted doll. The research is making it into No Trespassing and a separate big essay project on private property; the haunted doll I hope won’t (I did put a picture of her in the Chat).

Earlier this week I was walking my nieces over to my house when it was still dark. We got shoes and coats on and checked to make sure their lunch bags were in their backpacks, even though I’d watched their dad pack everything before he left for work. We locked their house and I paused to breathe in the cool early-morning air that I can never get enough of, and glanced up at the sky. It had been overcast for days but that morning was dark-bright clear, the stars speaking of both distant galaxies and ancient cosmology stories.

“Look!” I said, pointing up, “there’s Venus!” They were so excited as I told them how that bright star-point was actually a planet hovering high in the southeast. Then we found Jupiter, almost as bright and a little lower in the west.

It’s one of the things I’m most grateful for about where I live, that we can still see the stars. The light pollution continues to grow, and it’s nothing like being at a cabin or camping, but when I take my first step outside between four and five in the morning, I can, if it’s not cloudy and there’s no moonlight and I let my eyes adjust for long enough, trace out the path of the Milky Way, and am often rewarded for patience with a shooting star, which never fails to feel magical.

Last night as I went to bed, Moon was out low in the southwest, looking almost like a Harvest Moon, all big and golden and bright even though She’s only in Her waxing crescent phase, not even a quarter full. I wonder what it feels like to Her, when She’s only partially sunlit but all of that side is still washed in a golden glow. Does She feel Her own beauty? Does She ever wonder how many of us are taking the time to let our eyes linger on Her light?

In the evenings, my younger kid and I often go outside if Moon happens to be visible before I go to bed, and we watch Her together. They took immediately to the Anishinaabe teaching of Moon is Grandmother, and together we speak of Her that way. Maybe I’ll ask them, or my nieces, who see the brightness of Venus with such fresh, starstruck eyes, what Moon might be thinking.

It delights me to no end to see how easily children’s attention is directed to the world they instinctively love. We all start out that way, loving the world and attending to it.

This last June, I received a gift from one of my neighbors: a small handful of sweetgrass starts. I’ve been interested in growing sweetgrass ever since moving here and being told by a mutual friend all about this neighbor and his relationship with ceremonial sweetgrass.

He can be a hard person to catch, but last winter I ran into him plowing his driveway while I was walking the dog. After we’d chatted a bit about the winter’s extreme weather fluctuations that saw days of -40°F winds and frozen snow followed by days of rain, I told him that I’d really love to learn how to grow sweetgrass if he’d be willing to teach me.

When I walked down to his place in June and said I was still interested, he introduced me to the sweetgrass bed in his yard. We talked about how to tell the difference between sweetgrass and quack grass—not easy but a necessity because quack grass grows everywhere here—and he showed me how to harvest and dry the grasses. Then he gently pulled a few roots out of the ground so I could start a patch in my garden.

“Sweetgrass is friendly,” he told me, “but likes respect. And it likes to be alone,” as in, not mixed in with a bunch of other plants.

I can relate to all of that, I thought.

I planted her in a bed she could have all on her own. Almost every morning since then, I’ve gone out and talked with her at least briefly, unless I’m away, one of the small stitches of early-morning ritual that includes looking at the stars and Moon and then writing by candlelight before getting people up for school, which I use to connect with the world and also keep myself from unraveling.

Since my neighbor gifted me those plants, I’ve thought a lot about the kind of respect they like, about respect in general, respect and recognition and what we give attention to: people, beings, things. How we attend to this world. It brought me back to why I wrote A Walking Life and why I’ve devoted so much of my time and energy to living it.

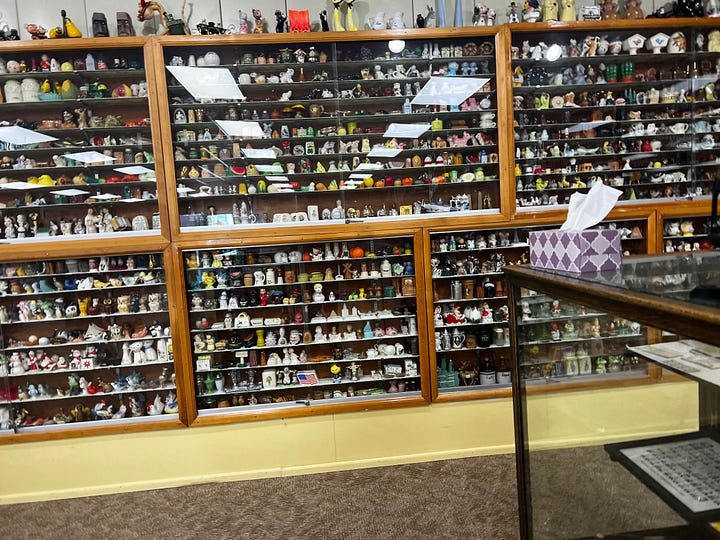

Last week I was in Great Falls, Montana, as part of a research trip that also took me through Lewistown and Raynesford, and included a side jaunt to Stanford to see if the Judith Basin County Museum does indeed have over 2000 salt and pepper shaker sets. (It does. People are weird.)

There was a talk being given while I was in Great Falls that I wanted to attend, and I had to make a choice between a 7-minute drive or walking, which would take around an hour and fifteen minutes. As I often do, I grumbled with myself about the walk. It’s not a pretty one. It’s along very busy roads with few trees, and there is no sidewalk or road shoulder for a good chunk of it, which is always a reminder of how much of a risk walking places can be. But I knew that unless I got really caught up in my writing and worked until the last minute, I’d walk.

Every time I do this, I’m reminded of why it’s so important that people get out of our cars and start walking places, when there’s time and opportunity, or maybe especially if you have to make time and opportunity. If it’s not easy, if it takes effort. Because it shouldn’t be that way but it is, and you can’t see where walking is made difficult if you don’t do it yourself, which means that you can remain ignorant of the needs of those who can’t or don’t drive. In the U.S., that’s around a little over 30% of the driving-eligible population. Advocating for walkability and public transportation sounds boring and policy-wonky to most people, and it can take a lot more dedication than higher-profile causes, but if we want a planet livable for humans, much less the rest of life, shifting away from individual cars and toward walking and public transit would make more of a difference than almost any other change we need to make.

A car-centric culture makes it easy to wrap ourselves in a perception of the world as existing for our own comfort and ease, never existing for its own sake. I put 850 miles on my car last week doing research, and I don’t think that’s a thing to be proud of, even if I enjoyed many hours of driving by myself on mostly unpopulated roads through landscapes I love. If you can’t walk or take public transportation places—if there’s no choice—it’s a good starting point to ask why that’s the case and what you can do about it.

And there’s much you don’t notice when you’re in a car, much that will never catch your wandering attention. If I hadn’t taken that hour-plus walk in Great Falls along unpleasantly busy roads with mostly too-narrow sidewalks until there was no sidewalk left, I might never have seen the beautifully colorful mural of buffalos painted along the walls of an underpass* dominated by racing traffic. Or the nonfunctioning payphone (I checked; no dial tone) still sitting against the building of a business that looks closed at first glance but I think might be . . . I have no idea, actually. I spent a while trying to figure out what it was, which made me late for where I was going, but it remained a curiosity.

Or the fact that all along this busy, traffic-choked route were ditches full of broken bottles and plastic bags and cans and other trash, and in all of them grew patches of short perennial sunflowers. I was so delighted seeing their bobbing yellow heads each time that I forgot to take pictures.

There is so much in the world to give our attention to. But because walking has been so effectively built out of our daily lives, doing so requires intention. It requires us to make choices.

This week I finally cut a few strands of sweetgrass, dried them, and got in touch with my neighbor to learn what to do next. He rode his bike over to my yard and we went through the small handful together, pulling out a few more bits of quack grass. He tapped the short blades together, braiding them deftly but not so quickly I couldn’t follow. “Not too tight,” he said, “or it won’t burn well.”

He showed me how to pull-knot the end and handed the braid back to me. There are so many gifts in that one bundle, from his sharing of plants to his sharing of knowledge, that I felt overwhelmed. It felt right, to feel overwhelmed.

If I want to give sweetgrass the respect it should have, I have to go through each blade, one by one, to pull out the quack grass that’s mixed in. It’s not easy. The differences between the two plants are subtle, and even sorting the small handful I harvested took a lot of time.

It feels like worthwhile work. Why not give close, caring attention to that which matters to us? Trying to turn myself into a carer of sweetgrass reminds me of walking itself, of all the reasons I wrote A Walking Life in the first place and why I realized I’d have to live what I preached in it: because all the world needs our attention and care, and an essential element in getting there is re-finding our own places as embodied, living creatures in this life-filled world. Walking, like plants, like life, shouldn’t be relegated to wilderness areas or even parks—all places I love to spend time in but almost all of which require an automobile to get to. The very tools we use to “access nature” are directly complicit in making existence so difficult and tenuous for all of life. Why should any of us assume the world right in front of us, broken as the dominant culture has tried to make it, is less worthy of attention?

The bed I cleaned out for the sweetgrass already has quack grass creeping in. That will never end. Quack grass is ubiquitous here, very friendly, and seems to have no interest in being alone. That doesn’t mean I should give up growing the sweetgrass, or give up hoping I can someday know her well enough to make gifts from her, and to teach my younger kid to do the same. All it means is that my full attention is required to nurture something beautiful and honorable and worthy.

Life asks us, constantly, to take a little more time, make a little more effort, give a little more attention. Not just for the rest of life’s sake, but for humans’ own. Everything we do to reconnect ourselves to the rest of the living world, whether it’s watching moonlight in the early hours, teaching children to look for Venus and read the rest of the night sky, walking places whenever we can and with as much of our present selves as possible, or giving plants the respect and attention they need to thrive, is one step closer to bringing us back to life.

After we talked more about growing, harvesting and braiding methods, my neighbor asked if I wanted some more sweetgrass to braid. He had a bunch ready to harvest and wouldn’t be able to get to it before winter. He came back with an armful, which was so fragrant it made me want to sink into her sweetness (the scent is commonly described as being “vanilla-like” but to me it smells of spring’s first apple blossoms), and I gave him a jar of chokecherry jelly, which is my own longstanding gift to people. It turned out it was his favorite.

I laid the grasses out on pans to dry in the sun and thought about how many more hours it would take to go through them one by one before I even got close to the point of making a braid. So much work, so much attention, and so much a gift to be able to do any of it.

*I looked it up later, and Great Falls has a Mural Walking Tour you can embark on. The mural I wrote of here is the First Avenue North Underpass Mural, near the old Milwaukee Railroad Station.

So much in this to respond to but my mind is stuck on this phrase “It’s along very busy roads with few trees, and there is no sidewalk or road shoulder for a good chunk of it, which is always a reminder of how much of a risk walking places can be”

It reminds me of what a privilege it is to be able to walk peacefully where you live. I find it extremely difficult to take a walk in spaces around my apartment. However, when I go to the countryside, all I ever do is walk and take in the little details of my surroundings. I love to walk, but I really cannot do it inside cities as I am always afraid of being ran over by rash drivers. This makes me especially paranoid about the safety of children and pets. I never let my cats out; poor things only get to watch birds and squirrels from the windows. As you suggested, it is perhaps time to ask why it is this way and what can be done to fix it!

Another wonderful essay. Thank you Antonia.

I love the sky this time of year, especially during the winter months. My first 5 a.m. and my last 10 p.m. chores each day are feeding the horses. I give each horse their hay and as they settle to eat, I pick one of the horses, and leaning across his warm back I watch the constellations move across the sky. I'm so grateful for the dark, the quiet, the cold, the glorious star-filled sky and for my presence to enjoy and love all of it.