Where time and attention remain whole

Essay (about time and silence that turned into one about caregiving that turned into something about capitalism that turned into time and silence again . . . apologies for the inconvenience)

5% of last quarter’s revenue from On the Commons went to FAST Blackfeet. Next quarter’s 5% will go to All Nations Health Center. I encourage everyone to support similar organizations and initiatives, however you can, wherever you are.

During my most recent stay at a Forest Service cabin in early March, I thought off and on about time and silence. Most of the cabins I stay at are out of cell phone range, have no electricity (some do, but otherwise are heated and lit by propane), no internet, are limited to a stay of three nights, and are out of the way of people and traffic and most other noise. When I’m there, the silence is tangible and my sense of time changes drastically.

I go to these cabins partly because I continuously crave being alone, and partly (mostly) because I’m able to get so much more work done there. At home, the amount of work time available on a daily basis is almost laughably limited. Most of my days end up dissipated by dust devils of commitments. I’m constantly paring them back, but something always comes in to replace them, even if it’s just a stomach bug or bad head cold my kids brought home from school.

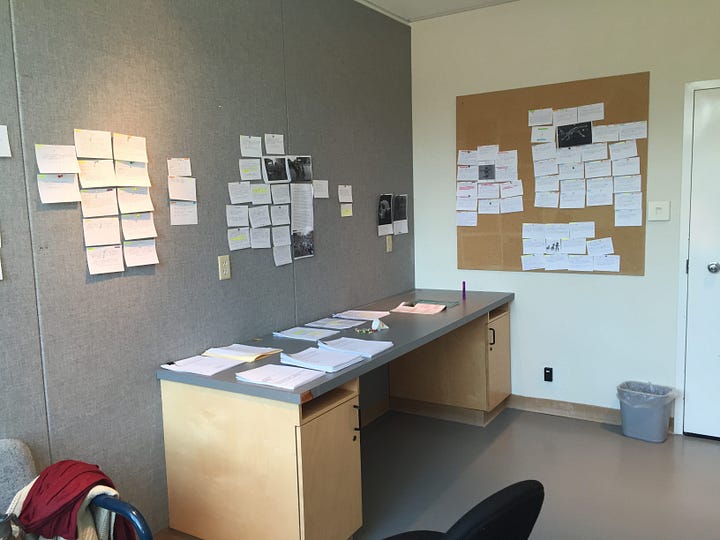

These time-ravenous commitments aren’t new, though they wax and wane. When I was writing my book about walking, my kids were very little and my younger sister’s family, including a toddler and a newborn, were living with us in a small house. My work space was a desk in the short, open hallway outside of my kids’ shared room. Some months into the project, I broke down and spent several days hiding myself away in tears. I had a book contract, a comparatively decent advance, and a great editor, but there was simply no way I had the time or space to do the kind of deep thinking and writing the book needed and deserved. Caregivers don’t get to write books, I thought over and over. I got through it, but couldn’t stop thinking that if writing a book was that difficult for me, it would be so much harder for many other people.

The daily circumstances that led to that minor breakdown paralleled how I’d told my publisher I wanted to approach the subject of walking. It’s how I approach a lot of issues and struggles, whether they’re mine or my community’s or the world’s, by asking one question: What are the barriers? What I lacked was something I’d craved ever since having a baby but really most of my life: time and mental quiet.

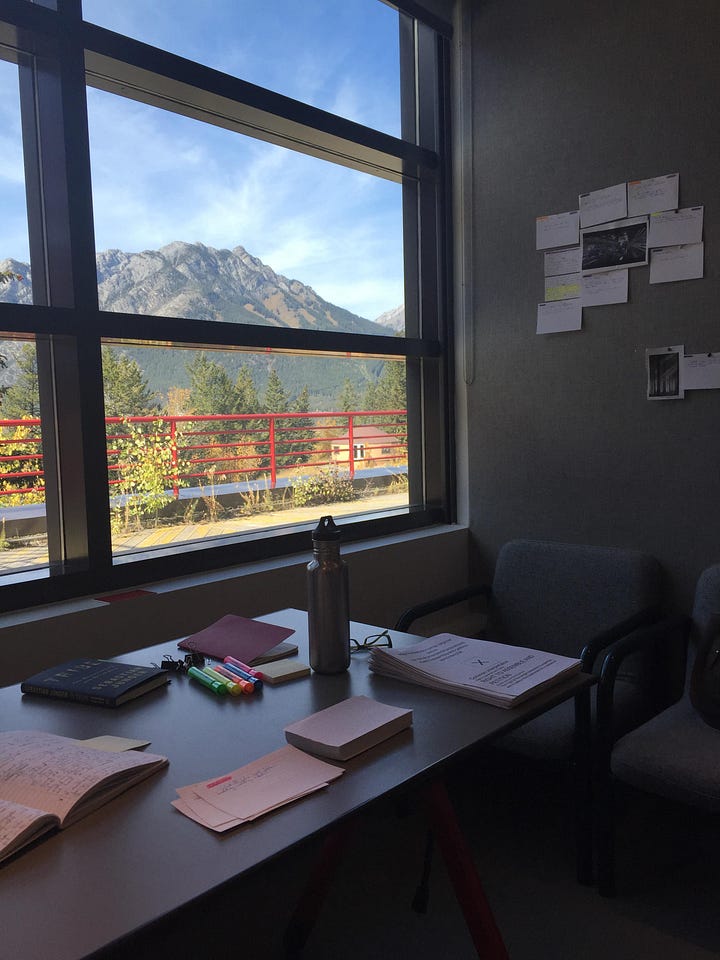

I started reserving myself U.S. Forest Service cabins once or twice a year only a couple of years ago. The weeks-long writing residencies I’d been to were productive and even fun, but expensive, and I found that almost inescapable socializing swallowed a lot of residency hours I couldn’t afford to lose. (There is a hilarious passage about this seemingly universal aspect of writing residencies in Martha Grimes’s novel Foul Matter. It makes me laugh hard every time I read it.) I just needed time, and my mind to myself. A place where hours and attention weren’t chopped into little pieces.

That first cabin stay, which was only for two nights, I was astonished at how much I got done. Same for the second. The third reservation I gave up because of a copy editing deadline. That was in Covid’s second autumn, when I was trying not to be bitter about humanity, and was so ground down by homeschooling for the second school year in a row, my days looking a lot like they had when my kids were tiny—dictated by meals and cleanup and meltdowns and a momentary rhythm of math and reading and music practice in the mornings—that I’d become less a thinking person than a mass of rage and despair fed by potato chips, beer, and gummy bears.

None of these getaways have been easy. Without intending to, I somehow started out motherhood as a full-time stay-at-home parent who worked late at night and early in the morning and spent all day caregiving. I’d never wanted to be a stay-at-home mom (and have also come to loathe the word “mom”; a friend said recently it feels loaded with societal expectations of a narrow, fixed identity that disallows any other sense of self, and I feel that very much), but fell into it due to a number of factors, including our first baby’s nearly eight-week prematurity and month-long stay in the hospital’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, the fact that I’d worked freelance from home for years, and my spouse’s job, which required him to travel more than half the time. And the reality that childcare in the U.S. is outrageously, horrifyingly expensive.

So when I needed to travel somewhere to research my book, or wanted to go away to a writing residency or conference, the logistical maneuvering was intense and exhausting. When my spouse travels for work, he packs, picks up his passport, and goes. But I’m the primary caregiver. When I go away, I put in days of arranging or rearranging appointments, checking on homework or long-term projects and other activities, making sure rides to anywhere needed are taken care of, touching base with everyone’s mental health, making sure everyone’s caught up on laundry and has showered recently . . . I won’t go on. If you know this routine, and its reverse when you return home, I bet you feel it in your bones. If you don’t know it, I’m not sure I can help you feel it. It was something my spouse and I fell into rather than consciously chose, but restructuring it has proven more difficult than I’d imagined. Covid brought an immediate stop to the business travel and it mostly hasn’t returned, which helps.

Last summer was the first time I went away somewhere offline and out of service and just . . . went. It was August, so there was no school to worry about, but my kids are also getting old enough to not need me so much. So when I got a week’s notice that I was off the waitlist for a two-day wilderness trail crew, I filled up the gargantuan gas tank of my ancient truck and watched the gauge visibly drop as I drove to a trailhead near the Continental Divide.

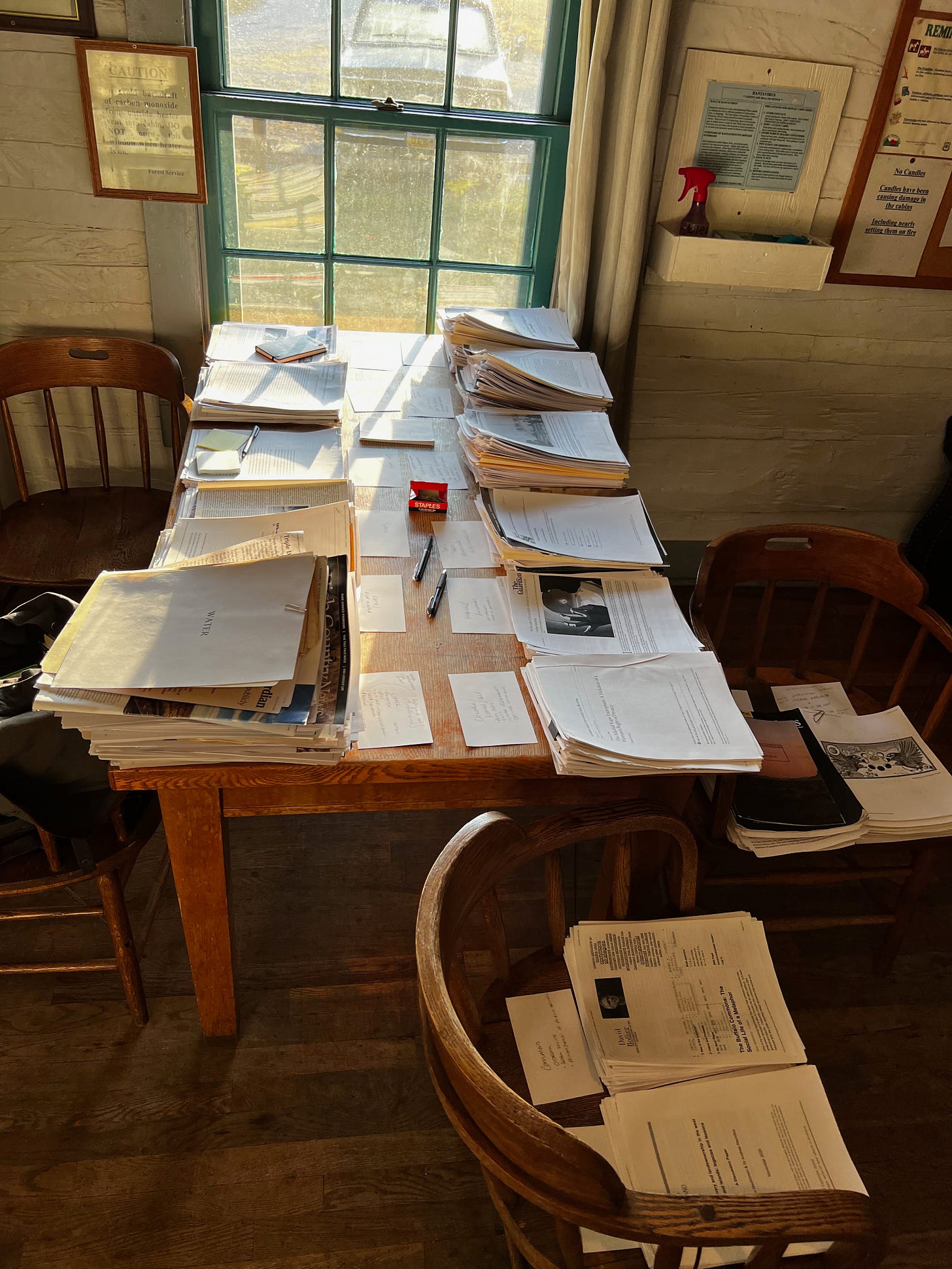

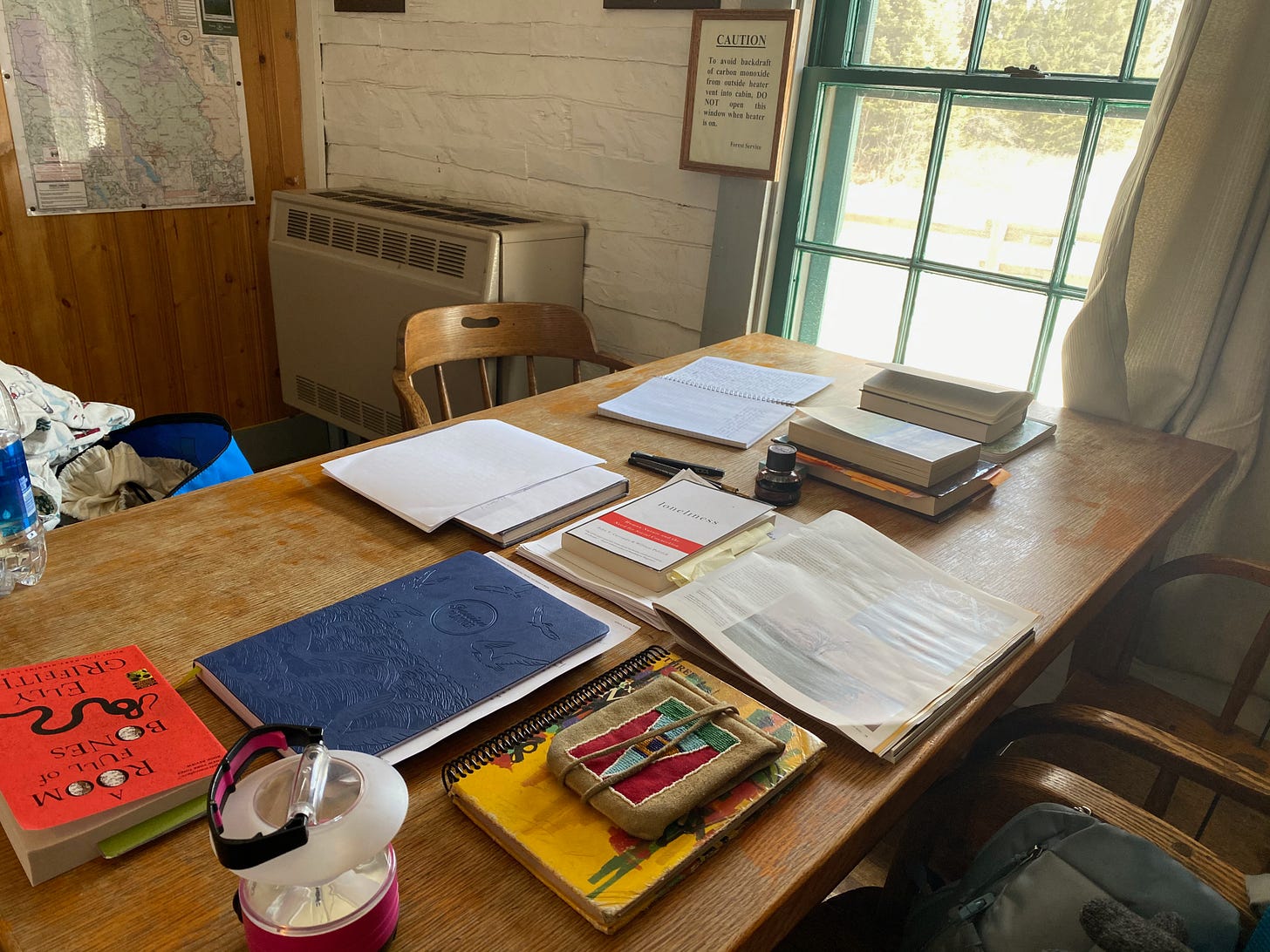

A few weeks later, I packed the piles and piles of research papers and articles waiting to be organized, a few books, food, coffee, sleeping bag, and went to a Forest Service cabin. I went again last month and have already reserved next fall’s stay. It’s getting a little easier on everyone. Kind of. A little.

Which is a relief because I desperately need this time. You’d think with my kids in school there’d be enough hours in the day to work, but between everyone’s appointments and errands and other commitments, school holidays, sick days, volunteer work that I try really hard to constrain, giving occasional walking-related presentations, and a variety of personal obligations, there is rarely a week where I can look forward to a full day’s work. A full day being defined as completely uninterrupted hours from 9 to 3.

When I’m away, by myself and offline, all that time is inverted. Open, ample, unspoken for. It’s luxurious. I get up at five or six and make coffee. Depending on the time of year, the first or second cup comes down to the river with me while I watch the sunrise. I stay there as long as I feel like, listening to whatever the river has to say and watching the peaks brighten in the sunlight. Then I walk back to the cabin and get some homemade granola, yogurt, and a couple of the peaches I skinned and froze last summer out of the cooler. Eat in no hurry, brush my teeth in no hurry, make some mint tea with the leaves I dried last fall in no hurry, and sit down to read and write. In no hurry. Through every moment the silence feels saturating, the relief of it tangible.

The first full day this last trip, after visiting the ice-slushed river for sunrise and then eating breakfast, I wrote for what felt like hours, read a chapter of a book for research, felt sleepy, took a short nap, made tea, made revisions on a printed draft of an essay; realized it was sunny and maybe warmer out, so took some personal letters out to the porch and wrote to people with more tea and a bare aspen tree and the sunshine for company (if you got a letter from me recently, I meant but forgot to tell you where I was writing from), read another chapter and thought surely it’s nearing late afternoon, I’ve gotten so much done. It wasn’t even eleven in the morning.

Not having to parent and run a household isn’t the only factor here. Being offline and away from phone service matters a lot. I once said to one of my mentors—who doesn’t have a cell phone or even a car—that being online felt like spending the day with a baby or toddler, which an acquaintance once wonderfully characterized as, “It really only does take half your time, but the problem is it takes 30 seconds out of every minute.”

Even if I’m not looking at the internet, even if I have Wi-Fi turned off, it feels similar. Just knowing it’s there is a constant draw on attention that drains away energy and focus, but also intrudes on attentiveness to the world. As I’ve said before, I really do enjoy the dialogues we have here, the shared ideas and comments. But I can’t do the kind of writing I do without making time for immersive attention in the world.

Letting the places I love pull me into themselves—the rivers, the starry nights, the moonrise over Glacier, the birdsong in a campground on early summer mornings, the snap of cold on a winter walk—and to not have to talk for days, even online, lets me be as much my full, authentic writer-self as possible. As a human being, that’s probably as good as I get.

Not everybody has these opportunities, or whatever their equivalent might be. When I first started my walking book, I spent a lot of time thinking about what mattered to me about it. I was tired to death of walking stories about philosophers and poets, the Wordsworth siblings and Henry David Thoreau. I wanted to write about walking that meant something to everyday people, which meant never losing sight of the question of barriers. If I believe that walking is a human right and fundamental to our evolution and health and well-being, what does that mean for places without sidewalks, for disability access and universal design, for all the ways in which walking is unsafe or inaccessible for far too many people? The question I pinned above my desk and carried with me was Who has the right to walk and where?

The kind of time and silence I treasure—alone, offline—to work or to think or to just be, the liquid feel of it, the expansiveness and luxury, feels similar. I know this time makes me feel whole, and my writing equally so. I think it—or whatever else helps people feel that kind of expansiveness, which might be something entirely different for you—can do the same for many of us. But who has access to it? Who gets to spend hours wandering in the woods, or days offline sitting by a river and reading books? I do, at least sometimes. Do you? Are there places to go and can you get to them? What about friends and family members and all the other people you know or don’t know? What are the barriers and in how many different ways do they manifest?

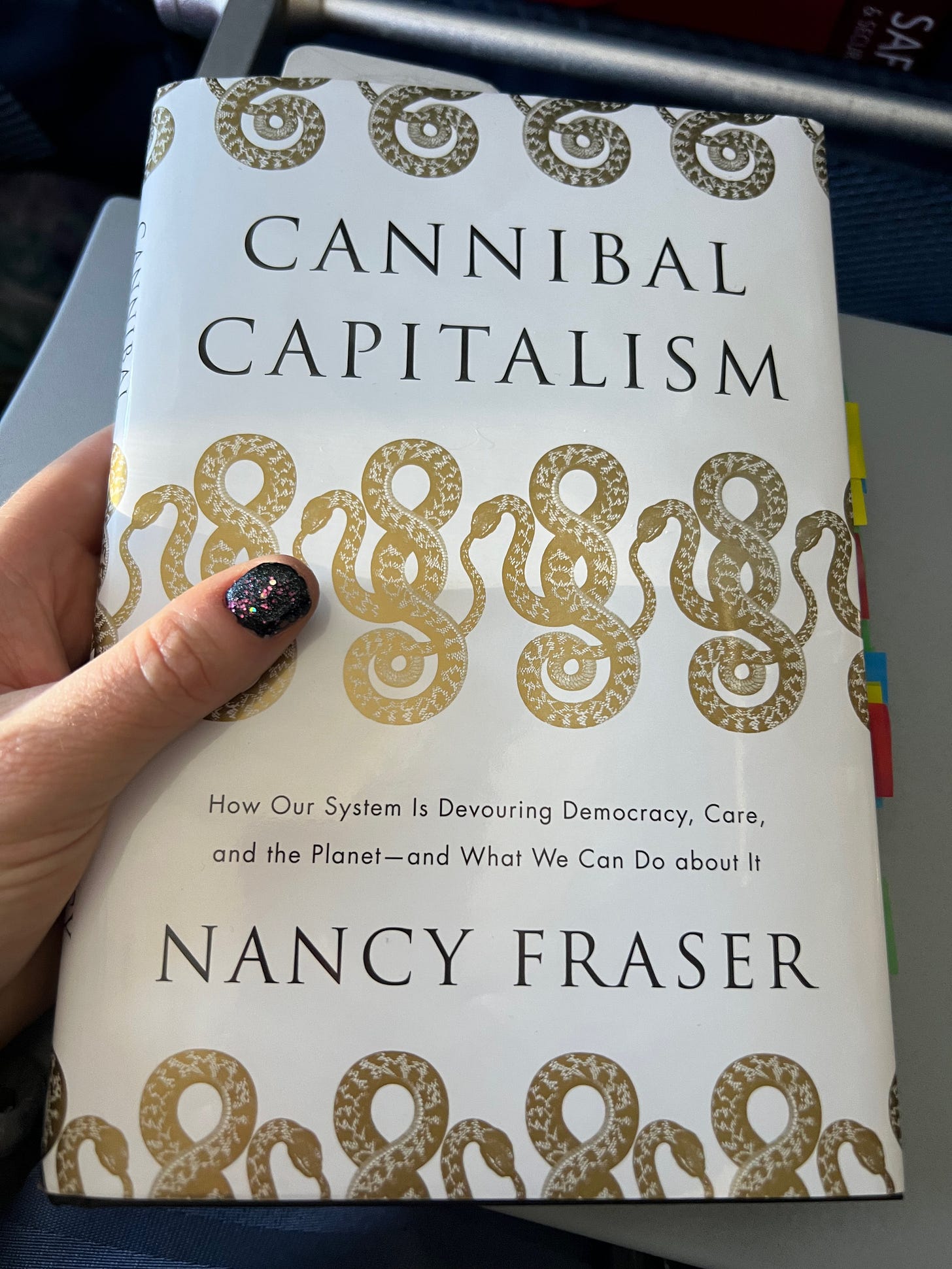

Thanks to subscriber Stefanie’s recommendation, I recently finished reading Nancy Fraser’s Cannibal Capitalism. I had trouble at first wrapping my head around the differentiation she makes between exploitation and expropriation, but the idea finally clicked, along with Fraser’s repeated point that capitalism will never stop devouring the world, even including the systems it needs for its own survival (like stable governments that enforce contracts and property rights). And including all of us—our work and our health and our relationships and our time.

The “What We Can Do about It” line in the subtitle is something I’d bet money Fraser’s publisher made her put in. “People need some hope” is something authors of books like these are often told, but Fraser’s only answer to “what we can do about it” is to completely uproot cannibal capitalism from our lives—from everyone’s lives.

The barriers of dictated time and schedules, and the single-family structures (absurdly patriarchal, still) and decades-long loss of wages that together create such immense pressures on caregivers, as well as everyone else, are some of the reasons why everyone can’t all go sit by rivers or get offline or hang out at a beach or go for a walk with a friend or take more naps or spend more time with your kids or whatever it is that feels most fulfilling to you. Underpinning all of that are the demands of capital itself.

I like working. I could spend pretty much all day every day at one of those cabins, reading and writing and wandering and listening to the river and the silence and interacting with almost no people and writing some more. I love it, actually. I feel restored and fulfilled and rested afterward.

I like other kinds of work, too, like chopping wood and digging in the garden and pulling knapweed and spending whole days hunting in the freezing rain, or hiking miles to spend a couple hours picking berries and then processing whatever I’ve brought home or gathered from the garden, thinking about what’s needed to get my family through the winter and early spring.

I do those things because I enjoy them and can make the time for them, but the reality is that as long as a few people at the top of the capital pyramid keep sucking up the richness of the world, including human labor and time and ingenuity as well as land and what are called “resources,” none of those activities will ever amount to much more than hobbies, even for me. Writing aside, I’d rather exclusively feed my family by spending time getting to know the lands we live among than by sitting in front of Google Docs and Word and Adobe for a copy editing job, even though I like copy editing, but the hourly tradeoff doesn’t add up to enough. My spouse would like more time to build bicycles and go hiking with friends and do things with the kids during the day, but his job is unlikely to ever release its need for people to be online and looking productive the bulk of the daytime hours.

That doesn’t mean it’s hopeless to do these things, or not worth it. In fact, I think it makes them more essential. Anything we can each do to throw grit in the system’s gears, to undermine it and erode it and remind ourselves that the barriers are mostly imposed and that we all have a right to be full, living, thriving, loving and joyful beings—it’s more than worth it, for all our sakes.

My spouse and I have to work—in fields that respectively interest us, fortunately—to eat and feed our children, as well as pay the mortgage for the house and the land it sits on. I make a lot of choices to scale back commitments, but not everyone even has that option. In the first two years of my son’s life he was hospitalized twice for severe asthma. We didn’t know if he might have major health care needs forever (he’s fine now), and I know too many people with that kind of responsibility, for themselves or for someone else. You can’t easily walk away from the system we’re in when the lives of those you love are at stake.

Instead of prevalent narratives that focus on these barriers, we find ourselves with books and podcasts on productivity or self-help or life-hacking that pretend we can find all the time and freedom we need by changing ourselves.

I know these tips and hacks work for a lot of people, but thinking about how many weeks or hours I have left in a day or a life to be productive or be healthy or be creative has never gotten me anywhere. I could get squashed by someone driving one of those idiotically enormous pickup trucks with lifted tires and a completely unnecessary Iron Cross bumper guard tomorrow. And writers of productivity and life-hacking books rarely address the very real structural and systemic barriers that most people face to making any of those changes. It’s depressing to think about, like being instructed on eating fresh, whole foods when you live in a food desert. Given the realities of my own life, too little of it is applicable. I once spent a whole school year running out to start the car and scraping ice off of the windshield while simultaneously brushing my teeth, and it wasn’t because I’m disorganized. You can’t really life-hack your way out of that. Whenever I read about someone who says they have, I usually assume there’s someone else—or a lot of someones, capitalism’s entire expropriated world at a minimum—doing some pretty heavy lifting behind them.

Escaping somewhere offline, by myself, makes it easier to see this disconnect. When I came back from my three nights alone and offline last fall, my sisters commented on my abnormal level of energy and happiness. I get to work. I get to sleep. I get to walk and think—and not think!—and sometimes just lie there on the bed of my truck staring up at an aspen tree rustling in the wind. I almost never have to talk to or listen to any people. In front of me are silence and time, silence and time. What if we all had something like that?

When I finished writing letters that one sunny day last month and started to feel cold and hungry, I visited the partly frozen creek for a little bit and then went back inside to heat up some pot roast. I read while eating. Made more tea. Took another nap and it wasn’t even 2 in the afternoon. Read some more. Wrote some more. Felt like I was wallowing in time. Like it and the quietness were alive. Like they were animate and present with me in a way I couldn’t describe.

Before sunset, I walked back down to the river in a cold wind that had sharpened over the last few hours. I stood there on the banks in knee-deep snow, my hands numb in my mittens, watching the alpenglow brighten and then fade on the mountains. Then I went back to the cabin in fast-growing dark, aiming for the little window shining with candle-like warmth from the single propane light. I put my feet on the heater and worked on an embroidery thing I was making for a friend while watching out the window for the full moon to rise.

I stitched away for an hour, lost in very few thoughts and only minor irritation at the stitches that refused to do what I wanted and had to be taken out and redone. And then glanced up to see one of the peaks bright in the darkness, light from an unseen source making all its snowy sides and ridges glow. I went out to the porch and watched for what felt like ages for the first strip of actual Moon to appear behind the mountains, arriving behind her light, and then for the minutes it took her to fully emerge above the mountains. Feeling awed and chilled and thrillingly reminded that what I was seeing was the result of reflected sunlight, and the planet we share life with spinning through space. I love that feeling so much, the slow sunrises and sunsets, how perceived movement of the stars brings to life the planet’s motion and gifts.

It was a day that lasted only about fourteen hours, but also forever. Containing more time, more living, than I feel almost anywhere else.

I went to sleep, moonlight streaming through the window, and woke up after midnight for a while. I went outside again into the animate silence, and there she was, high overhead, reflecting off beads of ice on a bare aspen tree. It felt like we had all the time in the world together. Like everything was going to be okay, even when it wasn’t.

Yes.

This was one of my favorite things to read in a long time. Thanks. I've got a similar kind of trip I've promised myself and it's now more motivating than ever.

So much of this essay resonates with me that I hardly know where to begin. Or shall I simply take a nap?

I was reminded of the last full solar eclipse visible in North America, It was in August of 2017. I had pitched a small tent in the yard of some friends who live in a very small mountain community within driving distance of my predetermined destination. I arose well before dawn and drove in darkness to an isolated area in the backcountry where there wasn't another soul for miles. The spot was in an area called "Cougar Flats," right next to "Bear Creek." So there was that.

After napping in the truck for a short while to make up for a poor nights sleep, I set up my camera on a tripod so that I could take pictures of exactly the same scene at regular intervals throughout the event. At those same intervals I recorded in a small notebook any changes in light, temperature, direction and speed of wind (approximate), and occasionally what I was feeling at that moment.

When totality finally came it was probably (except for watching the home birth of my youngest daughter) the most profound moment of my life--all alone, in the backcountry, with no phone or internet, and an uncanny feeling of oneness with the infinite. Having planned ahead, as the sky began to dawn for a second time that morning, I set the timer on my camera, stood in the frame next to the creek, and toasted the universe with a glass of Jameson Irish Whiskey. It was, after all, the least I could do to demonstrate my gratitude for the celestial show.

My solar eclipse experience was only for a day, and not two or three, and I got absolutely no work done, but it was nonetheless transformative. I crave times of quiet and solitude.

I'm going to read your essay again. Once was not enough.