When I was little, maybe eight or nine years old, I used to clean house for an older woman, Cora, who lived across the street from us. Mostly dusting and floors, for which she paid me 25 cents an hour. I did it for a couple of other families in Belgrade, too. Cleaning houses was my first job. And while we were pretty poor, I don’t want to mislead anyone into thinking that my family needed to supplement our food stamps with that money. My quarters mostly went to buy Jolly Ranchers down at the Kwik Way.

I loved Cora. She was kind to me and chatted calmly while I wiped down her surfaces and knickknacks, and she never balked at handing over the quarter or two. My mother later told me some stories about her, like how she and another friend had once climbed down Yellowstone’s version of the Grand Canyon when they were young women, assisted only by their hat pins.

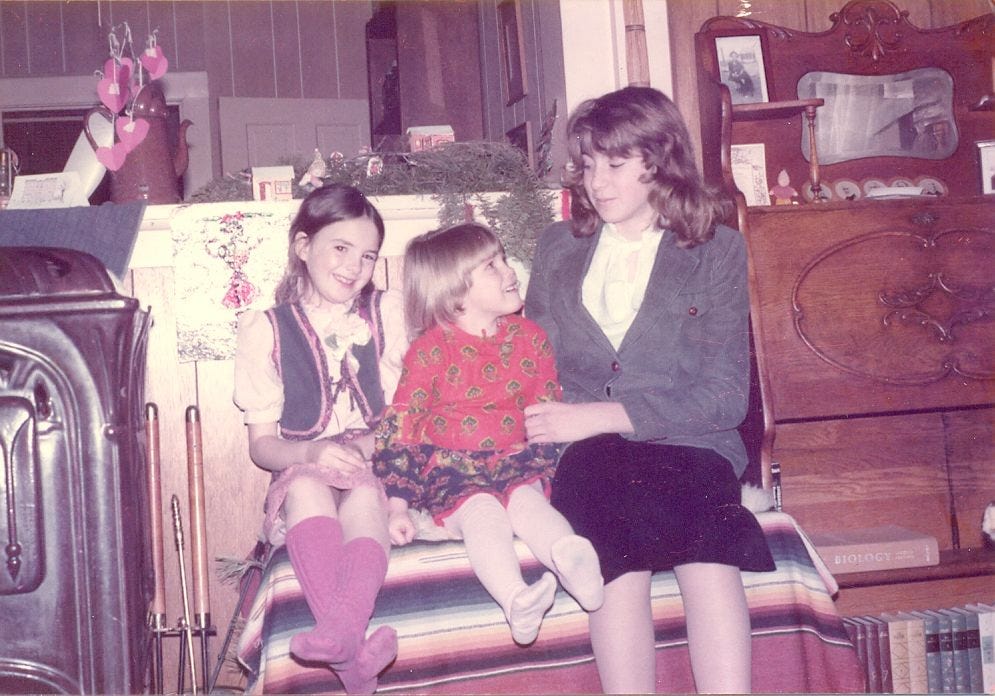

When Cora had to go into a nursing home in Bozeman, nine miles away, my parents took me to visit. I brought her one of the art projects I’d done in school, where we’d been using plastic wrap and aluminum foil to paint shiny snow and Christmas scenes. It was hard seeing her like that, laid up in bed in a bare room outside of her home, which had always felt comfortable and welcoming to me. It was harder when she died a short time later, on Christmas Eve. My parents told me after we got out of church that night, and I resisted having a photo taken with my sisters because I’d been crying.

Losing Cora that night is one of the minor reasons Christmas is difficult for me. She’s lingered in my head all these years. The grief I felt then, and later at her memorial service, are still tangible nearly four decades later, along with a growing wish that I’d known her when I was older, could have asked her about her life. That she lingered as more than a shred of memory for me, when her life was likely so very full.

Why do some people pull us into their lives, their influence remaining long after we’ve lost touch or they’ve passed away? There is no reason that Cora should have had such an effect on me, that I should have loved her so much and taken her death so hard, nor any good reason why her story has somehow become intermingled with mine. No reason that I can pinpoint, that is. I’ve searched for the bare facts of her life here and there, poking around in Newspapers.com archives, looking for old historical society records, and found nothing but a confirmation of her existence. But her effect on me is very real. I almost named my daughter after her, this woman who, objectively speaking, I barely knew.

Maybe some of the deepest impacts on us come from the people who slip out of this life without leaving many noticeable marks behind.

My older sister, who has five years on me, says that what she remembers being told is that Cora climbed alone out of the Yellowstone canyon using a hat pin, that one of her friends had fallen and Cora did what she needed to do to get help.

This is a lesson I’ve taken from most of the women in my life. From both my grandmothers in particular—my maternal grandmother, who believed in women’s education and independence and who lived a life of professional and voluntary service to others; and my paternal one, an engineer who raised children under Stalin and as a refugee during the Siege of Leningrad and whose ability to cope with impossible times I wish I’d had more time to learn from. They did what they needed to do, whether to survive or to help others do so.

At this time of year, because the memory of Cora is so sharp and I dislike Christmas for so many other reasons, I spend a little time lingering on my few memories of her, and of other women I’ve met in passing—in situations fleeting and far-flung—many of whose whose faces and names I’d never recognize again but whose stories have woven themselves somewhere internally.

Almost every Christmas ritual and tradition is, for me, something of going through the motions and trying not to ruin it for everyone else. With one exception: the moment when we walk down to the Luminaria and help line the river path and footbridge with candles in memory of those who are gone.

I have several lights to ignite, losses I won’t speak of. But Cora is among them, even though I only knew her for a short time.

Somehow, she’s still here, with the snow and the forests and the mountains I love so much, helping me get through.

Beautifully written, Antonia. I've been sitting here reflecting on my dad, a person who, though he was always there in my life (and continues to be now that he has passed on), remains an utter mystery to me. The reflections are amplified as I am editing the chapter in my book that tells the story of his passing, one my editor said was "one of the most lifeless," and I really don't know what to do with it. As written, I don't think I could get through it in front of an audience without breaking apart so who knows what it is missing. We do indeed all have these people in our lives and it is complicated. I hope I can figure out a way to get it on the page.

I am convinced that the only measure of immortality we can be sure of rests within those words of kindness and affection spoken about us long after we've left this world. And while it is up to each of us to plant the seeds of those words while we walk out this life, there are times when we sow unwittingly simply by being authentic and present in those fleeting moments of joy and connection with another human being. It's a little bit like magic.

You have done your beloved Cora a great service. Thank you for sharing.