Writing is a commons of ideas

I finished my master’s degree in creative writing a couple of decades ago, when I was in my late twenties. With a few exceptions it was an off-putting experience: the program felt designed to promote competitive jealousy and a slash-and-burn attitude toward others’ work. I’m not sure why I stuck with it except that it was a ten-minute walk from my Boston apartment and at that age I still believed it was a necessary step toward becoming a writer (and that “becoming a writer” was itself necessary, rather than just writing). I’m still friends with two of the people I met there, so it wasn’t a total loss.

Everything I learned about writing came after that. I eventually met good editors at various publications who taught me how to pare down my wordiness (not a lesson that seems to have stuck) and to really think about what I was saying. To question myself and the conclusions I came to, to broaden my perspectives.

Good writers might be rare, but good editors are far rarer. Those editors taught me to write.

More importantly, they taught me that writing a narrative with some meaning for readers is nearly always a collaborative process. This was not something that my master’s program ever highlighted, and not something that aspiring writers usually get advice about. It’s always “Get an agent,” “Get a book contract,” “Get your pitches accepted,” not “What allows me to do the best possible work?”

I can’t think of anything I’ve published, anything I think well of at least, that didn’t lean heavily on an editor’s input, and often also on that of a few particular colleagues whose judgment I trust. Feedback isn’t always easy to receive—writing is a weirdly personal thing, even if the subject matter itself isn’t all that personal—but it made all the difference for me.

Having my own newsletter means I can follow where curiosity leads and explore ideas that aren’t trendy enough for bigger publications, but I do miss having editorial feedback from people who know what they’re doing. Enough so that, as was the case with this essay, I often send On the Commons pieces to my older sister for feedback and corrections before I post them.

There is a group of people involved in writing who came up even less often than editors did in my MFA, if they came up at all: readers.

The interaction between readers and writers is very different in the full-on internet age of today from what it was when I finished my degree in 2003, when print still dominated and readers didn’t have such easy access to writers. Even once writing started going online, for many years the hard rule was, “Don’t read the comments.” Because they were junk or abusive or both. (They really were.)

Things have changed. I’m not exactly sure when. I remember publishing my first essay for Aeon in 2015, and how thoughtful and well-moderated the comments were, and how I was surprised to enjoy the dialogue they fostered. That essay had tens of thousands of readers and hundreds of comments. Not one of them was a waste of my time to read, and in fact several led to further research that informed my first published book.

Something shifts when readers opt into someone’s writing, and it’s not just the tone or content of the comments. It’s the way readers’ ideas and enthusiasm and questions become, for me, part of the thinking and writing process itself.

What shows up here comes from me, the result of whatever happens in the strange internal process called creativity. But the content isn’t purely individual. It’s “my” work, but also “this” work, something that readers have a stake in. Or a voice. Or something I can’t find the words for, something collaborative but not collective, or maybe vice versa.

Many of you send me emails with thoughts on something I’ve written, or suggestions for videos or books or podcasts, or personal stories of your own. Some of you post comments, or simply open and read the posts enough to remind me that people are giving their attention to whatever happens here.

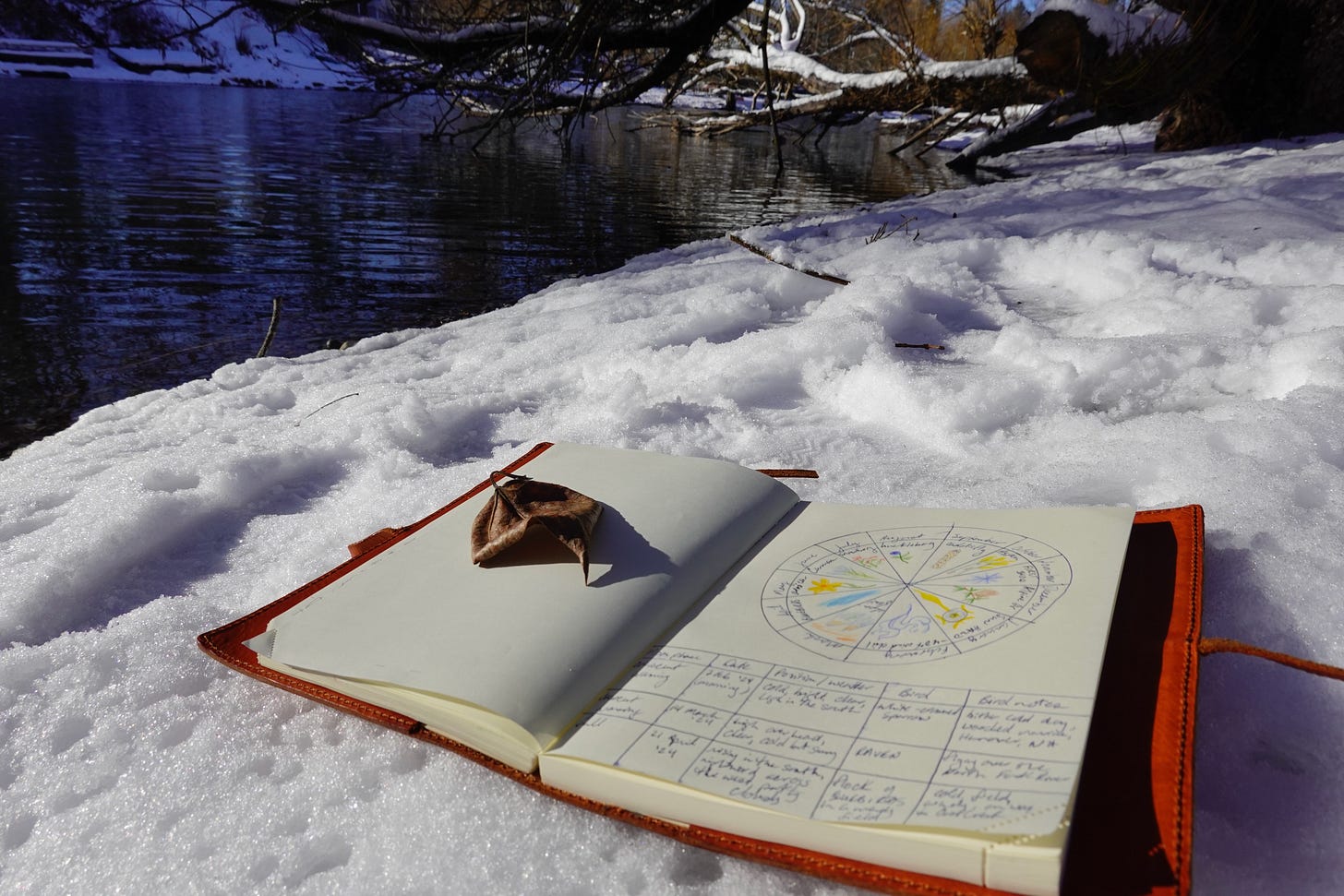

This writing comes from me—it is my mind, in a way. But that mind isn’t working in a silent bubble, absorbing books and articles and contemplative walks and conversations and churning out finished ideas. I think about you as I write. My first drafts, almost always written longhand in a notebook, are for me alone, but they can’t help but be informed by anyone who’s been reading and responding to what’s come before. The revision process also happens silently in my head, but it’s still a conversation with this group of readers and the world in general.

Where does this put ownership of the writing itself? And what changed once I started asking for people to pay for this work, even though there is no paywall? Who owns it?

Legally, I do—that’s what Substack and copyright laws say and let me tell you there’s a rich and tangled history behind creative ownership and copyright law—but isn’t it all of us? Isn’t this an ideas commons, too?

I can’t even claim full ownership of this essay idea. It was Mike Sowden of Everything Is Amazing who presented the idea of “narrative ownership” to me.

When I switched to the paid version of Substack, I decided to make these essays free and shorter pieces paid—this was for a brief period before I removed the paywall entirely—because the “some stuff to read/watch/listen to” lists I used to include represented about a quarter to a third of what I read/watched/listened to and took me a significant amount of time to compile.

Obviously, all the writing I do here is also work, but those lists were a particular type of work that felt more like easily identifiable labor. I offered the option of a paid-subscription-for-free-on-request because I didn’t want anyone to be shut out for lack of funds, but as time went on I realized that it was also partly because I wanted people to have the option of opting into something. I’ve personally unsubscribed from a lot of otherwise good writing (mostly on Medium) because I felt flooded with content I could never keep up with. I don’t want to do that to people.

Artists of all kinds struggle with being paid for our work. I don’t think it’s a struggle that we’ll ever resolve, even within ourselves, but it’s always worthwhile acknowledging that it’s there. And that, without art being paid for, generally the only people who can afford to do it are the already well-off. “You’re commodifying art” vs. “Then only rich people get to write” was an argument we had repeatedly in my MFA program.

Capitalism isn’t dead yet, and until it is we’re kind of stuck with the trade-off.

When I described to someone last spring what I was going to do with my book No Trespassing, publish it here as I slowly write it—I didn’t realize quite how slowly—he asked me what would happen if a publisher later approached me about publishing it in edited book form. I told him I’d thought about that a lot, especially after analyzing my own feelings when a couple of Substack writers I subscribed to moved to big-name publications. I didn’t begrudge them that—a steady paycheck is nice!—but there was a sense of loss after their announcements. A sense of, “Hey, you invited people to support your work; I was happy to help you build that and a lot of other people felt the same.” It felt weird, like some sort of rejection, especially as I didn’t want to follow them to the publications they landed at.

It’s an interesting feeling, not one I’m proud of or even fully understand, but one that did make me think carefully about what I was doing here.

It feels akin to starting a relationship, I think, reaching out slow, tenuous tendrils that you can’t just retract on a whim if you change your mind, not without injuring both others and yourself. Whether you’re sharing writing or relationship, each tendril is made of trust, and you can’t impulsively walk away from those things without damaging that trust.

I told this person that I wouldn’t be averse to the idea, if a publisher were interested, but there’d have to be something in it for all the people who’d already been supporting this work, financially or otherwise. That I wouldn’t want to give a sense of “Thanks for your support, on to bigger and better things now.” What that would look like I don’t know and it’s purely theoretical at this point (and will probably remain so). Free copies? Acknowledgments? A promise to keep doing this work, here, together?

It’s not a simple question, but to rebuild the commons—all the commons—it and others like it have to be answered, in some form, eventually.

No matter what, though, I can’t think of this Substack as something I myself own, that I myself am creating and can be possessive of any more than it was solely me who created any other piece of published writing with my name on it.

Copyright law tells me one thing, but what I’ve learned from working with good editors over the years; and how I feel about ownership; and what I envision as a better, more reciprocal, way of doing this collective thing called life could be, is quite another.

I don’t plan on doing guest posts here, or interviews—I can barely keep up with my life and work as it is, and really isn’t everyone already overwhelmed with material to read and listen to anyway?—but I do think of this entire project as a kind of commons.

I might be sitting here alone at a desk shaping narrative as best I can, but copyright law aside, nobody really owns these stories, much less the ideas that seed them.

What that means I’m not sure. I do know that, if you’re here with me, then I am equally here. With you.

As always, I read your words and they are both incredibly calming and reassuring, like listening to someone explain something I've felt for years but never quite put into words, and also, EXTREMELY ENERGISING because they make me want to leap up and write a 20,000 word response. And I think that's part of the joy of this writing-commons approach. In Seth Godin's phrasing, we infect each other with the idea virus (it's funny how that analogy is no longer as appealing as it once was), or perhaps we're like musicians jamming off each other, finding deeper layers of the melody.

Or maybe: it's just how great writing happens, Mike. Stop making everything a metaphor.

I feel the same way as you do about writing in my Substack - with the knowledge I'm relying completely on the original scientific research of others, so even if I tried to claim "ownership" in some way, I really couldn't. (Which is why when something of mine suddenly reaches a wider audience and I get feedback like "this is amazing, thanks, random English guy" I feel like saying "thank you, I'll pass it on to the people doing the actual work!!!" and then present them with a hundred-entry bibliography).

I also feel like you do about traditional publishing. I'd love to have a publishing deal! But I wouldn't want to adapt something that deserves to exist elsewhere, because that's where it can be weird and risky and commons-y enough to flourish. It feels like an unspoken loyalty to what the work deserves, and from my (totally inexperienced) perspective, tradpub feels like a very different beast: much more risk-averse, much more grounded in marketing systems that have been around for decades and that are looking increasingly dusty and over-safe at least to my eyes, and operating on a work-cycle lasting *years*, which horrifies me in the same way when I was a freelancer I could never understand why the biggest publications were the ones that took the longest to pay me. (With a *check*. WTF.)

>>"I told this person that I wouldn’t be averse to the idea, if a publisher were interested, but there’d have to be something in it for all the people who’d already been supporting this work, financially or otherwise."

This really got to me. It's how I feel too, so much at this point. The kind of gratitude for my readers that makes me blink a bit faster. And - I never want the folk who have invested their time and money in me to feel like it was a bad bet. Whatever the finish-line is of the projects I've invited them into, I want to meet them there. I want us all to cross it together. So - YES. This. Thank you so much for putting it into words, because now I can see how important it is to me on so many levels.

I'm stopping this comment now because I'll write another 19,300 words, just you watch me. But I may come back.

Bravo. I love the way you're approaching all this, Antonia.

(And thank you for the kind shout-out! But I don't think that's my idea at all, I probably stole it! See: "even if I tried to claim "ownership" in some way, I really couldn't". 😄)

I have been contemplating this same idea, thank you for voicing so many of my thoughts and feelings!

I feel conflicted about the idea of entering my work into the commons. On the one hand, I love how my work is influenced by those who read it, and how that shapes my future work. Whenever I write something it’s not because I have something figured out, it’s because I have an idea. And after I publish that idea it enters into debate where commenters can think it through and provide further reading material as we attempt to answer unanswerable questions. That informs my work, guides it. I have completely changed my mind from one post to another as we shape one another’s ideas. It’s like a moving thought. It’s, like you said, part of the commons. This “figuring it out together” quality feels like a modern literary salon and I’m obsessed with it.

On the other hand, that constant feedback can be too much for me. Even if it’s good feedback. Sometimes I look back on the three years when all I was doing was writing my novel in solitude, with no social media or feedback on me or my work whatsoever, as one of the most beautiful times in my life. It was purely my thought. My ideas. If they were right or wrong it didn’t matter. They weren’t part of the commons. They were just mine. It was hard to then expose it and get feedback on it because it was just purely me. And I didn’t want feedback on me.

Now, I try to do as you do, to feel that the reading and writing is mine, but that once it is published it becomes ours. But I can also hear a thousand voices and commenters in my head when I’m reading and writing, so even that isn’t purely mine anymore. I feel that my mind has become influenced by so many (often conflicting) online voices that it can be difficult to even have an idea at all (because in the eyes of the internet, the idea will always be wrong to someone....) In this way, my mind can feel a little hijacked by the public. Like I can’t even express myself without commentary on that expression. And that makes me afraid to express myself because of the commentary I know I will receive on that expression.

I’ve even found myself taking a break from reading on Threadable because it feels like even my time of quiet reading and contemplation can be commented on. And I needed the space to have original thought about my readings without worrying what someone else might think about them. I’m curious how you’ve thought about that?

Anyway, sorry for the long response. You just really struck something in me today. I’m still trying to find the balance between mine and ours in my art (and maybe that’s symbolic of the commons in general-what is mine and ours?) Thank you for providing this space to think it through. I really appreciate your work!