If you’re new here, welcome to On the Commons!

Here, we explore questions as varied (but related) as: What is the difference between attention that fractures us and attention that restores? What role have three 15th-century papal bulls served in the “claiming” of land worldwide by Christian peoples of European descent, and how have those claims evolved?

Reminder: If you pay for a full annual subscription, I will send you a copy of my first book, A Walking Life, as long as I have some left. If you already have an annual subscription and haven’t yet gotten an email from me with this offer, please tell me!

Also a reminder that all of these essays are cross-posted to my site on WordPress.

Audio version (correction: the study on intergenerational wealth mentioned covered 600 years, not 400):

After recording the audio version of my most recent piece here, on the 1805 property law case Pierson v. Post, I spent a very frustrating hour trying to get my voice recorder to talk to my laptop. Or my laptop to listen, I don’t know which. I kept getting a message that the device wasn’t “recognized” and given the options to ignore, eject, or initialize.

I unplugged and replugged everything several times, turned them off and turned them back on, again several times, every order iteration I could think of. The Sony voice recorder’s troubleshooting page was unhelpful.

Finally, I went for “initialize,” which I’d avoided because I’m a very non-tech-minded person and things like that scare me, hinting as they do at “going to erase everything.”

A screen popped up with a lot of options I couldn’t decipher, but I clicked on the most promising sounding ones, and magic, the laptop suddenly recognized the voice recorder.

I was reminded of when I have to confess my mild face blindness, which frequently results in my being unable to recognize people I’ve known for years.

I told

after this ordeal that I was on the verge of giving up, deleting everything, and sending him bad photos of birds instead, plus one that had kindly run the starling photo through Photoshop for me, making it less-bad.

The next day my phone, a non-smartphone with no apps or internet capabilities, called three people while I was clattering around the kitchen making dinner and listening to my son tell me about his recent school trip to Washington, D.C.

My phone, bless its sane heart, calls people all the time without me asking it to. It also hangs up on my older sister all the time when I’m talking with her. It drives me nuts. I’m constantly tempted to give up on this whole living-without-a-smartphone thing just for that reason.

I got this phone, a Light Phone, back in February, and spent a few months carefully transitioning to ditching my iPhone, which I did in June.

Even with those months of careful preparation, I didn’t realize how dependent I’d become on things like the mapping navigation feature until trying to drive around Portland, Oregon, with my son in August. I’m 48 years old. I know how to read a map. I love maps! I navigated unfamiliar cities without a smartphone until . . . 2015? 2016? How did I lose that capability so quickly?

And how did owning a smartphone become a near-requirement for modern life in that brief timeframe? In August, I took my younger kid to an event that required tickets be presented on a smartphone. Agents checking you in at an airport fumble when I present them with a paper ticket. The yoga class I take my younger kid to at the community gym requires people to register ahead of time, which has to be done via their app, so I end up having to call each day we go because I don’t have the app.

The county commissioners where I live tried to require smartphones to use the anemic, almost nonexistent public bus system, a blatant effort on their part to make the lives of unhoused people even more difficult. I saw a raffle giveaway at a public event recently that required people to scan a QR code to enter.

The demands that technologies make of us can be overwhelming, even if you’re someone who benefits enough from those technologies not to be particularly aware of said demands. It’s too-infrequently asked how we’re expected to bend and shape our lives—all life, really—to the needs of technology, rather than the other way around. Being sold stories of how much any particular technology gives us doesn’t change its demands, or what it takes from our lives.

I’ve written before about the parallels between digital technology and the invasion of automobiles and the roads they require, including in A Walking Life, in which I wrote that

“The future before us requires us to face the realities of our world full-on, and to figure out both what we want from our most cutting-edge inventions, and how they can serve us better, how we can reclaim our physical world, our physical selves, and the time and attention to appreciate both.”

Some time ago, a subscriber had recommended a series of lectures to me from the 1980s, physicist Ursula Franklin on The Real World of Technology, and I now go back to those talks repeatedly.

Franklin starts out talking about pottery making in ancient China, and what kind of shift is demonstrated when vases stopped being individually crafted art, and became something produced en masse to strict standards of quality and conformity.

Technology, she said, is often introduced as a form of social control, but over time people begin to see it as normal, or even necessary. Like cars. Or the looms that the Luddites smashed—not because they feared technology but because they recognized its introduction as a way to increase profits for factory owners at the expense of their jobs, and at the expense of the product’s quality.

Property law is a technology. It has shifted over time to continually expand what rights people think should be granted with ownership, and what rights everyone else, non-owners, lose. The right to prevent “trespass” being one of the more recent and most egregious.

Franklin pointed to several legal technologies that restrict freedoms and imagination, like certain tax codes or contracts. And even in the 1980s she saw early computers’ potential for defining and limiting how and through what mediums people communicate with one another.

Even though I tell people how many things I miss about a smartphone and what a pain in the ass my sane phone is, I rarely meet someone who doesn’t express a longing for the freedom to make the switch; or, likewise, the freedom to give up social media platforms, both technologies often required for one’s job.

What cars and roads have taken from us, the damage they cause, is measurable. I covered plenty of it in my book, from the effects on lungs and brains of car exhausts’ pollution, to the higher rates of social capital in walkable communities.

of recently wrote about the pollution from cars’ tires, a reality that haunts me, to the point that I gave public comment at a city council meeting several months ago—related to a missing section of our bike and pedestrian trail—about those microplastics shedding into the river.The effects of social media and smartphones are more difficult to pin down and are almost always subjective. I have talked before about my own social media addiction, something that many researchers still insist isn’t a real thing. Likewise with screen addiction, which I’ve seen in some kids firsthand.

The invasion and theft of attention is unlikely to have excellent science behind it anytime soon. There are too many conflicting and confounding factors. But when I spent some time recently wondering why I started developing an aversion to Substack, I realized it was because interacting with it, or even thinking about interacting with it, was making me feel exactly like I used to when I was on Facebook. I deleted my FB account completely in 2017 after years of repeated deactivations. My mindless scrolling took up hours, and even thinking about being on the platform wrecked my creativity.

This is a specific phenomenon that I find difficult to describe, and am curious if others have experienced it, too.

When I was on FB, someone created a group called Binders of Women Writers, which I was invited to join early on. It quickly became vast and generated many subgroups of genre, identity, region, etc. For a long time, for me, it was wonderful. I’m still friends with people I connected with there, especially in the science writing world, and suddenly had access to editors at bigger-name publications that previously had seemed out of reach.

But when the social expectations of those groups started to seep into my personal page, it became a problem for me. I didn’t always want to repost essays that old family friends might find offensive or hurtful. My personal relationships are very important to me. I’d joined FB in the early months of new motherhood to help alleviate the isolation of living in a rural area with a new baby, and found myself reconnected with many people I cared about and had lost touch with.

The scrolling—the way I do it, literally mindless—got to me, the way I lost time when I was meant to be working, and the blurring of my personal and professional lives became frustrating, while at the same time interacting with FB tended to dilute most of my creative ideas, to the point where many of them would fizzle away if I weren’t careful.

Being on Substack also reminds me of Instagram, which I left in 2020 after getting fed up with curating a “self” online in the midst of a months-long family crisis. The effort it takes to curate a “self” here, on Substack, often feels similar.

And it increasingly feels similar to Twitter’s expectation of constant, immediate opining on every issue of the day, large or small, which I am almost less interested in reading than I am in writing. One of the reasons I admire

’s newsletter so much is her ability to her use own life experiences and insights to provide broad and deep contextual thought for the problems and horrors our worlds face, like her recent essay about being put on trial for her novel The Bastard of Istanbul.This is not an “I’m leaving Substack” thought; it’s an “I’m trying to figure out how to do this in a way that feels better” thought. In the past few months, I’ve come back from offline time at forest service cabins or camping to find that the usual buildup of emails and messages feel like innumerable straws quickly draining my psyche.

It takes effort to keep one’s mind strong in the face of being urged to and rewarded for quick responses; I have wondered if Shafak’s dedicated longform fiction writing helps keep those muscles in shape. It’s hard to imagine a book like her most recent There Are Rivers in the Sky even being possible for an imagination pulled into constant online responses and reactions every day—or worse, bent into knee-jerk contrarianism so habitual it ends up being, as I read someone describe a self-anointed “thought leader” guru-type recently, in a situation where “Sometimes contrarianism can be such a strong trait in a person, it bends one into actual bullshit.”

To keep our attention intact and strengthened is a fight, just as hanging onto the freedom to walk and wander is a fight, and it’s not going to get any easier. I’ve been through this self-internet recalibration process many times over the last 20 or so years.

Most of those who create digital technologies, and benefit from them, have no interest in changing its design to truly benefit the rest of us, much less the rest of non-human life, the Center for Humane Technology being a necessary if imperfect outlier. And complaining about all of it online only fuels the machine. Attention is attention.

I recently read Clarissa Pinkola Estés’s book Women Who Run with the Wolves for the first time. Of the many lines and passages I marked in my copy was this one:

“We wish to make rage into a fire that cooks things rather than into a fire of conflagration.”

The problem with “burn it all down” (and I’m not saying I’m immune to this) when it comes to the systems we exist under is that those who will suffer most are those who already suffer most. Most of those who benefit from the systems, and cause the most damage, have ways of shielding themselves. One piece of research that has stuck with me in this work on private property and the commons is a study of intergenerational wealth in Florence, Italy, over 600 years, maintaining itself even through wars, revolutions, massacres, plagues, . . . burning it all down doesn’t get to the root of the problem.

What, instead, can people do to create a world worth being in, to transmute rage and grief and a fierce knowledge of injustice into something flourishing, something alive?

What gives you the skills and focus to cook without starting a grease fire in the kitchen? Do you know how to tend a wild burn so that it nurtures new growth, without fueling a conflagration that kills everything? Where I live, plants like huckleberry bushes, camas root, and lodgepole pine trees need fire to flourish, but if a wildfire burns too hot for too long, even they will not regenerate. The fire needs control, needs tending, needs the kind of kinship that comes from intergenerational knowledge—a better form of wealth.

I heard the term “pyroepistemology” for the first time in the last year or so, applying the concept of controlled fire to clearing ground for new and old ideas. Maybe it can be applied to our own sense of attention and belonging.

I recently stood under a mountain ash tree on a walk home and watched a flock of cedar waxwings nipping snow-dusted berries off and gulping them down. I had forgotten to bring my camera out and could only stand in the snow and watch, trying to fix those moments in my mind—the soft yellow-green of the birds’ chests, the dark red winter berries against my favorite color of indefinable blue-grey sky.

These moments keep alive in me my desire to build and care rather than destroy or complain. I’m trying to bring more of them back into my life. I recently started playing my harp again, and continued working on an interminable embroidery project thingy I’ve been making for a friend for close to two years.

I’m trying to find ways to get more familiar with my own rage and its sparks by spending time with myself and the real, glorious world that wants tending and care and its own nurturing fires.

And I’m trying to find better ways to be online, for myself, putting boundaries around the demands of time and attention, at least within what my work requires. It’s never going to be easy. There’s every incentive to stop trying, just like there is every incentive to give up on walkable communities and the removal of borders and barbed wire fences. Like everything else that makes us human, it’s worth doing anyway. Being better humans, more human, has to be part of being good ancestors and building a world worth being born into.

With that in mind, if you’ve made it this far, don’t share this essay. Or, do, but not yet. Do something to connect with yourself first. If you’re into breathwork, do one of those practices four times. Or stretch your arms overhead for 20 seconds. Go for a walk. Hug someone you like. Ruffle your dog’s ears. Write a letter with paper and pen. Do one of

’s 24 Days of Making, Doing, and Being. Rest your feet in running water. Cry for a loved one who’s gone. Cry for the world. Listen to the songs toward the end of this healing conversation about kinship and indigeneity across cultures and time with Dr. Lyla June Johnston and Angharad Wynne (singing starts around 1:03).What can you do, this moment, the second you get to the end of this essay, to feel alive? To feel as fully present in this-world as possible? Can you feel that shift in yourself, between how you feel when you’re binary in all senses of the word, and when you’re vibrant with awareness of how the air of your home smells?

Where are you? Who are you? What are the embers beneath your unique, individual fire? And what can you do for yourself, today, right now, to bring it all back home?

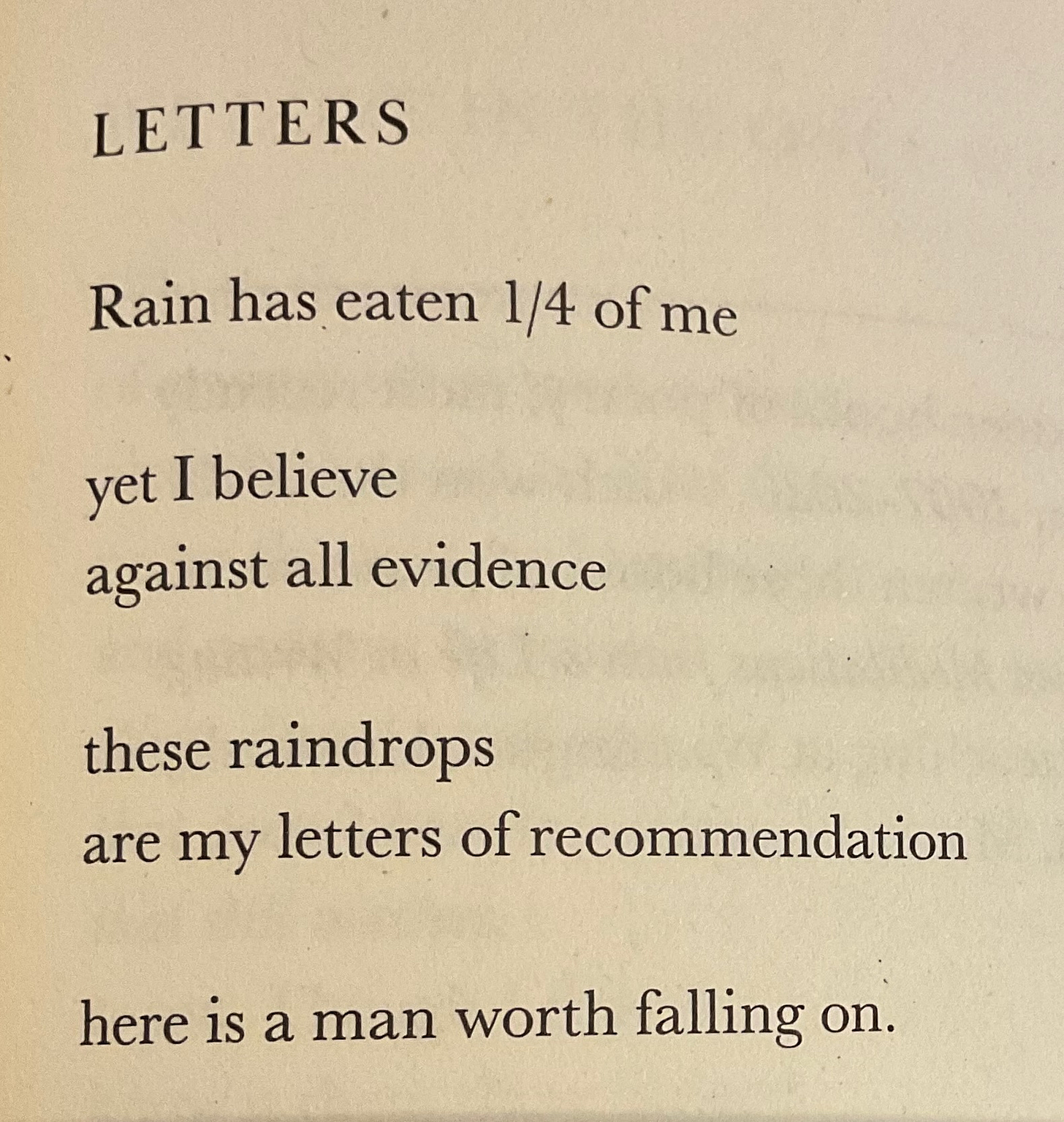

Ilya Kaminsky’s poem “Letters,” from the anthology You Are Here, edited by Ada Limón and sent to me by a wonderful friend.

Thank you, Nia, for another beautiful and thought-provoking post.

Technology is tough. We're in New Zealand for the month of December and we'd be lost without a smartphone. Our rental car assumes a smartphone with google maps to feed the navigation screen. The parking meter in front of our waterfront AirBnB assumes a smartphone, and so on.

There are other aspects of technology and capitalism that are hard to opt out of. To have a retirement income, for example, we must believe in infinite economic growth on a finite planet. The natural and spiritual worlds, of course, have none of these concerns.

I have come to realize that the key to survival for me is to accept that these are parallel worlds operating with different rules and to learn to move between them without losing my place in any.

Thanks for making me think!

I nearly quit Substack today myself. Freedom of speech in the US is for the independently wealthy, and I have nothing to say lately that can't be used against me.