If you’re new here, welcome to On the Commons! Here, we explore questions as varied (but related) as: What are the ongoing consequences of land enclosures in England from the 1400s onwards? How do each of us perceive ourselves as kin with the rest of the living world? What do true believers and echo chambers have to do with authoritarianism?

✔️ Join a community of over 5,700 On the Commons readers. Upgrade here.

Oglala Lakota Artspace, a mixed-use Native arts and cultural center on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, will receive 5% of On the Commons paid subscription revenue from now until the end of the year. (Accountability: this page shows receipt of revenue return from each quarter.)

Non-Substack writing! Elementals, a new anthology from the Center for Humans & Nature, is out now: “The Elementals series asks: What can the vital forces of Earth, Air, Water, and Fire teach us about being human in a more-than-human world?”

I have an essay titled “Trespassing” in Air, alongside stellar writers like Báyò Akómoláfé, Ross Gay, and Roy Scranton. Other volumes include writing from Robin Wall Kimmerer, Andreas Weber, Tyson Yunkaporta, Sophie Strand, Joy Harjo, and many more. As with their previous series Kinship, this anthology brings healing and guidance to a world sorely in need of both.

Audio version:

“But all worthy things that are in peril as the world now stands, those are my care.” —Gandalf the Grey, Lord of the Rings

There is an apple tree in the yard my home sits on, a tree that was here for decades before my family lived near it. Recently, I made an emergency call to a septic company because our tank wasn’t draining, and one of the guys who came by said his grandmother used to live here. I told him he can come and eat the apples any time he likes, and he gathered a couple for him and his coworker. Said he had no real good associations with his grandmother or that place, but that they’d always been good apples.

Usually, a friend picks all those apples for her annual cider-pressing, but this year they sat longer on the branch than I’d ever left them before, well past frost, and when my younger kid and I tried them, they were sweet and still a tiny bit tart, firm and full of juice. I’ve rarely tasted apples like these, only when we lived in upstate New York surrounded by orchards and I learned that apples could taste good, nothing like the Red Delicious and Golden Delicious that were the only grocery store offerings when I was growing up in Montana. Those were anything but delicious, not worth wasting our food stamps on, and I was nearly thirty years old before I tasted an apple I actually liked. Good fruit has always felt like a luxury to me.

Dried apples go a long way through winter and on long hikes and long drives alike. Last year a generous person—and subscriber here—let me and a friend pick from her trees, tiny Transparents that were a chore to peel, core, and dehydrate, but make the best dried apples I’ve ever had. Sweet, tart, a bite of late summer to keep us going even when spring feels long in coming.

I didn’t get to those this year, a year of upheaval and chronic overwhelm, but it inspired me to pick our own apples and dehydrate them for once. So my kitchen is soaked in the smell of warm apples, those slices in the humming dehydrator that I have to scooch back now and then so it doesn’t vibrate itself off the counter.

I like the way my kitchen smells in the fall, especially when I’m still processing fruit, shifting among boiling jam and plum fruit leather dehydrating and scalded peaches ready for their skins to slip off. This year, there was warm apple in the air, and sweetgrass from the very first cuts of the plants my neighbor gifted me. He and I talked while he showed me how to gather handfuls of grass that smells like . . . something warm. Like apples in the sun, actually, but with a hint of sage, too. Wild white sage, not the savory of cooking sage or the sharpness of thick, prickly big sagebrush.

There’s a whole book to be written about the scents of sages.

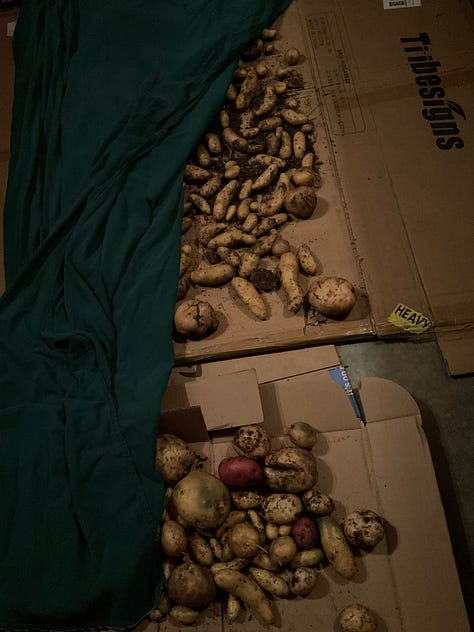

I scrambled around getting the last of the carrots and potatoes in, leaving several explosively large zucchini on the vine. My kid and nieces were still picking a few strawberries past frost—I have never grown strawberries like this, sweet and warm and productive all summer and into the fall. There was even enough to freeze, and I’m thinking of midwinter jam.

The raspberries took a couple years to establish themselves but are now taking over large sections of the garden, and the elderberry bushes have finally produced enough deep indigo clusters of pinhead-sized berries that some remained for people after the birds had their fill. My friend took half of what was left to experiment with the cider she ferments from her annual apple-pressing gathering. My brother-in-law took the other half to soak in vodka, and gathered buckets of buds from the hops I planted a few years ago. His garage smells of them, a snap of herb and earth that is somehow beer-ish while being nothing like beer.

And after two years of attempts, I’ve finally managed to nurture a tobacco seedling to life on the kitchen table—one of the varieties of Nicotiana rustica I got from Strictly Medicinals, but it’s been such a saga I’m not even sure which variety made it. I’m happy to see it bloom, even if I don’t get around to harvesting the leaves. Which I might not. I just started rewatching Star Trek: The Next Generation after delving into a handful of Planet of the Apes movies for the first time.

There are too many things I never get to. My brain is fried and my hands are always busy.

The fruit is now all bedded away for winter. It’s nearing time for stews and soups, for roast things and digging food out of the freezer, longing for fresh fruit as the months slip past. Wanting to hang onto the long, dark nights wrapped in stars and moonlight as long as I can while February days lengthen. I love winter. The cold. The snow. The dark. The hours I get to myself watching moonlight play with the clouds.

Wondering how many billions of humans have watched that same Moon wax and wane over tens of thousands of years as their worlds crumpled with darkness of the heart.

Twenty-five years ago, I worked as a church secretary in Vienna, Austria. The church was Anglican, attached to the British embassy, and was well-attended by Brits, Australians, and Canadians who worked at the embassies or for the UN. I worked at none of those places. I was by then living legally in Austria, having married a Brit since moving there (the UK hadn’t yet Brexited out of the European Union), but both my jobs, church secretary and the other one as a journalist for the English-language newspaper, were illegal. I’d fought through the Austrian Foreigners’ Police department to get a residency visa after getting married, and was taking intensive German classes every weekday. I was 22 years old and filled with wanderlust. I was also an atheist, but we barely made enough money for groceries and illegal or not, I needed a job. When the former church secretary left to attend seminary school, I took the position.

I spent long hours in a freezing cold vestry typing letters for the priest, a delightful man with fiercely progressive values who was relieved when I told him I preferred not to continue the previous secretary’s habit of praying together before our office hours.

One of the regular churchgoers, an Englishman and artist, had begun a project to design a plaque commemorating the actions of a long-dead priest, Reverend Hugh Grimes, who had quietly started converting Jews to Christianity in 1938, in hopes that the baptisms would allow them to leave the country.

The artist wanted to include on the plaque the priest’s verger, an Austrian known only as Mr. Richter, who had been instrumental in helping in the baptisms over the space of a few months. He was, I was told, later murdered in Auschwitz.

One afternoon, trying to find any record of Mr. Richter’s full name, we dug out several oversized original baptismal record books; they’d been sitting nonchalantly with the rest of the retired church records in the back of the cupboard used to store the priests’ vestments.

I boiled water in the electric kettle and made tea, which would go stone cold within minutes in the chilly vestry, and we began skimming through the 1938 entries.

Between each name and date of baptism was listed the individual’s profession: “Shopkeeper,” one of us would murmur to the other. “Butcher,” or “housewife,” said the other. “Seamstress,” the artist translated for me. As we read we began to slow, growing silent. I started looking at ages: most of the people were adults. Married couples, families, streaming through the same massive wooden doors that my husband and I now entered every Sunday, except these people were shedding their faith in the hope of saving their lives.

Approximately 1,800 people were baptized from May to September before the Church of England summoned Reverend Grimes back home. I tried to imagine the physical organization, the hurry, needed to baptize that many people in such a short time. On a single day 229 people were baptized, in a church that only seated 125.

It wasn’t until that afternoon that the reality of the Holocaust’s metastatic growth, the sense of fear in the erosion of what had recently been a normal life, crept up through my fingers and stored itself in my understanding. I could almost smell it from the pages—the urgency to get baptized quickly, one after another; the desperate, frightened people; Reverend Grimes and Mr. Richter acting quietly, as fast as possible, before the church shipped Grimes home.

The artist, the priest, and I were shaken, gripping our cups of cold tea. We knew what these silent names in the ledger couldn’t have at the time: for many, maybe most, of them, abandoning their faith wouldn’t save them. Long before Hitler came to power, purity-of-blood laws that declared Jews unequal simply by their descent had overcome communities and countries like raging tides for arguably nearly 2000 years. In 1938 Austria, it was only a matter of time before a person’s religious affiliation wouldn’t make a difference.

“If you’re going to fight, fight somebody who has power over your life, don’t fight fucking strangers on the internet. If you’re going to perform labor, let it be impactful.” Jessica Lanyadoo, Ghost of a Podcast

I wrote recently about the moral codes my Russian-Jewish grandparents lived by, even under Stalin’s Great Purge that killed at least hundreds of thousands in the Soviet Union, values that can withstand history’s wreckage. It’s the lessons left by them, and by people like Hugh Grimes and Mr. Richter, that I turn to in hard times. I don’t know how to explain horrific human-caused events at scale. I look back through the history of just the European continent, soaked in blood century after century, and do not know how to explain war after massacre after invasion after war at scale. Or the recent and ongoing actions of Israeli soldiers in Gaza. Or the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. Or the Ukrainian Holodomor, the man-made starvation of 1932-1933 that killed millions. Or the Rwandan genocide of 1994 that saw half a million to a million murdered, and was defined by the use of mass rape as a weapon. There are literally countless more of these throughout human history, including today, and tomorrow.

One person’s evil, one person’s pathology, I can get my head around, but en masse, it breaks any understanding of humanity. I don’t know how to comprehend any of these at scale, and am skeptical of the judgment of anyone who claims they can.

But the courage to act according to what is morally right, what is human and humane, when all the forces around you demand otherwise, that I can understand. It’s those people I look for, in good times and bad, because even the supposed best of times are not good for everyone.

I look for those who care, who give, who tend to the wounded in heart, mind, and body, who fight back in ways that slide under expected narratives, the people who do what is right even if they’ll never be remembered for it.

We never did find Mr. Richter’s first name, only a hopeless march of people trying to save themselves. But that afternoon we slowed down and read the names, one at a time, our own homage to their existence, and to his.

I’ve been a caregiver almost my whole life, ever since my younger sister was born when I was four years old. Sometimes it’s hard to disentangle my current burnout and exhausted weariness with doing what needs to be done, year in and year out, from the aspects of a life like mine that I actually like, that are actually me—the laundry, making dinner, doing dishes, unclogging the sink, navigating math homework and dentist appointments, making dinner again, doing dishes again day after day after day after day, checking for fevers and mental health issues, soothing bruised hearts, updating the shared Google calendar, trying to serve my community and my world in the most effective ways possible. And trying to remember that there’s a sense of self somewhere in all of it. Or that I have two paying jobs.

Doing these things while looking candidly at a world that has barely made room for women to ever be anything else, anything but caregivers and the property of others, and to keep adding fight for a better future to the list year after year, decade after decade, century after century. Wondering how many people watching how many moonrises, walking alone in Moon’s light in the dark hours of the night, have had the same worries.

It’s a question churning through all those years, about where the caring, where all the making and mending, fit in the fight. I’ve wondered this ever since I became a mother. Because all of it still needs to be done. The children need feeding, the seeds need sowing, the wild needs tending, it all still needs to happen year in and year out among the shifting front lines of a too-often violent world.

The smells in my kitchen during harvest ground me somehow, starting with that first pot of cold borscht in August, which is when my personal year begins. The deep red jars of chokecherry jelly and brighter ones of seedless raspberry on the shelf, the bright snap of pickles crowding the refrigerator, made frantically one afternoon with the last of the (extremely oversized) cucumbers from the garden—those remind me of the value of all this work. The smell of sweetgrass on my hands as I twist braids and think of whom to give them to—whose hands will receive these braids, this sweetness?—the lingering stains of potato dirt and peeled beets around my fingernails.

I think of Hugh Grimes and Mr. Richter, of how their actions were a kind of husbanding and preserving of people’s lives. I think of my Russian grandmother, hoeing potatoes and beets while under evacuation during the Siege of Leningrad, keeping her children alive through bleeding hands and foraged mushrooms. Of how many ways there are to give care and tend to life.

I’m behind on a lot of the gathering and storing activities that usually absorb me at this time of year.

But my kitchen still smells of sweetgrass and warm apples, of beeswax and coconut oil from the jar of homemade lotion cooling from the stove, of cinnamon from the batch of granola I just pulled from the oven.

It smells of care and of life, of the kind of preservation of one’s self and one’s people that humans have done since time out of mind, in good times and bad. It smells of everything inherent in the struggle to create lives that feel safe in a world that isn’t.

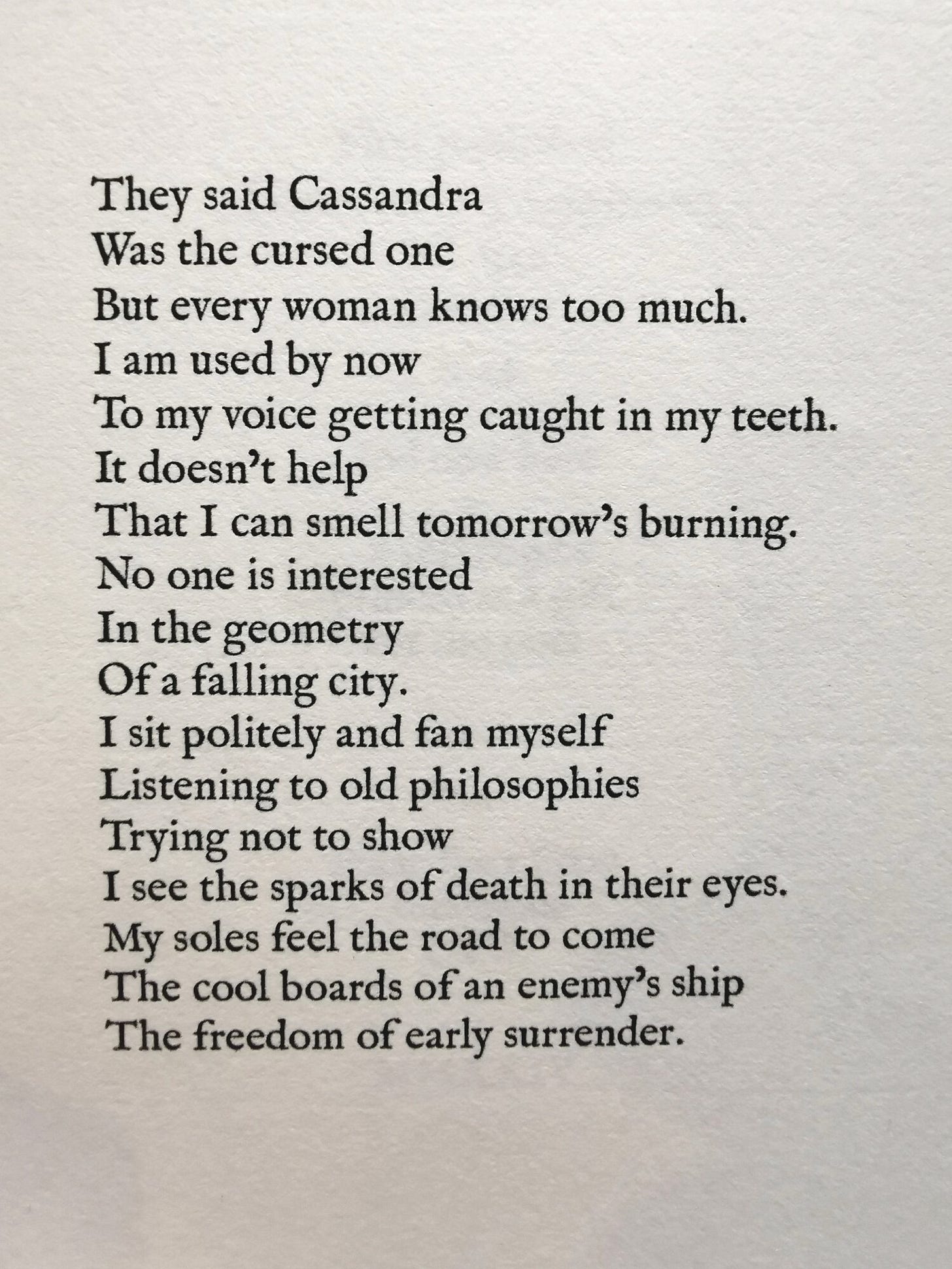

A poem here by Irina Dumitrescu, titled “Criseyde” and shared by writer and former glaciologist Sarah Boon, whose fantastic book Meltdown: The Making and Breaking of a Field Scientist is available for pre-order.

That is so beautiful, poignant and somber. I hardly got any apples from my trees this year. Maybe they are saving their energy for next year. I have missed your writing. Like you I am worn out right now. Just finding my way in this weird world.

I love your essays around this season Nia. The harvesting and preserving is something I long for. Because of subtropical climate, the part of India I live in rarely gets cold enough for preservation of food. Although there is always fresh yield in markets, I often imagine what it would be like if there wasn’t and we had to preserve food for another winter.

Here’s to the sweetgrass, apples, cinnamon, jams, and ancestors who taught us how to live through hard times, exhausting daily chores, endless caregiving responsibilities and yet be capable of extending love, support, and kinship to the world which constantly is in demand of them. And here’s to our beloved moon and women who stand in her light, howling her songs of joy and sorrow to let her sisters know that they aren’t alone.