If you’re new here, welcome to On the Commons.

Here, we explore questions as varied (but related) as: Why are 3 little-known 15th-century papal bulls still being weaponized against Indigenous sovereignty today? How is the right to forage for food related to the Magna Carta, and freedom?

✔️ Join a community of 6,600+ On the Commons readers. Upgrade here.

Blackfeet ECO Knowledge, founded and directed by Tyson Running Wolf “to increase and promote community access to critically needed methods of promoting language, culture, ceremony, history, and Indigenous traditional knowledge sharing,” will receive 5% of On the Commons paid subscription revenue from now until the end of March. (Accountability: this page shows receipt of revenue return from each quarter.)

Audio version:

Over half a lifetime ago, I was walking with some friends along the harbor road of Ephesus, once an embattled, storied, and thriving city of Ionia (and then Greece and then Rome and various lesser-known empires in between and after), and now an archaeological ruin in Turkey with just enough intact or restored architecture to hold our then-20-year-old selves in awe.

The harbor road, we were told, had once ended at the sea, which was now miles away after thousands of years of change and silt. We walked along the broad, flat stones and one of my friends said, “3,000 years ago, people were walking this same road, flirting with each other. Can you picture them?”

I’ve been picturing them ever since—people, just like you and me, full of hopes and heartaches, their particles sifted amongst the harbor’s silt for thousands of years, even their names forgotten for generations beyond anyone’s count. Someone worried over their child’s illness, another holding back tears at the cruelty of a former lover.

I’ve been working on an essay about the unholy marriage of power and wealth. I keep stalling on finishing it because every day brings another example that leaves me wondering: isn’t it obvious now? How wealth buys power and they feed off of each other? To write about Alexei Navalny’s long and eventually ill-fated battle against oligarchs and corruption in modern Russia, or the sacrifice of 18th-century Poland by prosperous nobles who cared mostly for their own comfort and position, or countless other instances of the ruin brought by unchecked wealth and its hold over unchecked power, feels . . . well, yes, obvious.

I could write for years about the compounded injustices and cumulative wealth inequality engendered by private land ownership alone—and in fact have been writing about it for years—but to find something different to say about it when the results are playing out not just in the daily news cycle, but almost the hourly, feels a bit like trying to hang onto a soap bubble.

While I try to find ways to keep that soap bubble intact—describing its shimmers and form without popping it into nonexistence—I’m going to republish a revised version of a related essay on wealth and entitlement (the psychological kind) in a few days.

Over the last couple weeks, as I kept asking myself how to bring some more foundational purpose to that essay on power and wealth, I took a break and started some vegetable seeds for this year’s garden.

I don’t usually start seeds. I don’t have a greenhouse, my kitchen isn’t generally warm enough even for fermenting sauerkraut, and it’s usually so overcast in winter here that there’s barely enough sunlight to keep a spider plant alive. But my brother-in-law gave me an old grow light to try to keep a medicinal tobacco plant growing over the winter (it did! it’s small but still living! the aphids love it) so I thought I might as well try to get a start on the garden, since where I am in Montana we don’t get enough warm summer days most years to coax a tomato plant from seed outside, much less pumpkins or melons.

Sorting through my box of seeds turned out to be one of the most hope-generating things I’ve done in a long time. I don’t know why. I wasn’t thinking about “well, life goes on” or “no matter what, people still need to eat.” It was the seeds themselves, like they were wrapping little tendrils of magic light around my fingers as I tried to figure out what I’d need to buy and what I had too much of. They took me completely out of myself and the most recent text threads of news from family and friends. Life. No narration or clever turns of phrase, just a few moments of life, of feeling alive and part of it all.

It felt really good.

Some days later, I was driving toward home and a truck with the U.S. Forest Service logo stamped on the side—not an uncommon sight where I live, among well over a million acres of wilderness and non-wilderness land overseen by the USFS—turned through an intersection in front of me and I started crying.

Among the insanity of what’s going in the U.S.’s ongoing hostile corporate takeover of a government, the professions and lives wrecked and overturned, and uncertainty and fear of Forest Service and many other employees, the goal of selling off and profiting from public lands is clear. It was an aim in 2017 and remains one. It’s why I wrote an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times about the commons and the kind of freedom held in public lands in 2019.

All land “owned,” public or private, has in fact been stolen, and it can be stolen over and over and over again. As I wrote shortly before the 2024 U.S. presidential election of my relatives in Russia, “Nobody in my family takes democratic freedoms for granted, but perhaps it takes living under dictatorship or oppression to realize that even the right to fight for something better can be stripped away.”

Which is just as true of nature, of the more-than-human world, of clean water and freedom to roam, of foraging for huckleberries and sleeping by wild rivers, as it is of the right to protest and to vote. This week I am going once again to my favorite Forest Service cabin, and wonder now if it might be for the last time, if I might never again be able to walk into the freezing waters of one of the only free-flowing and minimally polluted rivers on this continent, might never again listen to the packrats thumping around at night.

The day after I cried at the sight of a Forest Service truck, for all my friends and acquaintances who had lost their jobs or were worried about losing them, for the lands and waters that gift us so much, I gave a talk to an audience largely composed of public lands and wilderness advocates.

The talk was half about walking and evolutionary biology, and half about the commons, the stark injustice of privately owned land, and the vital role that public lands play in ensuring freedom. (It was recorded; I’ll post a link to the recording when it’s available.)

It felt right to give that talk, to say what I thought needed saying, but it also felt like a bit of mustering before a battle, when few besides those in the room knew what was to come, or how to prepare for it.

The residents of Ephesus lived and died, planted seeds and fought for what they loved, for over a thousand years. The city was ruled by tyrants and overtaken by emperors eager for land, spoils, and subjects, including Alexander the Great and later, at various periods, as part of the Ottoman Empire.

They are forgotten, almost every single one of those people. Every seed they planted, every hand that worked a chink into the Library of Celsus or wrapped a cloth around a newborn baby. Every bit of laughter echoing along the harbor road, every flirtatious side-glance and jealous narrowing of the eyes. “History” wants to leave us only with Mithridates, king of Pontus, not the 80,000 Roman citizens throughout Asia he ordered murdered. It wants us to to credit the emperor Titus with building the Colosseum, not the tens of thousands of Jewish slaves who were forced to do the actual work.

Most people who have ever lived are forgotten.

So will I be forgotten, and almost every single one of us. But how we treat one another, and the stands we take against injustice, and for a better world, still matter.

The past few nights I’ve watched the thinnest slivers of Moon low, and on subsequent nights higher, in the western sky, and thought about where my particles will be, what soil I’ll have been fortunate enough to fertilize, in a few thousand years when other eyes are watching that same Moon, Venus low and bright nearby, perhaps kept awake by a lover’s betrayal, a child’s worrisome cough, next month’s bills, or the battle of eons against the power of tyrants whose wealth has made them seem unstoppable.

History might be written around the names of those who destroy, and take credit for others’ labor, but it is lived, lost, and sometimes won by the rest of us. Those who plant seeds of all kinds, who nurture and care. In truth, history is never fully won or lost. It is a living record, the concerns and tasks that wend through our days, the neverending struggles for justice and against oppression. History is lived. It is life. It starts over again every time we plant something new.

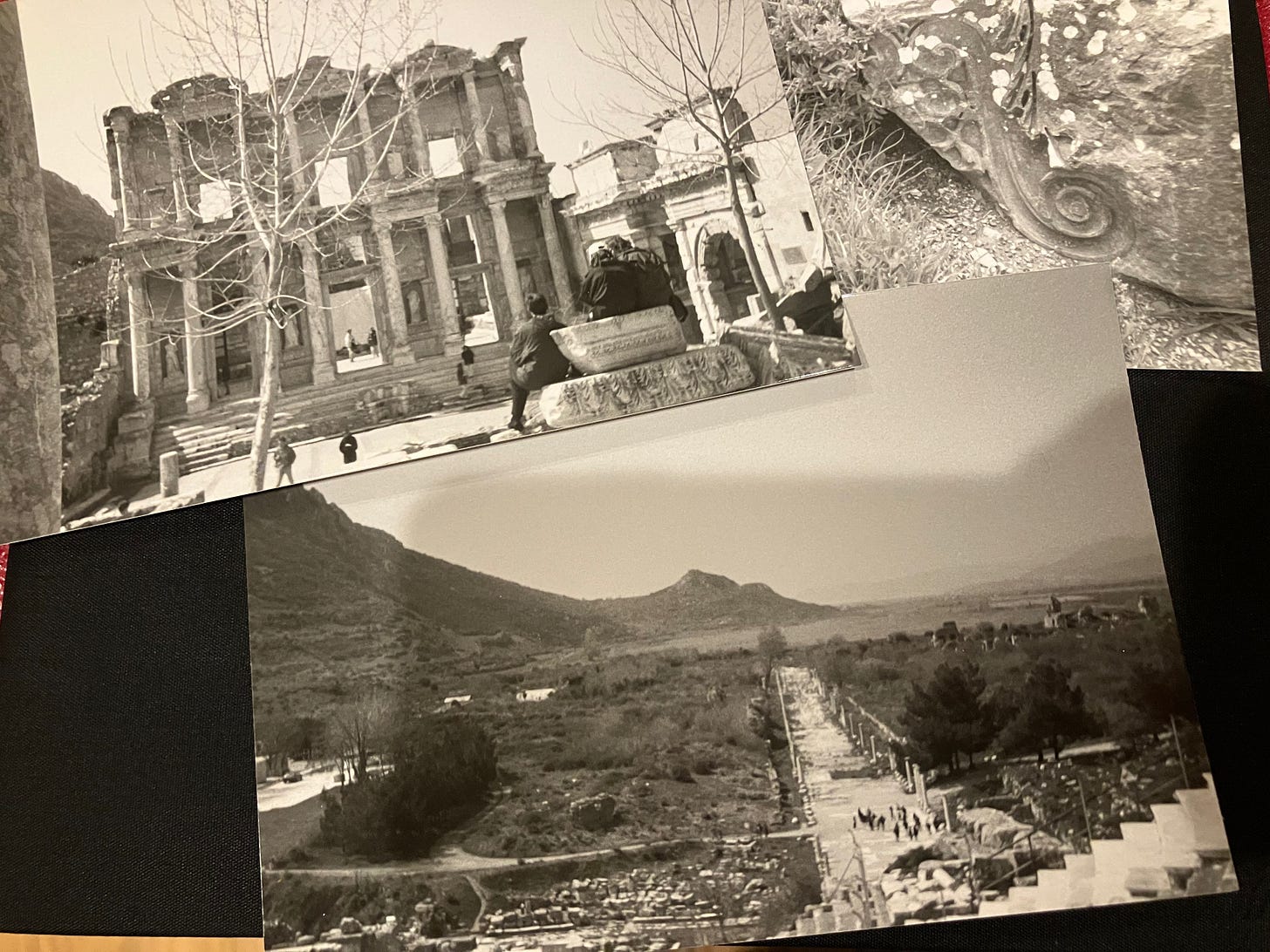

When I went to Turkey in 1997, I had a cheap little travel camera and only found out after the pictures were developed that I’d grabbed black and white film instead of color. Below is Ephesus: the Library of Celsus, a stone carving detail, and the harbor road from a vantage up in the ampitheater.

From nearby you in Saskatchewan, sending best wishes for all the seeds you plant.

Your beautiful essay and thoughts reminded me when I was a little boy (hopefully still have some of that left inside me) and I used to take old coffee cans, filled with dirt, and plants seeds and then place the cans on the window sill and behold the magic as they sprouted and grew. Strong, incredible memories of something spectacular, especially to a little boy and still spectacular to an old man ❤️