Welcome! For those new here, On the Commons explores the deep roots and ongoing consequences of private property and commodification—from the Doctrine of Discovery to ancient enclosures of the commons, and more—along with love for this world and being human in the middle of systems that often make such “being” difficult.

Book update: Apologies for the continued “wow it’s been many months since I intended to have this chapter out” delay. I have taken apart Chapter 1 of No Trespassing for the fourth time, but this time because, when I was describing my difficulties with it to a friend, she gave a piece of advice that showed me what I’d been missing. It’s finally coming together as it was meant to.

New podcast interview: “Land, democracy, identity” with UK-based Future Natures. The path from writing about walking to private property and ownership, how they each intertwine and conflict with freedom and senses of identity, and how craving for land relationship can drive both love and extremism (credits to the work of

and in this interview). This has been one of my favorite podcast listens over the past couple years, and the larger projects of Future Natures have become a go-to resource.5% of this quarter’s On the Commons revenue will be given to the Flathead Warming Center, the only low-barrier houseless shelter in my general region.

Audio version:

There’s a place I’ve been taking my family camping for nearly ten years. It’s a campground around an hour’s drive from where I live, on the far side of a reservoir whose waters hold some fond decades-old memories of lingering with boyfriends, along with a couple regrettable memories involving fire and the irresponsibility of teenagers. (The fact that nobody was hurt aside from lost eyebrows was sheer luck.)

To get to this campground, we have to drive to the far end of the reservoir and then thirty miles along a gravel forest service road. It’s a place where every summer my and my friends’ kids stuff themselves with huckleberries and spend hours in the water and nobody can access text messages or online games, much less email. For four days or so I wake up hours before everyone else and sit with coffee and the calls of Swainson’s thrushes as Sun makes his slow way up from behind mountains so tall and close they almost feel looming (isn’t that a great word? looming), but in a comforting way, like a protective uncle.

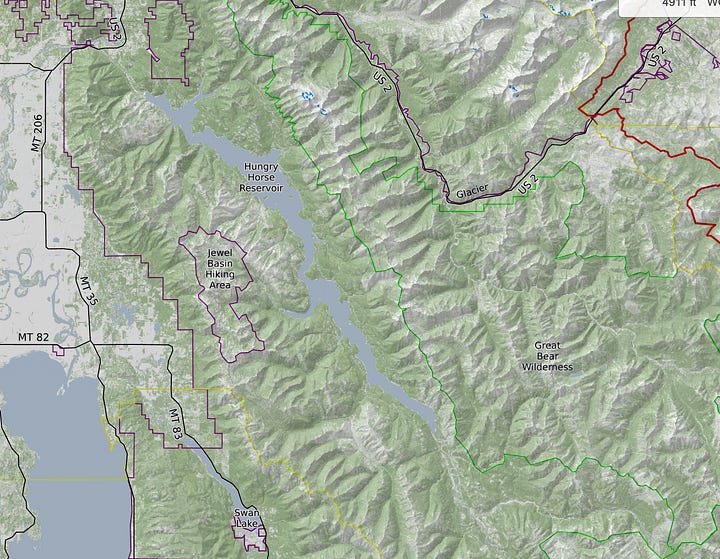

The surrounding forest backs against the Great Bear Wilderness to the east, with Glacier National Park a little ways north. When I’m there, I manually direct my brain to these facts because for some reason I’ve never been able to understand, I feel very turned around for the days I’m there, as if I don’t know where I am in the world. It’s not uncommon for me to get lost, especially when in a city and nearly always when driving somewhere for the first time, but in non-city areas I usually have a pretty good sense of place, if not direction. It’s one of the things that makes maps so delightful, being able to trace a finger along terrain or position and feel the embodied reality of one’s own self within that represented space, feel the feet tingle in the knowing of here I am. I have a hard time feeling that sense at this campground.

For years I’ve wondered if my place-confusion there might have something to do with being on a huge reservoir. When we’re on the water, paddleboarding or kayaking or just swimming, there’s an eeriness that is unrelated to my phobia of deep water. This is a drowned river, is what comes to mind as I try to ignore the growing conviction that deep-water monsters are going to pull me under.

A drowned river. It sounds nonsensical. It’s all water. But rivers have spirit and shape and purposes of their own, all of which is smothered when a dam is built to stop their flow and extract their energy.

A friend reminded me recently that I’d been meaning to look for old maps of this area from before the dam was completed in 1953, to see where the river, the South Fork of the Flathead, flowed when she was free. So earlier this week on our way north on a day of sleet, snow, and fierce wind, my younger kid and I stopped in at the forest service’s ranger station, where there turned out to be no old maps or any idea where I might find them. But it was a slow day and someone’s interest was sparked enough to spend time poking into CalTopo online for historical maps until she found what I’d been looking for.

And there she was, the South Fork, undulating through a narrow valley as mountains spilled streams and creeks into her, receiving snowmelt and rainfall as she headed down to Flathead Lake. Next to her, the modern reservoir looks less like an expansive lake we play on every summer, less like a monumental feat of engineering, and more like many technological outputs of modern humans: a little grandiose. And temporary. The reservoir is fun—and of course it’s still water, with its own voice and energy—but it doesn’t have quite the same sense of wholeness, the this-lifeness, of the river. I look at that old map and feel oddly relieved. Like I finally know where I stand.

During the Q&A session after a recent online presentation, someone asked me about the chapter titles in my book A Walking Life—nine iterations of “Stumble,” “Lurch,” “Stride,” and so on. I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me that before, and it took me a minute to remember that I had originally used similar section headings—variations on “walk” and ideas related to it—for the first essay I ever wrote on walking, years ago, for the small literary journal Lunch Ticket, titled “Wander, Lost.”

It was in that essay that I first linked freedom of movement with freedom of thought. It was also, as far as I can remember, the first time I thought of both as, tangentially, related to the movement and constraint of rivers.

“As our freedom to walk becomes ever more constrained, as air quality and housing developments and busy roads force us to spend more time in our homes and cars, we might lose even the words of movement that reflect every land-tethered animal’s most basic motion. Ramble, meander, rove, roam, wander, deviate, digress—will they slip into disuse, become arcane ideas? As we forget that they ever applied to our physical bodies, to our ability to get from here to there or from here to nowhere in particular, will our minds lose the ability to do the same? What happens to our ideas and bodies when neither can wander aimlessly, get stuck in the mud, backtrack, reconsider, keep moving until we find ourselves in a place beyond our knowledge? . . .

. . . like a river that’s been straightened and reinforced with concrete, exploding every now and then in an anger of floodwaters but never again allowed to meander. My mind has begun to feel the same.”

I think constantly about the relationship between freedom of movement and freedom of the mind. I have an unpublished essay on the subject lurking in my files that might or might not ever see the light of day, structured around the movie WALL-E, which I’ve watched about twenty times, and it came to mind again recently when reading Thomas Pluck’s novel Vyx Starts the Mythpocalypse, as Vyx’s parents are taken by the government’s Ice Men who then stalk their path as they travel the land in search of safety, running into awakened mythological beings along the way. Control of thought—including the freedom to live as our true selves—and control of movement go hand in hand.

“Wander, Lost” also provided the seeds for the sections of A Walking Life about my father’s life in the Soviet Union and the ways in which interpersonal and public trust can make or break a society, especially when it comes to government suppression of speech and protest, and how personal relationships are weaponized in its enforcement.

Trust is, like the freedom to wander, an invisible force whose degradation can make visible the erosion of liberties to those who had always thought themselves free. What one once might have thought endless and inviolable is revealed to be that which can be taken, and lost. Kind of how degradation of a river ecosystem can’t help but be reflected in the health of every single life touched by its waters.

I’ll probably never get to meet the river buried under the reservoir we camp at. Hungry Horse Dam is one of the largest in the country, and seen as essential in a network of electricity-generating hydropower dams along the Columbia River watershed. But there’s something about seeing a map of where she was, the free river, that might help orient me next time I’m up there.

At the very least, when the kids race down to the little peninsula where they watch the sunset, I can remember that while the placidity of the water is a human-made artifice, the beauty remains wild and free, and something of the river reaches up to meet that evening glow, to say the river is not gone—her stillness won’t be forever. It might be generations in the future, but she will one day find her familiar curves, playgrounds, and resting spots again, running her way through the mountains as she was meant to. Free to roam.

If we’re lucky, someday our freedom to wander, too, will be un-lost.

Gorgeous as always.

One thing about river water: the more it's constrained on either side, the faster it goes (with enormous caveats, because that principle gets overriden when there's just a massive load of water pushing behind it, eg. the Amazon, one of the fastest rivers in the world). I think about this a lot in terms of creativity - how there's a sweet spot between being reservoir-lazy and mountain-stream-super-frantic, and we're all trying to calibrate ourselves up or down onto it to find our right state of flow. Now thinking about this some more...

Have you ever traced a river from source to end? The way you write this, I feel like it would be a satisfying thing for you to write up - including if that river doesn't exist anymore, but really needs someone to write a short but deeply felt biography of it.

Regarding sense of direction, I was just listening to an old episode of Radiolab where the late Oliver Sachs admitted he carried a couple of supermagnets in his trouser pockets to aid him with his terrible self-navigation skills. He could always feel them tugging him towards Magnetic North, and said it was helpful but slightly disturbing, like his trousers were alive. (Robert Krulwich got the giggles about this.)

It's incredible how many twisting braids interlock between freedom to move, freedom of thought, the freedom of trust. I love how you follow each one with such consideration, such care. To find the river undrowned, if only on a historic map is a kind of prayer. Will be thinking long about how you so finely revealed what it is about trust and betrayal--how it is a constriction, something that was free that is revealed to be constricting in the worst ways. How beautiful though, to think of how freeing it is to our sense of self and inter-relationship with the world, when we hold trust with another.