Welcome! For those new here, On the Commons explores the ancient roots and ongoing consequences of private property and commodification—from the Doctrine of Discovery to ancient enclosures of the commons, and more—along with immersion in the offline, off-grid world, and examining the various systems that present barriers to simply being human.

I recently heard Robert Johnson say in an old recorded conversation, “The winds of the 12th century became the whirlwinds of the 20th.” It was in the context of relationship expectations and Jungian analysis, but struck me because it applies so well to theft of the commons. When it comes to land ownership, we’re all still living out the battles and injustices that led to the signing of the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest, and the centuries of rebellions against enclosure and loss of rights, 800 years and counting.

Paid subscriptions help keep On the Commons aligned with its core ethos: dismantling enclosure and refusing “No Trespassing” signs. Access to the commons—whether water, food, land, or information—is key to having a relationship with them, and with one another.

Local-to-me people: a couple of upcoming local event announcements on housing and transportation/walkability are at the bottom of this page.

Interview: has been publishing a series of Reciprocity interviews on . She kindly asked me to participate last June, and it was lovely to be part of such a generous-spirited series devoted to our relationships with all life, or what I call this-world: “I don’t really need to get any of it ‘right’; I just want to be better acquainted with the life I live among, enough to give all of these lives, from caddisflies to braided rivers to pronghorn herds to bluebirds, the respect they deserve. To relate to them as the kin they are.”

(I wrote more extensively about American Prairie, pictured here, a few years ago, including local resistance to the vast conservation project and how both are related to sticky issues of identity and entitlement, as well as how insistence on specific land uses can be tied back to the Doctrine of Discovery’s decree of ownership being a right to domination, and the foundation of America being not freedom, but land speculation and theft. The tensions discussed in that essay are perennially relevant, but especially when there is a lot of energy directed toward a major U.S. election.)

Audio version:

There’s a kind of soil in eastern Montana that anyone who lives there or is familiar with the area calls “gumbo.” I don’t know where the name came from, but my mother, who grew up on a ranch near the Big Sag in eastern Montana, has referred to it often. She’s mentioned many times how a bit of rain turns fields and dirt roads into a sticky, slippery clay that will grab your shoes, your hands, the tires of any vehicle, and make movement difficult if not impossible until the mud dries out.

Last week I called my older sister on the way back from staying at American Prairie (AP, formerly called American Prairie Reserve), where my younger kid and I had gotten unexpectedly stranded when a rainstorm came through and stuck for nearly 36 hours, flooding parts of the road that was our route out and turning it into gumbo everywhere. “Gumbo” is the result of bentonite clay coming in contact with water, expanding the clay molecules to up to 14 times their dry mass and bringing out, as AP’s website says in a dry, ironic tone to possibly anyone who’s experienced it, “the soil’s adhesive properties.”

“American Prairie Reserve Safety Manager Dan Stevenson has a fairly straightforward recommendation for dealing with gumbo: ‘Don’t be there when it occurs.’”

I heartily agree, and yet there we were.

“I don’t have much experience driving in gumbo,” I was saying to my sister as an opening to telling her about the saga of watching my kid’s and my fresh water run low and the terrifying drive out.

My sister had graduated high school in Great Falls, Montana—geographically in this general region, for those who don’t know it—and had spent more time at our grandfather’s ranch growing up than I had. She knew these roads and what happened to them in the rain. We both interrupted my story to say at the same time that nobody has much experience driving in gumbo because if you’ve done it once, you know better than to try it again.

I’ve been trying to feel my way into descriptions of that driving, which was somewhat like maneuvering a car on deep snow over slick, fragile ice, with quicksand underneath, but an accurate description eludes me, perhaps because I’m still shaken by the ordeal. I keep thinking of massage therapy training I’d done many years ago and the miraculous effect of oil on skin, how the right amount maintains a little friction but allows the movement of skin on skin, but too much is just . . . slippery.

“Slippery” is not an effect I want the tires of my car to have but that’s part of what gumbo does: glues itself to the torus of rubber and chemicals and removes all friction between the tire and the earth below.

I don’t want to say I had no choice. But my kid and I were going to run out of food and start boiling the agricultural pollution-drenched water of the Missouri River, and I didn’t know it then but another heavy rainstorm was on its way. Sometimes “choice” is simply a tentative gauging of comparative risk. Sometimes I wonder if that’s a core reality of parenthood. Much about this situation would have been different, or at least felt different, if I hadn’t been acutely aware that I was responsible for the life of another, beloved, person.

The night the storm started had been beautiful. My younger sister and her family had left that morning after two nights on the prairie. My kid missed the company of their cousins, but we pulled out embroidery thread and made friendship bracelets and grumbled at the crochet kit whose dynamics had stumped both of us.

We read books and saturated in the quiet of the prairie, the soft hoot of a great grey owl across the broad, slow Missouri. Listened for the coyote calls that kept moving location. I picked up Dan O’Brien’s Buffalo for the Broken Heart, which I’d heard of but never read and was in the pile of books stored next to the cabin puzzles. I wandered between embroidery, reading, and thinking of Chris La Tray’s recently published book of history and memoir Becoming Little Shell and stories of the Métis people—though was more specifically thinking of a video he made a year or two ago promoting a writing workshop on this very river, and his ancestors’ relationship with it, along with my own ancestors’ lives not that far away as the horse roams.

There is so much story in this land, and my heart aches when I drive along the miles of commodified agriculture and barbed wire cattle fencing that lead to American Prairie’s conservation project, where billionaires are conserving now-rare grasslands and reintroducing buffalo to the landscape that sorely needs them, as O’Brien writes about so eloquently in Buffalo for the Broken Heart, about converting his South Dakota cattle ranch to buffalo.

The air smells of sage. Northern harriers and Swainson’s hawks (I think) near-smothered the edges of fields as we drove down. Plains pricklypear cactus hide under at least two varieties of sagebrush and sneak out to grab your shoes. Moon rises over the southern hills, but if we hit a Moonless, cloud-free night, the stars are something else.

If everyone had access to starscapes like that, to seeing the sky without light pollution, humans might feel far less lonely. A night smothered in stars, the river of Milky Way galaxy as clear as the Missouri herself—it’s like all the world’s spirits have come out to dance.

We’ve been staying there for years, my younger sister’s family and mine. We know the weather risks and I try to time our visit to avoid summer’s brutal heat and June’s floods. This time, relieved that we’d avoided last-minute cancellation due to rain that veered off elsewhere, I didn’t see 36 hours of pouring rain and driving wind in the next few days.

When it came, and I was alone with my kid, I was chagrined to find myself riding the same waves of panic that had gripped me during a fierce snowstorm (an essay about that storm was published in Jabberwock Review and I republished it here earlier this year) that had cut my house off while I was pregnant with this same child, my son was two, and my spouse was away.

It startled me, trying to stay calm for my kid and mentally ration the food and water while plying the same thoughts that had plagued me nearly 14 years previously: how the relentlessness of the rain, how it kept raining, felt intentional, like there was a mind behind it. How helpless and scared I felt in the face of weather, and how much of those feelings were wrapped up in the foundational urge to protect my children.

How much, at these times, I think of mothers and parents and caregivers in war zones, generation after generation, gripped by that terror and helplessness to an even greater degree and knowing there’s an intention behind it.

As the rain came down, I went outside to watch the river turn muddy, running faster. I wondered how much higher it would get, whether the pronghorn I’d seen cross that morning would be stuck on one side for a while.

The moment I went out there, a bald eagle glided into view, whirling as he moved down along the near bank of the river. I watched him, and breathed, settled more calmly into a situation I had no way of changing.

Questions like will we run out of food? will we have to find a way to walk the 40 miles to Big Sandy? were what I’d been stuck on since taking one look outside at four that morning and knowing we weren’t leaving. Watching the eagle, the rain, the wind, the rising river and impassable road, I finally found some way to different questions. What would it take to truly, fully believe that all of this nature would look after my child? That I could trust all this life around me to help us survive?

I think a lot about trust, its shape and boundaries. How hard it can be to trust other people, depending on all kinds of circumstances and our own experiences. What it means to build trust and to lose it, what makes a person worthy of another’s trust. And the nonchalant ways in which dominant culture both takes nature’s, this-world’s, care and bounty for granted and yet doesn’t trust her at all. There would be no need for so much control if the culture trusted nature’s intelligence and knowledge.

I sat in those thoughts all day, between the macerations of panic and the two-plus-some hours my kid and I spent walking the mile and a half and back, in the pouring rain and wind, to a farmhouse on the main road to beg for the use of a landline phone to call and tell people where we were and what had happened. (The closest cell phone service is something like 30 miles away.)

And I thought of that bald eagle all day, of Earth and Sky, Moon and Sun, of why caring for my children through these situations, trapped by weather, evokes such a primal fear in me. I’ve never felt that fear when alone. I wondered about my Russian grandmother, if she felt these same anxious, helpless waves being evacuated from Leningrad with her two children in 1941 as the German army closed in for a siege, if the fear stalked her for the month-long train ride to the Ural Mountains in a railway car shared by several families with scant food. If her ancestors, and my grandfather’s, knew too well the same fear every time a violent anti-Jewish pogrom came through their shtetls, or they were once again evicted from entire countries.

Being stranded by a rainstorm couldn’t compare with what they’d been through, what people are faced with all the time, every day, inflicted by uncaring or cruel human powers. But bodily reactions don’t really care about comparisons, and the epigenetic effects of intergenerational traumas, too, are too often forgotten or dismissed. We all have to cope with what we’re faced with.

What would I need to get through this one, actually survivable, situation? Acceptance to begin with. Being angry or frustrated at the weather is a pointless folly. If it came to it, we could walk back to that farmhouse and beg for some food.

What I really wished for was other people. Not because they could rescue us or change what had happened but because the community of others, even or maybe especially in the face of fear, is humans’ most effective evolved survival strategy. Extreme individualism might work in the short term for a rare few people competing on a TV show, but it’s not a trait that has helped humanity survive and evolve, and not one that gets us through the dangers and heartbreaks that span our lives. That would be community. Solidarity. Putting energies to work for one another, not solely ourselves, that’s what has enabled our species’ most powerful problem-solving, creative endeavors, cultures, and survival. Care, not competition.

I spent much of that day silently leaning into my panic and challenging myself to find ways to accept a situation I couldn’t change. My kid and I made mint tea and did puzzles, pulled out more embroidery and read books, talked about how lucky we were to have protective walls and not be in a tent like we were during our last fiercely windy rainstorm earlier in the summer.

Eventually, we went to sleep. My body felt almost as exhausted by the panic as it is when in the wilderness working trail crew.

In the night, I woke to hear the absence of wind and water. The rain had stopped.

The air was still, and I went out to find Moon showing high again, just a thread past full. I nearly cried with relief and wished, still, for another adult to share all of this with: the fear, the relief, and the next step of figuring out how to get us out of there.

It was, in the end, harrowing. But it wasn’t, in the end, all that bad. I spent the morning tracing the worst parts of the route on foot, figuring out where I’d have to drive through a field and where to safely stop to open and close the cattle gates. Meadowlarks sang all around me, as they had been the entire time we were there.

The panic hadn’t subsided. The walking helped, though that wasn’t its point. I kept looking at the still-cloudy but intermittently sunny sky while testing the depth and stickiness of the mud underfoot, tracing out a precise route that might get our car out. Would it rain again? Should I risk it and try the drive, or risk it and stay?

Can I trust my instincts? I kept asking myself that before realizing it was the wrong question and had been all along. It wasn’t my instincts I needed; it was my judgment. I’d walked every bit of the worst part of the route and knew the ground well enough to make a decision.

There was something new-old about motherhood in this that I’m still feeling my way around, something about the side that leans into nurturing and caregiving, while finding a way to understanding the side that needs its knowledge and judgment respected and acknowledged. There was something it was telling me both about parenting, and about trusting the land, the life, this-world, to look out for us.

I could make this decision not because of an instinct or a fear, or faith, but because I was getting to know the land. Not enough to have any kind of in-depth relationship with it, the kind you build over generations of intimate knowledge, but enough at least to be able to trust what it was telling me.

And the only reason I’d been able to get to know it even a little was because I had access to it. You can’t develop relationship with land you’re forbidden to enter.

“Only by including communities in nature’s renewal can we recreate a culture that takes its cue from nature, rather than one that simply takes from it . . . Belonging is the democratic antidote to despotic ownership, and it requires active engagement with the land.”

—Wild Service: Why Nature Needs You, edited by Nick Hayes and Jon Moses

(thank you to subscriber Greg for this book!)

So I waited until I saw one solitary car crawl along the distant county road, which meant it was at least somewhat drivable, and told my kid we were packing up and driving out.

I got the car positioned at the top of the worst of it, a steep, sharp, short hill with slick mud at the bottom fronting the first cattle gate. I explained to my kid the route I would take to the far stand of sagebrush past the gate—the first firm ground I’d found. “Ready?” I asked them. They nodded and gripped a pillow. I wished I could do the same.

The mud grabbed instantly. The tires had no traction and the car slid down the hill, kept within the route only by the high banks on either side. When we stopped, shaking, in front of the sagebrush so I could go back and close the gate, I found a solid half-inch or more of gumbo caked onto the tires. I tried to scrape some of it off but felt like a cartoon character trying to pull bubble gum off a shoe. All I did was get my hands dirtier.

Following faint truck traces through the field next to a stretch of long, flat road mired in deep gumbo—obviously, someone had done this before, probably someone local smart enough to avoid the road unless it was bone-dry—I thought of a friend I’d had growing up, when I was eleven and we were living in Polson, Montana. Her dad worked for the timber company and she and her brothers learned to drive the family truck around their alfalfa field. That might be the last time I’d driven in a farm field, but what I remembered was one of her brothers hitching up his sleigh to their horses on Christmas so they could come the two miles to our home for a visit.

Our lives are made of all kinds of people, shaded and shaped by all kinds of trust, just like the paths that vary through our lives, the risks we take against the fears that control us, and the slow, million-billion-year movements of the stars overhead whose lives are just as dynamic as our own.

We closed the last cattle gate just before the turnoff from the main county road, took deep breaths of the rain-drenched sagebrush air, and barreled out the forty miles to Big Sandy, fishtailing in mud ruts left by an earlier driver or two on the steepest hills.

We talked about what we’d both learned—or would, perhaps, hopefully, learn, a lesson we’d each eventually embody—about our ability to do hard things. As we spoke, a bald eagle dropped down from a cottonwood tree and floated across our path, hunting low in a field hit suddenly by sunlight.

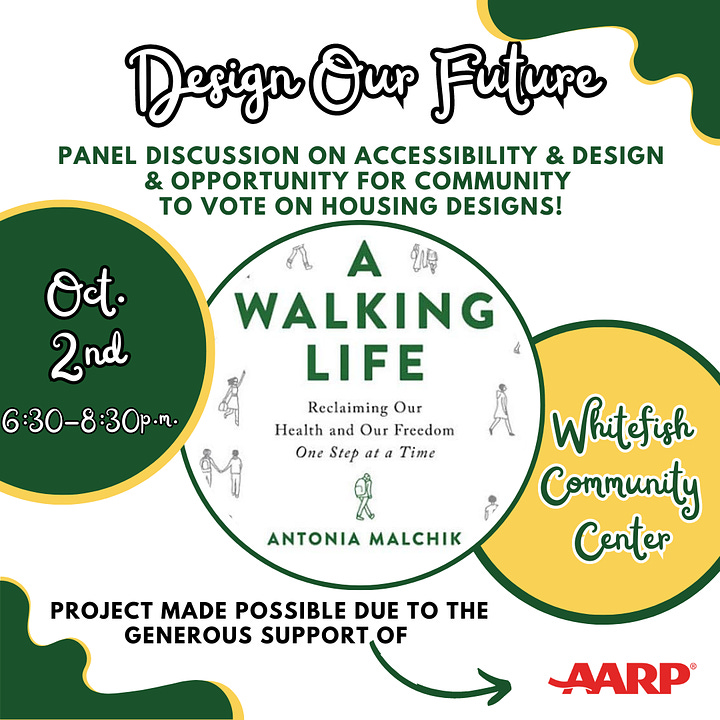

Local events October 2nd and October 8th: Flathead Valley, Montana, locals and anyone else who happens to be around! Join me for a panel discussion on affordable housing design and accessibility, hosted by ShelterWF on October 2nd. We’ll be joined by a representative from DREAM Adaptive, an incredible organization focusing on adaptive recreation. I’ve worked with DREAM on several accessibility issues around town through my work with the city’s bike & pedestrian committee and am excited to be doing this together. 6:30 p.m. at the Whitefish Community Center.

October 8th, stop by Whitefish City Hall for an open house on our developing Safe Streets for All (SS4A) Action Plan, 5:30-7:30 p.m.

I love what you’ve written here. Every time I find someone who has “long eyes” (who can see where humanity has stood for eons), I grieve for those who can only see the sliver of their own tiny lives on the ageless universe.

Perspective is everything. If you were thinking in “artistic” terms, you could see a graphic progression of thought that starts with stick figures, and ends with Michelangelo. Unfortunately, metaphors are always inadequate to reveal what “long eyes” see. When you see your own reflection, you are really looking at the entire human race. We all have more in common than we think.

"something about the side that leans into nurturing and caregiving, while finding a way to understanding the side that needs its knowledge and judgment respected and acknowledged" - the balance has always tipped for me toward the former at expense of the latter (there was no clear judgment or trust in my childhood), but lately, I've noticed it tipping back the other way. I think I'm trying to right myself. And then to add to this the trust in the land, that it will hold me. So much to be with. It feels like abundance. Thank you.